Fine Art, RMIT

By Anna Cunningham

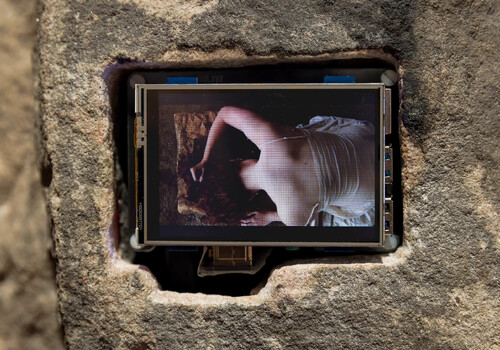

Across the RMIT graduates’ work, subjectivity is explored less as a personal confession and more as a way of finding one’s bearings. Self-positioning and disclosure operate as navigational tools for orienting oneself within the dense landscape of contemporary social and economic pressures. Isabella Rose Cort’s work in the honours cohort exemplified this sense of wayfinding. Isabella—a professionally trained ballerina—explored embodied movement on-screen alongside warped and distorted views of city-life, moving between moments of blurriness and clarity. Their work titled hush heresy heave was presented as a three-channel 14:30 minute video installation mounted on three small screens hung neatly against the wall. Each screen flickered on-and-off, occasionally joining in unison in their own fragmented choreography.

Isabella Rose Cort, hush heresy heave, 2025, 3-channel video installation, 00:14:30, dimensions variable, RMIT Graduate Exhibition. Photo: Keelan O’Hehir

Together, the videos combined sounds of conversation and ambient city noise, creating an undercurrent of clutter. hush heresy heave cut between clips of trains, grimy urine-soaked city alleyways, trams plastered with adverts of women in lingerie, 7/11, ATMs, and bug-eye-views of skyscrapers. Amid this deluge, the artist’s body spirals in response to text noting the cost-of-living crisis. A (psycho)somatic expression of nihilistic dread and capitalist overwhelm. Cort’s movement became a way of metabolising the chaos, and the screen mediated this process, enabling an externalisation of an intensely internal experience.

Moving along the honours exhibition, Idgie Kagan presented a series of ten oil paintings on canvas. What drew me to Idgie’s work was an immediate sense of innocence and naivety expressed through the subject matter. These paintings were nostalgic re-imaginings of childhood, depicting kids blowing balloons, playing piano, dress-ups, and flashing nude bums. The colour saturation was high, and contrasting, giving rise to a feeling of reverie or hazy memory.

Idgie Kagan, Protecting (left to right), 2025, oil on canvas, 61 x 51 cm, RMIT Graduate Exhibition.

Idgie Kagan, City Girl (the crying one), 2025, oil on canvas, 61 x 51 cm, RMIT Graduate Exhibition.

On a technical level, Idgie used the addition of contrasting colours for emphasis—detailing specific elements such as people and faces—to visually highlight them, while the wash of the uniform underpainting remained visible. The exposed underpainting acted as a colour-tinted lens (i.e rose coloured glasses) through which to view the subject matter, while revealing the process and structural elements that make up the painting itself, and in doing so disclosing the illusion even as the images lean into idealisation. Here painting became a strategy that both seemingly romanticises images of a childhood past and interrogates them. These paintings held nostalgia at arm’s length, and in doing so created a self-aware tension between innocence and its loss.

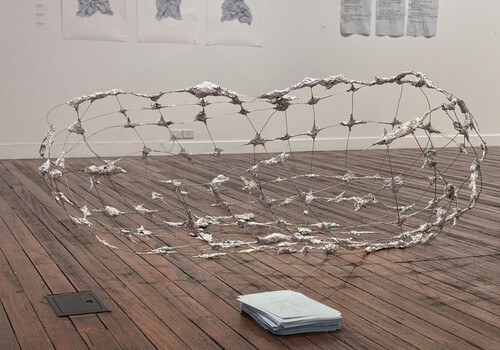

Wandering up to the masters’ studios, Olivia Lin’s work was distinctive in its self-reflexive humour. Her exhibition space was a small corner cube, which felt cluttered and cramped—as tool sheds usually do (albeit this is a mock one). Cardboard sculptures filled the floor, walls, and hung by transparent wire from the ceiling, depicting re-imagined everyday objects such as a bench, hand-saws, and hinged cardboard flags scrawled with workshop notices. A wonky asymmetrical cardboard bench—reminiscent of something out of a Mad Max set design—sat in the corner, studded with metal L-brackets and screws that appeared to be doing less of the actual structural work, but rather gave the impression of holding it all together. Lin refers to her works as “surfaces without utility;” through repurposing discarded packaging, she uses the medium to explore precarity, futility, and absurdism. The faux-functional structures enact the tool shed as a metaphor for art-making as coping, with humour and irony operating as strategies to navigate chaos while revealing the psychological impulses behind the work.

Olivia Lin, ‘Waiting’, 2025, Cardboard, Marker, gold passivated timber screws, angle brackets.

If a through-line emerges between the works of Isabella Rose Cort, Idgie Kagan, and Olivia Lin, it’s a restless grappling with the self in an attempt to navigate a complex set of internal and external forces.

Anna Cunningham is an artist based in Naarm/Melbourne, currently completing a master’s in cultural material conservation.