Bachelor of Fine Art, National Art School

By Hannah Vlies Lawrence

NAS likes it hard. Gone is the invocation of textile as a medium of softness. The integration of textiles in fine arts is a relatively contemporary concept. Until recently, there has been a clear division between those who craft and those who “make art”—a division bolstered by gendered, racialised, and class-based notions of value. At The Grad Show, it seems the students have developed a taste for the corruption of this domestic classic. Perhaps there is a metaphor here about the end of an era, of being a graduate. After the work is done, one craves relief but is met with hard truths.

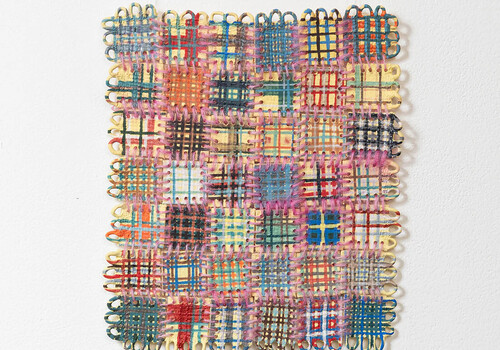

Alice Royd, Highland Fling, 2025, stained paperclay, underglaze, makeup pigment, wool, 22 x 19 cm, National Art School, Sydney. Photo: NAS

Royd knows better than most how hard it can get. Highland Fling (2025) appears to be a textile wall hanging, enlivening a certain childhood delight in even the most stoic onlooker. On closer inspection, the hanging is made from small ceramic tiles. Royd’s “textile” unravels before my eyes, hardening one tile at a time. I find comfort in the object’s solidity—a family relic protected from the dangers of moths, mould, and moisture. As wool becomes stone, Royd lets us know that we can keep it forever. I smile in thanks.

Noodle Messiter, Stretch Piece 2, 2025, emu leather, waxed polyester thread, cotton cord, metal hardware, pine frame, 51.5 x 43.5 cm, National Art School, Sydney. Photo: NAS

Where Royd has made the soft hard, Noodle Messiter makes supple scary. In Stretch Piece 2 (2025), Messiter’s silver spikes hold taut a ripped piece of emu leather that stretches partially across a wooden frame. While these features render the leather rigid and unmoving, Messiter does not shy away from the textile elements of the work. Down the centre of the leather, Messiter repairs a tear with interlacing black thread. This act of repair—of choosing to heal rather than abandon—reveals the softness beyond the work’s spiked exterior. What might strike fear at first glance, is transformed into a labour of love.

