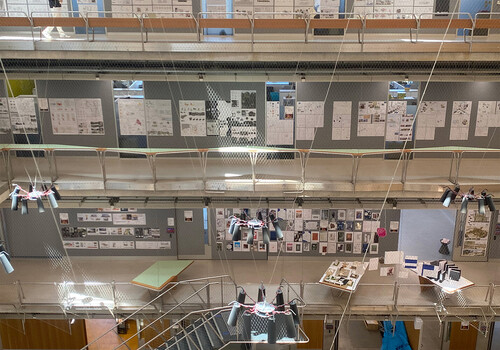

Drawing and Printmaking, Victorian College of the Arts

By Stella Eaton

I’m surrounded by the vestiges of unfamiliar landmarks. While as a Monash graduate I might have inevitably got lost at VCA, this year’s Drawing and Printmaking cohort have deliberately invited me into uncharted territory. Encountering sheet metal sculptural forms, floral genitalia prints and a beckoning soundscape, I’m at the mercy of my navigators. The works by Rosie Carr, Emma Salmon and Jya-Ruby Nation locate themselves against the confines of the natural world.

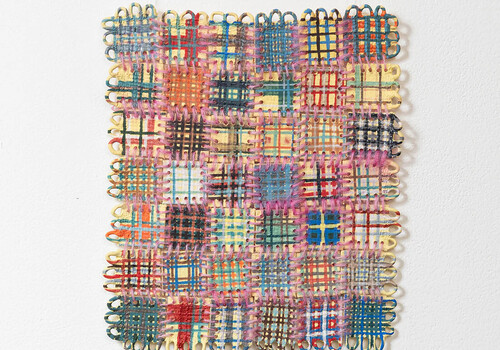

Installation view of Rosie Carr, FrangiFanny 1-11, 2025, photopolymer prints on card, resin coated plant stems, each 12x14x10cm. Image courtesy of the University of Melbourne. Photography by Astrid Mulder.

I’m first greeted by Rosie Carr’s works in the corridor, placed beyond the noise of the densely packed main rooms. Hunching over to get a closer look, I discover FrangiFanny (2025), a series of 11 photopolymer prints resting on resin-coated plant stems. These prints are the result of careful artistic intervention, created by collaging digitally sourced botanical images to evoke the appearance of genitalia. Each print has been rendered with monochromatic ink, reminding me of dutifully preserved monoprints that might be found in a botanical archive.

Before learning of the delicate process of digital manipulation behind this series, I was caught by the tender feelings I held towards these prints. While first struck by the seemingly random ability for nature to evoke corporeality, my protective feelings only increased once learning of their hybridity. Carr expands upon the conventionally yonic symbol of a flower to translate the experience of existing in between gender binaries. The plants featured in FrangiFanny are fundamentally doctored yet remain connected to naturally occurring phenomena. By placing this subject matter in a deliberate grey area, audiences are forced to reckon with this series through their own socially-encoded expectations of bodies.

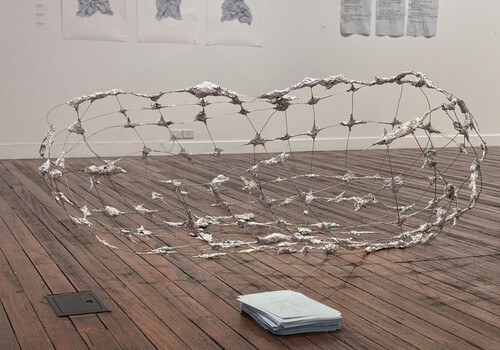

Installation view of Emma Salmon, Conduit pipework (cut through the air), 2025, monoprint and drypoint prints with rust and red oxide ink on paper, monoprint and drypoint prints with rust and red oxide ink on aluminium plates and welded steel structures, dimensions variable. Image courtesy of the University of Melbourne. Photography by Astrid Mulder.

The adjacent room is opened by Emma Salmon’s Conduit pipework (Cut through the air) (2025). Five steel sculptures with rods sprouting from aluminium printing plates wander across the room, morphing into something that resembles an artificial species of mangrove. These sculptures are accompanied by three earth-toned prints of gestural, smoky outlines on paper. This series revolves around rust and red oxide ink, printed across paper and metal with a conscious nod to the natural origins of her materials.

This work focuses on the ability for materials to preserve memories of Country, recalling Salmon’s grandfather’s experiences as an electrical linesman. Her prints resemble electric currents, visible through the erratic, coiling lines rupturing their surface. As my eyes dart between prints and sculptures, this conductive pressure feels palpable; the work crackles with a raw, kinetic energy. Salmon explains her focus on synthetic materials as a reckoning of sorts, interrogating her own distance from Country as a descendant of the Stolen Generations. Externalising this dilemma onto her materials, Salmon questions “are they too far gone to remember where they came from?”

Jya-Ruby Nation, My Branches Are My Roots, Banksia Sequence 1-72, 2025, monotype prints on paper, 2 x 4.5m. Image courtesy of the University of Melbourne. Photography by Astrid Mulder.

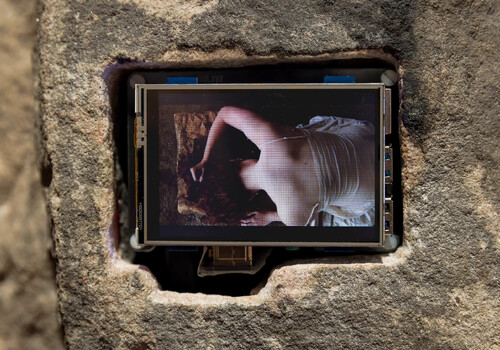

Amidst Salmon’s scorched monuments, I find Jya-Ruby Nation’s My Branches Are My Roots, Banksia Sequence (1-3) and (1-72) (2025). Three TVs are elevated, reverberating with fluid animations and a soundscape that reminds me of holding a conch shell to my ear. A grid of seventy-two non-figurative prints rises in the background, flickering between grey, black and red layers of shadow. Nation’s gently crafted soundscape acts as a unifying tool across her animations and prints. This twisting, frothing audio resonates with the life cycle of the titular banksia, introducing fire as both a destructive and regenerative tool for germination. The audio becomes a locational device, intuitively guiding me through terrain that Nation is intimately familiar with. This soundscape traces the audible seasonal variations taking place in Nation’s hometown of Mallacoota, fondly recorded in collaboration with family. Looking at the ebbs and flows of texture across these works, I feel I’m being welcomed into memories of place. These non-figurative works conjure the unpredictability of seasonal changes, mirroring what Nation describes as the embodied knowledge of Country she carries within herself.

Jya-Ruby Nation, My Branches Are My Roots, Banksia Sequence 1-3, 2025, mixed media animation, 1 minute and 51 seconds. Image courtesy of the University of Melbourne. Photography by Astrid Mulder.

These works by Rosie Carr, Emma Salmon and Jya-Ruby Nation situate themselves in delicate tension between man-made and biological structures. I can’t help but see these works as living organisms, forming a symbiotic ecosystem in their own right. Here, I find an innately human desire for belonging, unearthing the deep-rooted connection between identity and environment.

Stella Eaton (she/her) is an emerging curator and writer based in Naarm/Melbourne. As a recent graduate of the Bachelor of Art History and Curating at Monash University, Stella seeks to encourage community through ethical curation.