Bachelor of Visual Arts, Sydney College of the Arts

By Lige Qiao

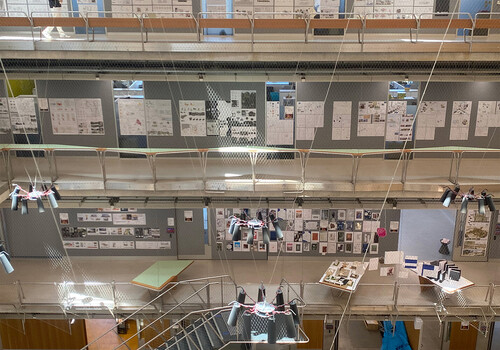

A new WeChat message pops up as I reach the Sydney College of the Arts. It’s my friend’s reply to a photo of Sydney University’s obtrusively European architecture. I’m here for SCA’s 2025 grad show. Old Teacher’s College, where SCA relocated in 2020, has just celebrated its centenary.

Image: Lily Tsuruko Tucker, DENDRITE_ARCHAEOPARTY, 2025, oak, cello rosin, steel, American ash, furniture wax, installation. Photo: Document Photography

Having attended the media preview a day ago, I walk into the main gallery with a plan. I find Lily Tsuruko Tucker’s installation DENDRITE_ARCHAEOPARTY (2025) behind a partition. Although in a corner, the sculptures aren’t tucked away like the work of other graduates with Asian surnames. All three sculptures in Tucker’s installation—an ammonite, the scroll of a cello, and an orb—are raised vertically by steel poles. Made from different hardwoods, the varnished sculptures faintly glow like taxidermy under the gallery’s warm lights. I move closer to examine each spiral, a symbol of fortune according to Tucker, but instead catch my reflection in the cold steel.

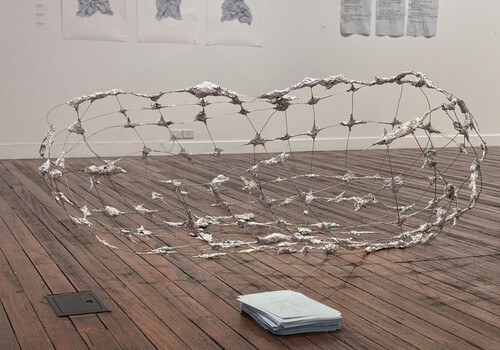

Image: Connor Chen, SADDOGHOUSE, 2025, 11 channel video and sculpture installation, 8 minutes, paint on wood, installation Photo: Document Photography

I exit the gallery as the crowds of blonde families with bouquets flood in. I walk up to the third level to see the work of two other Asian artists (apparently, their video-based works are too experimental for the main gallery). I come across Connor Chen’s work first. Chen’s SAD_DOG_HOUSE (2025) occupies a whole room, with eleven screens mounted on different surfaces: four screens on the wall to form a window, six on an elevated floor plinth to form a bed, and one “chair” at the front of the room. But the room still feels empty, as all the screens are filled with 3D-modelled objects. Everything is flattened; I am trapped by the LED screens. This is my bedroom at 2am. From Blender’s default template to a Canva floorplan, the screen fades to white. Then the eight-minute loop starts again: I see the sad dog’s house before the world disappears.

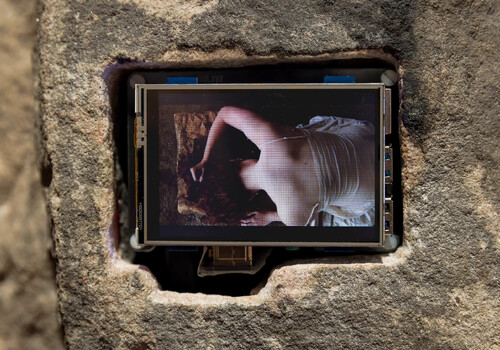

Image: Vanessa Sohn, Through Sound I Am, 2025, crt tvs, flat screens, speakers, installation Photo: Document Photography

Dr Ronald J. Burns’ portrait is mounted opposite Chen’s room. We lock eyes. The Dean of School smiles like he belongs, while I am reminded of my own foreignness. The corridor begins to feel like a maze. Luckily, the sound of hyperpop guides me towards Vanessa Sohn’s multimedia installation Through Sound I Am (2025). Electronic music jams the room, as the sound of a cassette rewinding marks the intervals. How nostalgic. I hear the artist’s voice, filtered through autotune, ask, “how far do we go?” Yes, how far? How far do we need to go to achieve a habitable corner in the creative sector of so-called Australia? How long do we need to dismantle the centre-margin-periphery hierarchy? I can just make out Sohn’s mumbled Korean words.

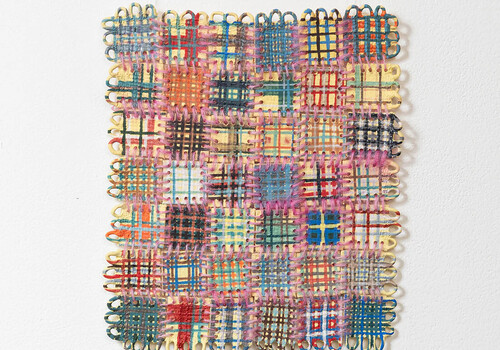

Image: Ryan Ouyang, A part of me, a part of you, 2025, mixed media, installation Photo: Document Photography

After going in circles, Ryan Ouyang’s installation A part of me, a part of you (2025) captures me. The frame, no, the doorway, is drizzled with personal, household items: a tie from an Epping high school uniform, a hand written letter, and a bowl of oranges. Ouyang’s work counters the sterile lighting of the building through a sense of play, opening up a space where the the nuances of lived experience become a spiralling symbol of courage—the courage to deviate from Euro-centric narratives and to assert agency, again and again.

Lige Qiao is a Gadigal-based artist (and curator, and writer, sometimes).