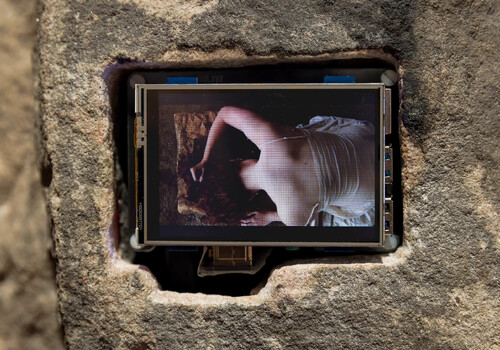

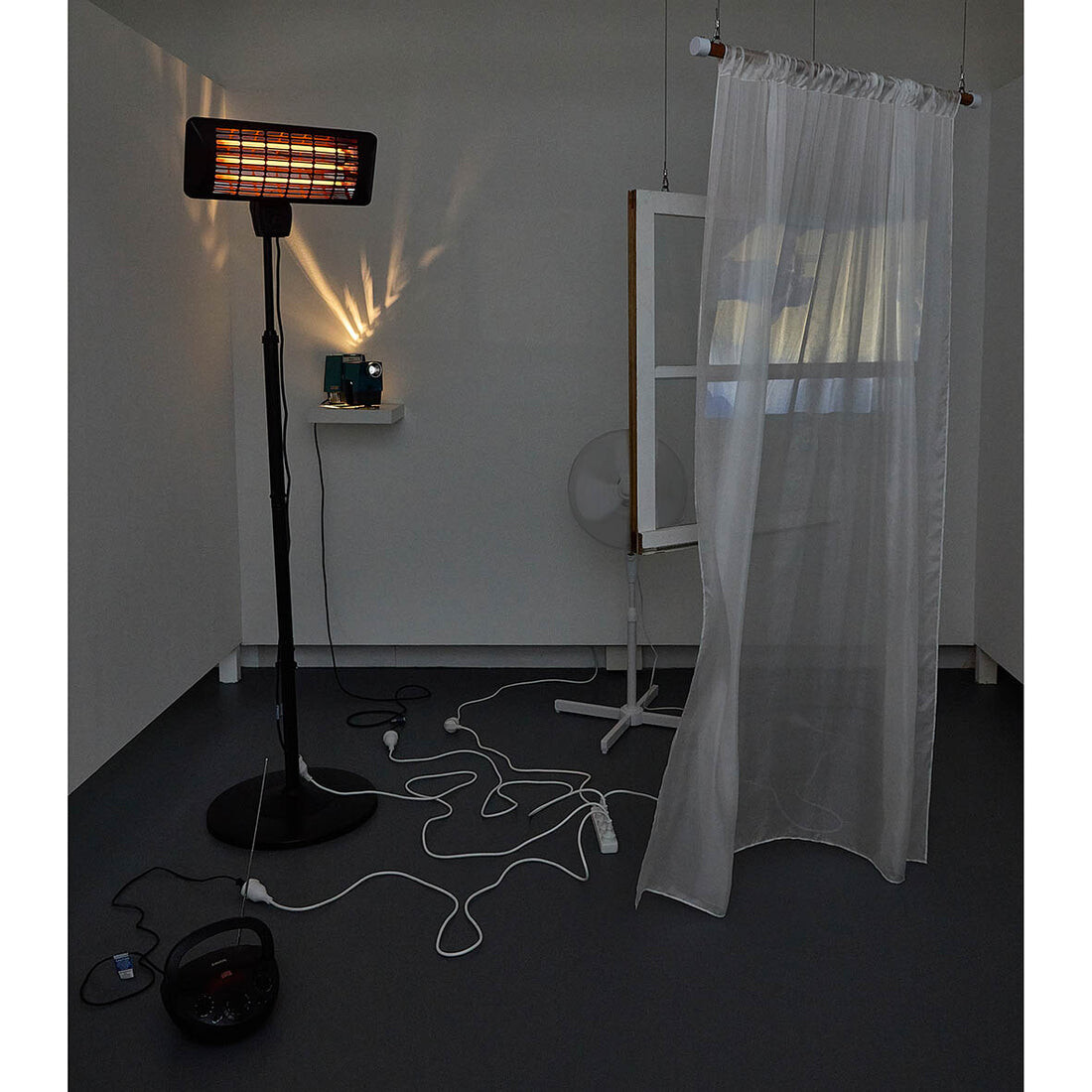

Jack Oliver Owen, Blue of My Dreams, 2025, silk curtain, hung window, 35mm slide projection, single channel audio, radio, infrared heater, fan, dimensions variable, National Art School, Sydney. Photo: NAS

Jack Oliver Owen’s Blue of my dreams (2025), is presented in the studios that butt up against Darlinghurst Road and “The Wall”, a critical site for gay intimacy, cruising, and sex work. The installation consists of an infrared heater, fan, and projector, all oriented towards a suspended window and silk curtain. A moment of queer intimacy, rendered in 35mm film, is projected through the window and onto the curtain. The image flickers between the curtain’s billowing pleats as a male figure slips in and out of focus. Then, the breeze stops and the figure disappears—the power board has shorted. It starts up with momentary verve before pausing again, stuck in a cycle of perpetual failure. I move towards the figure but am met with the searing rays of the heater. It is this piercing heat that keeps the watcher on the outside. In Owen’s words, the work becomes “a mediation of intimacy, a surface that both attracts and defers touch.” It is with this duality—this soft invitation and hard refusal—that Owen protects the privacy of this figure. Although watching from the outside, the warmth of the work emanates beyond its three walls. To experience Blue of my dreams is not to see but feel the intimacy of Owen’s constructed world. The power board shorts again and I turn, feeling its hum as I walk away.

Leaving the prospective graduates behind, I sense the tenderness behind NAS’s edge. Yet in the tussle between hard and soft, I’m glad to see graduates finding comfort in the spaces between.

Hannah Vlies Lawrence is a writer and editor living on Gadigal Country.