Bachelor of Fine Arts, Bachelor of Fine Arts (Honours), UNSW Art & Design

By Leighlyn Aguilar

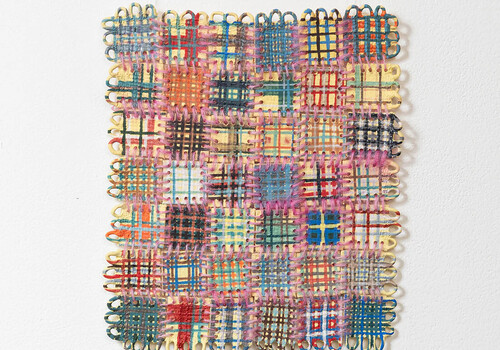

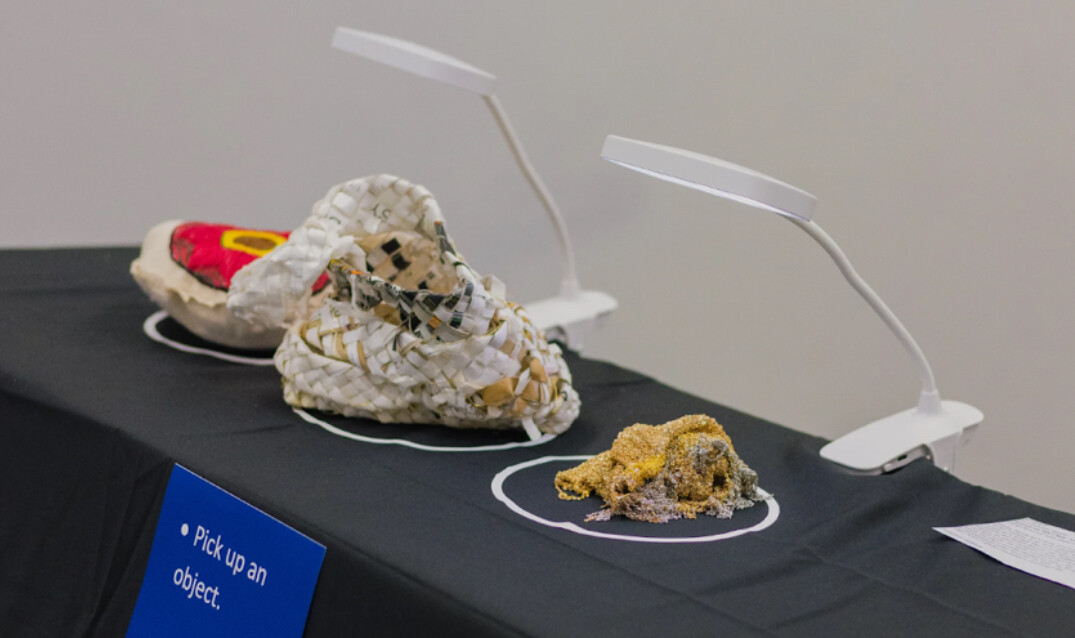

In the ominous space of UNSW’s “Black Box”, Delaram Sarjami has assembled a bittersweet tribute to Iranian and Afghani needlework. Beneath the Silk’s Skin consists of three objects: a cushion embroidered with a flower, a fragment of kilim woven not of wool but rather of metal, and an unorthodox handbag. Though braided in the manner of a traditional straw basket, it is composed of scraps—an amalgamation of daily waste threading together handwritten notes, care labels, pill packets, even chains. As I take up the invitation to hold each object, video projections come to life, showing a group of Iranian women toiling at looms. Obscured to anonymity beneath a watery filter, they practice Naqshe Khani, or pattern singing, whose lyrics serve as directions when crafting the intricate designs on Persian rugs.

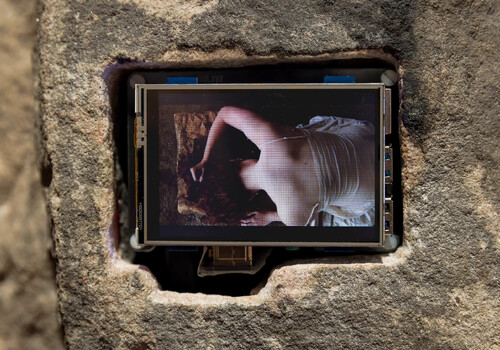

Delaram Sarjami, Beneath the Silk’s Skin (2025). Mixed media. University of New South Wales. Photo: Courtesy of Christopher Mulia.

This artistry is far from mere decoration. For Central Asian women, embroidery and carpet making is a living history able to communicate their religion, family background, and province. “The patterns I have embroidered [originate] from the regions each of my parents are from … Khorasan, Tabriz and Yazd,” says Sarjami. The cushion’s flower is an emblem of life, while the animals on the opposite face are inspired by Zoroastrian designs, recalling an ancient spirituality deeply reverent of nature.

