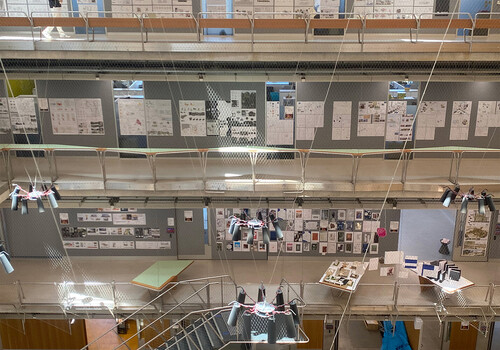

Bachelor of Fine Art (Honours), Monash Art, Design and Architecture

By Belle Beasley

The seasons are changing and I’m thinking about temperature - slow-cooking, simmering, burning to a crisp. Different temperatures produce different effects. Even minimal heat generates a shift in states. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust.

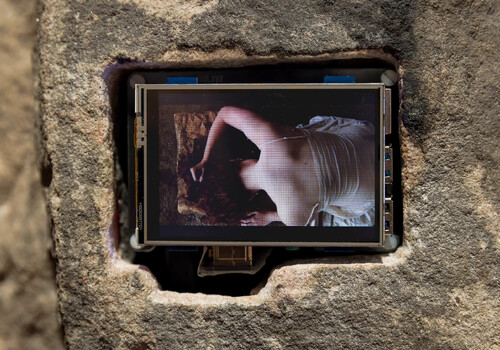

Phoebe Haig’s painting Eyes Open or Closed, Only Momentarily (2025) emanates hot white light, burning your eyes and scorching your skin. The painting depicts a cherubic face, from the philtrum to the forehead, with golden locks brushed behind ears. A searing slash of white across the eyes completely obscures facial features. The figure is blinded, and we feel their anguish.

Phoebe Haig, Eyes Open or Closed, Only Momentarily, 2025, oil on board, 115 x 85 cm. Monash University, Melbourne. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

The other two paintings in Haig’s series are also hot. Take Off (cropped) (2025) is explosive, apocalyptic: a still from the rapture. We observe the fire at a distance though; we are not touched by it. Wing Work (2025), conversely, is molten lava: a rolling, melting, morphing mass of skin or feathers, which alludes to heat on the precipice of cooling. All three works reveal Haig’s focus on “translating cropped degraded digital imagery into oil paintings”. Only Eyes Open or Closed, however, captures the dramatic violence of this translation. Like a moth to a flame, the painting is animated by the proximity to destruction that heat entails.

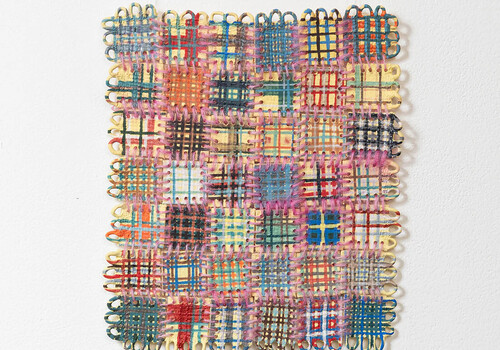

In Grace Harré’s work, the presence of heat is invoked through implied character: a certain type of girl, in a certain type of world. Something in the material and gestural qualities of the works emits a haziness, as if produced in a palo santo-charged trance. Wax is melting, sage is burning, and Harré is meditating. In Chalkboard Painting I (2025), Harré’s character is doing deep inner healing. In the darkness, serrated fab-ex (femme-ab-ex) ornamentations in pvc glue conjure childhood memories of nails on a chalkboard. Our dissociative stupor is pierced with nostalgic trauma. Rather than signalling fiery angst, this temperature speaks to chakra-aligning ego death.

Grace Harré, Chalkboard Painting I, 2025, chalkboard paint, PVA glue, soft pastel, wood panel, 183 x 240cm, Monash University Caulfield. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

In Interchange II (2025), spiritual contemplation is staged in a diagrammatic smudging of graphite and incense ash remnants, indexing the trace of temperature through materiality. Despite the painting’s gestural nonchalance, Interchange I’s field of cream, slate, and salmon pink signals the disciplined aesthetic of ‘clean girl’ culture. As if touching up concealer on a Vogue Beauty Secrets video, Harré’s meticulous interplay of blending and smudging suggests pursuit of perfection couched behind cool detachment. Where American Psycho meets shamanic ritual. Slouching towards transcendence, veiled in a smoky mist.

Grace Harré, installation image, 2025, Monash University Caulfield. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

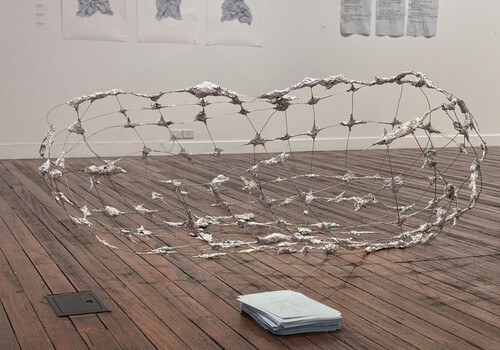

In Aliza Nickle’s large-scale panel work Wonderfilled (2025) and text-based installation rank opportunist (2025), we find the effect of a crackling campfire. The heat generated by these works is subtle. It doesn’t burn us, it rather singes. Wonderfilled is a Rauschenbergian flatbed collage comprising printed images, dollar bills, steel nails and coin-shaped forms pasted on Masonite board. Images and objects gesture nebulously to a place, time, and mode of existence: an abandoned campsite, a hoarder’s dusty basement, collectible curios. These collaged elements are at times raw and exposed, at others obscured with muddy markings. Their light flickers, offering moments of intelligibility before plunging back into the shadowy unknown.

Aliza Nickle, Wonderfilled, 2025, masonite, paper, oil stick, stainless steel, leather, one-dollar bills, brass, 250 x 850 cm, Monash University Caulfield. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

Alongside the panel work, the words rank opportunist are inscribed into a column with stoneware beads. There is no discernible connection between the two works, bar the tonal relationship of the raw amber beads to Wonderfilled’s rustic brown panelling. Side by side, the works function like a riddle: alluding to deeper meaning whilst simultaneously disclosing it, generating a question rather than answer. Clarity hides in the quivering darkness, just out of reach. Nickle’s works create a world shrouded in mystery, in which warmth generated by only the smallest embers threatens inferno.

Belle Beasley is a critic based in Naarm/Melbourne.