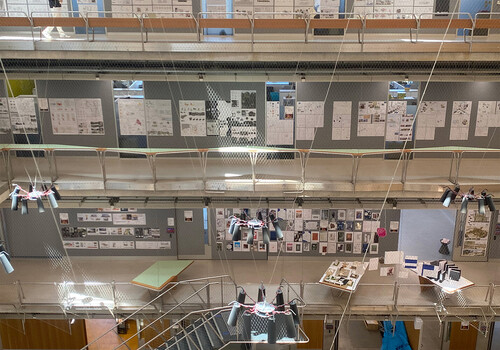

Bachelor of Fine Art, Monash Art, Design and Architecture

By Ava Lawton

I’m at the MADA Grad show on a Saturday and the studios are deserted, but I’m grateful for the solitude. It means I have space to back up, and let the blurry halftones of Lexi Picciani’s prints come into focus as a fragmented photographic image of a Classical ceiling fresco.

Lexi Picciani, Self Portrait, 2025, copper etching, ink, paper, wood, 12 prints each 22 x 19.5 x 1.9 cm, Monash University, Caulfield. Photo: Andrew Curtis

The obscured scene conjures a foggy familiarity. I might have once gazed up at this ceiling, or looked down and seen the geometric grids of moulded plaster as city streets on Google Maps. But, getting closer, it registers that this familiarity is not with the images, but how Picciani has reproduced them. They’re printed in a blown-up version of the layered CMYK dots that compose nearly every digitally-printed image we see, recreated, impressively, via copper etching. With this laborious and tactile medium, Picciani has restored visible dimensionality to the microscopic patterns that invisibly compose computer prints, centring herself and her handiwork as the imaging apparatus. Intensifying the physical structure of everyday printed images, she makes us feel every action of the regular work of looking necessary to materialise a subject in these masses of coloured dots. The materiality of her mark-making is solidified by the prints’ sturdy wooden supports, which lend them a sculptural quality; but something softer in the next room has drawn my eye.

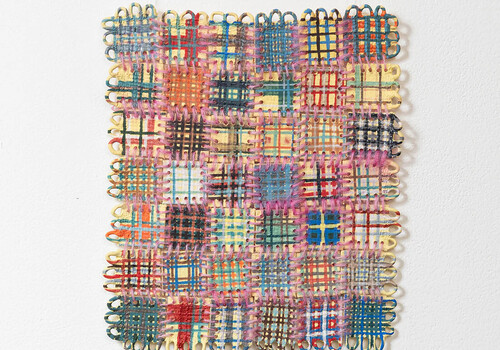

Zara Buljat, U Crvenom Vez (In Red Embroidery), 2025, mixed-media installation, embroidery on fabric, archival photograph transfer, stamped prints, dimensions variable, Monash University, Caulfield. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

If Picciani’s work induces a step back, Zara Buljat’s will make you step forward, to make out the family photographs transferred onto linen. There’s an intimacy in the asymmetrically hung, lace-trimmed pieces, like an awkward arrangement of beloved posters on the wall of a new house. What unifies the work is the repeated floral cross-stitch patterns of Buljat’s diligent, blood-red, embroidery. Her needlework becomes inseparable from the women who passed this practice down, anchoring their photographs on fabric to emphasise its connection to her cultural heritage. Stitching patterns from traditional Croation dress over their visages, she makes literal contact with relatives across time and place, her hands synchronising with the movements of theirs in creating shared symbols through shared craft. The stitches obscuring the faces of these women and children only affirms their interconnection; they all might as well be each other, or be Buljat herself. But kinship shouldn’t be mistaken for uniformity. Flanking this family album, two cloths break the repeated patterns with graceful freehand designs, assuring us this shared tradition of cultural — and self- — expression will continue through Buljat’s own practice.

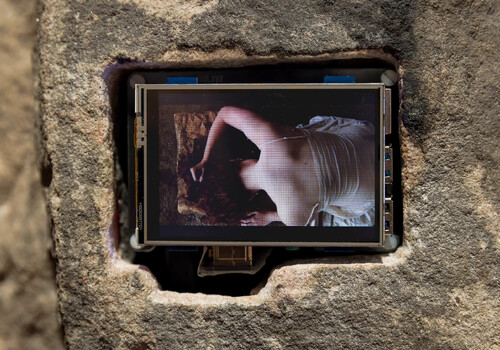

Aisha Hara, Seeds, 2025, oil on linen, 71 x 51 cm, Monash University, Caulfield. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

The “photographs” I encounter downstairs could still be dripping liquid developer. Aisha Hara’s oil paintings, a mix of delicate mark-making and airy clouds of colour, halt images in the midst of materialising. Rendered in sepia and the icy tones of film negatives, the mirages of flowers blooming (or wilting) have a beautifully unnatural glow. It’s fitting: these are not images of nature, but are their translations. Hara has captured them in development, but we cannot fully see the flora surrounding her grandparent’s home, or its preservation in their timeworn photographs she has referenced. Alongside these paintings are monoprints of Hara’s work translating her grandmother’s Tanka poetry, with single Japanese words accompanied by sets of English ones approximating their meaning. Hara’s paintings — through exposed voids of burlap canvas, crevasses of visual impossibility that her dreamlike colours and forms surround —visualise this difficult process of translating anew something so intimately, specifically, significant in its original form. Yet, simultaneously, by converting the springtime imagery of these poems into painted form, Hara has brought non-Japanese-speakers ever closer to the beauty of her grandmother’s words.

Ironically, for all this talk about photos, the ones I snapped to remember my visit to MADA are pathetic. But incorporating photographic images in their artworks, Picciani, Buljat, and Hara demonstrate the photograph’s significance isn’t solely in its visuals, but in its implementation in acts of remembrance and connection. Maybe I should post mine on Instagram.

Ava Lawton is a film programmer and emerging writer based in Naarm. She is currently an Art History Honours student at the University of Melbourne.