Honours, Victorian College of the Arts

By Danielle El-Hajj

Creative practices that engage with lived experience operate as vital forms of record-keeping, documenting history, transcribing internal thought processes and memorialising emotions. This, in turn, can influence the ways in which cultural, social and political concerns are communicated through art. Self-reflexivity can also encourage an examination of art’s function in contemporary society, including what we culturally consider to be a skilful and accomplished art practice.

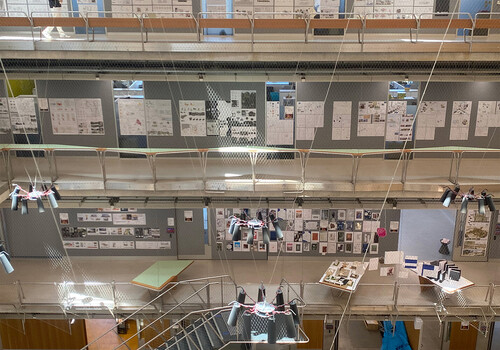

Within the confines of the stables at the Victorian College of the Arts, Kitt Falkner Babbel’s Iteration 2 grapples with the well-established question of what constitutes “good art.” Falkner Babbel’s monochromatic A5 drawings and written reflections are pinned across the white walls of a small room. Arranged in a continuous horizontal line that meets my eye level, these images depict various subject matters, including illustrations of characters, abstract forms and objects (a stationary bike features) which cumulatively present like a fusion between a reflective essay and graphic novel. Through her introspective writing process, Falkner Babbel highlights how our internal biases influence art’s (often subjective) purpose. Questions that Falker Babbel poses include: does good art develop from the environmental conditions in which we live? From our focus upon specific techniques and artistic agendas? Or, does it arise from a combination of both? Whilst Falkner Babbel does not arrive at a definitive conclusion, the authentically raw and vulnerable assessment of her own artistic practice allows us to recognise that “good art” may, as history dictates, be an ever-changing and transformative concept that continually progresses, and is shaped by the time in which it is created.

Installation view of Kitt Falkner Babbel, Iteration 2, 2025, 40 x A5 ink on paper illustrations and transcript, Victorian College of the Arts, Melbourne. Image courtesy of The University of Melbourne. Photograph credit: Kitt Falkner Babbel.

With Falkner Babbel’s inquiry in mind, I find myself sitting on a wooden bench viscerally moved by the murmuring of Arabic and English words. I stare at a simultaneously familiar and unrecognisable scene: Keiran Molaeb’s Beyt Ahle (My Parents’ House). This work is a series of four paintings modelled from photographs of his parents’ Lebanese town, with the original date of each photograph brightly embedded in the lefthand corner of each painting. Molaeb’s work is a stark reminder of a tranquil and transient place, a record of an undisturbed cultural ecology belonging to a bygone generation. It is also a memory reincarnated through the eyes of a later generation, which stands on the precipice of recognising it as home, yet also knowing that its geographical distance prevents it from being so. I stare at the paintings in a pseudo-trance, reminiscent of my own time spent in Lebanon gazing from a balcony into the far-reaching expanse of the Mediterranean Sea. Molaeb’s paintings raise important questions for me regarding cultural continuity: how can one reconcile the feeling of home via a second-hand interpretation of place? Here, the familiar and unfamiliar converge to incorporate the memories of a bygone era and the transition of those memories to the next generation.

Installation view of Keiran Molaeb, Beyt Ahle (My Parents’ House) (1-4), 2025, acrylic on wood block, Victorian College of the Arts, Melbourne. Image courtesy of The University of Melbourne. Photograph credit: Christo Crocker.

Continuing this sentiment of reckoning with one’s own cultural diaspora, Rachel Hongxun Zhou’s video work, Roots and Ruins, projects the artist’s family history on an expansive wall of the Fiona and Sidney Myer Gallery. The work includes interviews with family, photographs, identity and employment documents, as well as narration from Zhou (statements include “history is never complete”). The unrecorded and unknowable histories outside Zhou’s family archive contribute to an examination of her own cultural identity within a multicultural society, far removed from Zhou’s country of origin. Through examination of her own ancestry, Zhou creates an important dialogue between the viewer and artist, one that promotes mutual understanding and an acknowledgment of the complexities of documenting history(s).

Installation view of Rachel Hongxun Zhou, Roots and Ruins, 2025 (centre wall), video projection, Victorian College of the Arts, Melbourne. Image courtesy of The University of Melbourne. Photographic credit: Christo Crocker.

Falkner Babbel’s, Molaeb’s, and Zhou’s respective works emphasise the power of self-reflexivity. Despite the inherent biases and assumptions built within our own cultural upbringing, learning these stories about others and ourselves through art—particularly whilst living in a multicultural society—can strengthen our connections with each other and reduce biases or stereotypes. We gain new perspectives about ourselves, our place within an evolving society, and how this impacts the interpretation of our own identity in the past, present, and future.

Danielle El-Hajj is a commercial lawyer and aspiring art writer studying a Bachelor of Art History and Curating at Monash University.