Bachelor of Fine Art (Honours), Monash Art, Design and Architecture

By Victoria Mathison

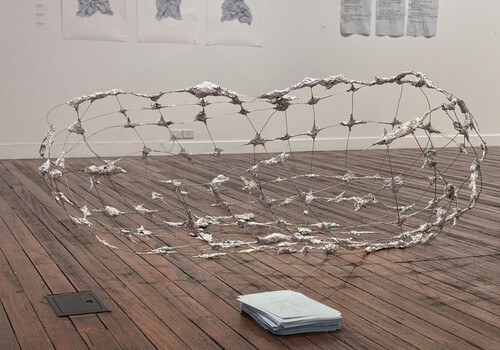

In a small antechamber; Francesca Havelock’s work, lucky charms and a tireless repetition (2025) catches me like a trick. Splitting off either side of the narrow room are a set of freestanding partition walls opposing each other and compressing the space. The walls display an algorithmic sequence of four-leaf clovers sharpened by negative space, a clear laminated seal creasing in veins across the surface. A marble sculpture lies on the floor, a double cornucopia coiling-in like an arthritic hand; while nearby a comically large horseshoe shackles a partition’s support.

Installation view of Francesca Havelock, lucky charms and a tireless repetition, 2025, MDF board, timber, wallpaper, glue, marble, dimensions variable. Monash University, Melbourne. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

Havelock’s work wryly stages the emblems of luck as both signs and simulacrums. Tokens of singular contingency are revealed, reproduced, and choreographed to the point of exhaustion. Each clover’s claim to uniqueness is overwritten by mechanical abundance. Yet a reflexive joy persists!—an involuntary quickening at the sight of so many emblems of “luck” amassed in one place. The piece suspends me happily within this contradiction, the clover’s symbolic aura is simultaneously nullified through repetition and then reanimated through sheer proliferation, as though affect continues to surge even after meaning has collapsed. Works like Havelock’s insist on a kind of sticky, speculative negotiation; the effect is to channel my attention toward the psychosocial.

Joseph Doggett-Williams’ sculpture Object Lesson (2025) delivers. A large birdhouse-like structure combines plywood, a drawer front, and a plastic extractor unit mottled with sawdust residue that suggests it was somehow instrumental in its own making, begging questions self-creation and inert, confused purpose. Circling it, I look down the glass top into its hollow body in search of withheld logic. Doggett-Williams’ Horse (2025) similarly complicates appraisal. A modern, muted yellow chair is adhered to the top of a decorative, antique wooden chair, both components discoloured and scuffed in states of tired, displaced labour. Like Object Lesson, Horse is constructed of superficially useful parts, yet in their assembly render the object functionless. Too practical to be exclusively playful, the collection of objects are spent by their beautiful, maximalist futility.

Installation view of Joseph Doggett-Williams, pictured from right to left, Object Lesson, 2025, plywood, extractor unit, drawer, glass, 125 cm x 42 cm x 46 cm; Horse, 2025, polyurethane foam, steel, timber stool, chain, 94 cm x 59.5 cm x 52 cm. Monash University, Mebourne. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

Contrary to Doggett–Williams’ debris chimeras, Janae Hunter executes a reciprocal gesture. The installation Ribs (2025) aggregates ten wooden bed slats placed equidistantly across the floor, the final lath slightly bowed. Two hung works at the end of the room, Pillows (2025), resolve the construction of an implied bed aligned in perfect feng shui. Striped jacquard sheeting is stretched across two pillowcase-sized wooden frames, straining taught over crude edges. A loose thread adheres to the side of one, while a smear of ochre-pink make-up blemishes the corner of the other. I want to be able to picture my foundation-dirty cheek lolling across the pillowcase, but this image is made strange by its slab-like geometry—the actual impression feels closer to the sensation of my face pressed up to the plate of a photocopier, the flesh of my cheek pooling against the glass.

Installation view of Janae Hunter, Ribs, 2025, timber, dimensions variable; Pillows, 2025, cotton sheeting, wood, zinc plated tacks, eyeshadow, 48 cm x 74 cm each. Monash University, Melbourne. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

Hunter surgically splays the bed, with the works reading like an index—or diagram, dissecting, naming, and invoking the absent body as the sum of its parts. An empty, discarded wine glass languishes on the windowsill, becoming a minor relic, while Ben Sendy-Smithers’ pre-recorded broadcast of Monash donors bleeds into the space—”…Muscular Dystrophy Australia…”—inciting further conceptual lethargy. Hunter includes a poem—another abstraction—meditating on breath and sleep, “rhythm” and “return”. Havelock’s “repetitions” lurch back at me in the scores of near-same wooden slats and analogous twin pillows with their neat planes of interminable stripes.

The “work”—as in labour, as in exertion—is a structural feature across these installations. Patently obscured within excess (Havelock); actual work secreted behind the aesthetics of labour (Doggett-Williams); as conceptual drill (Hunter). But the work is mine; my search; my upstaged cognition; my sleeping body. I bend towards rest, towards the comfort of a simple truth. It rejects my advances. Over and over.

Victoria Mathison is a writer from Naarm/Melbourne