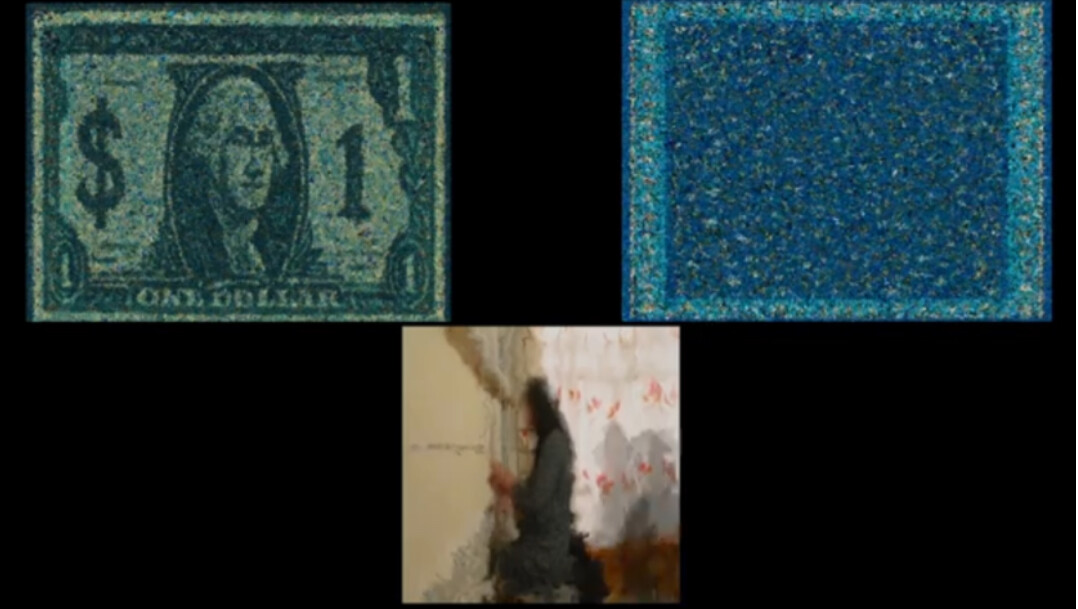

As static swallows the sounds of singing, the screen gradually takes the shape of an American dollar bill. With the greedy face of George Washington peering down at the items in my hands, I feel the sting of a Saidian outrage. After all, the bite of metal beneath my skin speaks to long, hard hours of labour; the needlework and daily scraps evidence a presence, love, and collective memory that is utterly erased by the commodifying power of market value. It is this force that renders the weaving women faceless, unacknowledged. What Sarjami’s work illustrates is a divide in value, between an East whose material culture is inextricable from the self, and a West whose satisfaction in the orient depends upon the absence of its autonomy and narrative. The attachment of a price tag demands a consumable product, not an identity.

Delaram Sarjami, Beneath the Silk’s Skin (2025). Mixed media. University of New South Wales. Photo: Courtesy of the University of New South Wales.

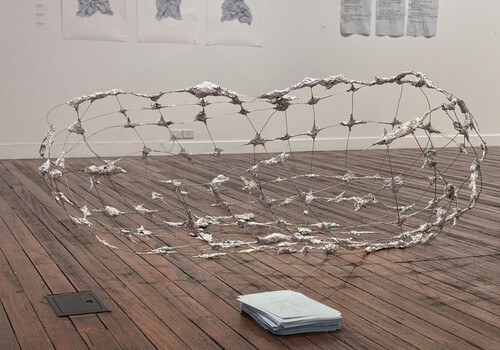

I wander next to the galleries, where Isabella Page’s a communal return carves out a small space to sit and meditate on the mundane. Here, the floor is concealed beneath an assortment of overlapping Persian carpets, the sprawl of geometric patterns dulled in areas from the press of countless visiting feet. Accompanying this, two video channels broadcast a pastiche of domestic routines. I watch someone’s back as they attend to a stove, the countertop cluttered with vegetables and appliances; a shift, and two people plod to tidy up a backyard garden. Minutes are spent brushing teeth in a Betty Boop shirt, a stuffed rabbit stares forlornly atop a desk.

Isabella Page, a communal return (2025). Moving Image with sound. University of New South Wales. Photo: Courtesy of the University of New South Wales.

It’s slow, unaffected, its images lingering beneath a soundtrack of mindless gossip and Amy Winehouse. It is a piece that worships commonplace intimacies, that demands greater attention to the beauty of the trivial and everyday. You must forgive me; I’m a sentimentalist. So I’m obliged to call upon a fragment of Omar Khayyam: “This is all that youth will give you … Be happy for this moment. This moment is your life.” Against the fast pace and constant change of working life, Page offers a room to share, to romanticise all the forgotten, forgettable instances of simple human connection. At home, the voice of Matt Berninger leaks from my laptop: “don’t let my memory dissolve.” Consider these works an ode to those beloved, overlooked rituals and routines. I’ve laid a place for you at the table. Will you be home soon?

Leighlyn Aguilar is a writer from Sydney. She has recently completed her honours thesis in Art History at the University of Sydney.