Sculpture, Victorian College of the Arts

By Amelia Scholes Gill

Faithful to his washed-up hippy persona, American artist Charles Ray loves to rehash the same hoary anecdotes throughout his lectures and writings. A favourite is to recall the “psychedelic” power of one of Anthony Caro’s first steel constructions, Early Morning (1962). He always points out that the Beatles released “I Want to Hold Your Hand” the following year. The comparison makes his nostalgia more relatable, and what he’s trying to say a bit clearer—for anyone younger than Ray, it might be difficult to imagine abstraction being new and foreign. Both works, and the movements they typify, still feel vital, but also seem to point towards something better that never arrived. Everyone is too familiar with the kind of subcultural necromancy that refuses to let go of those promises, long after it’s clear they won’t be fulfilled. 90s core, reruns of minimalism, One Battle After Another (2025), etcetera.

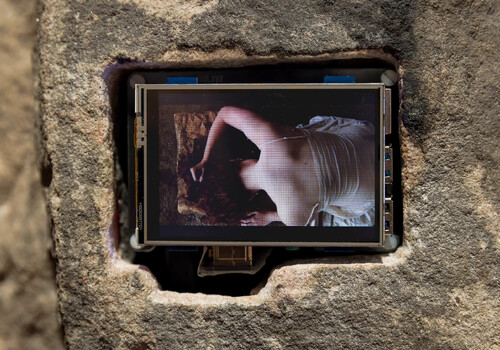

Mae Czechowski, Sex in Movies, 2025, Installation; steel, enamel, particle board, VCA, Melbourne. Image courtesy of the University of Melbourne. Photography by Christo Crocker.

Recalling at least the formal appeal of both Caro and his minimalist enemies, Mae Czechowski’s sculptures sit in poised relation to the spaces of the VCA sculpture shed, placed on pedestals or hanging with Judd-ish neatness. Each form proudly displays its precise curves and smooth surfaces, painted in matte enamel or left as bare steel. But despite this inviting quality, they also frustrate attempts at closer inspection. Some jut out uncomfortably just above head height, and the sheer length of others forces a viewer to keep their distance, or risk ruining their shape with foreshortening or the limits of one’s field of view. The installation is titled Sex in Movies, and cinema feels like an apt comparison—despite being totally excluded from a film’s action, the viewer can’t help projecting onto it, in an imposed fantasy more fun than anything they could come up with themselves.

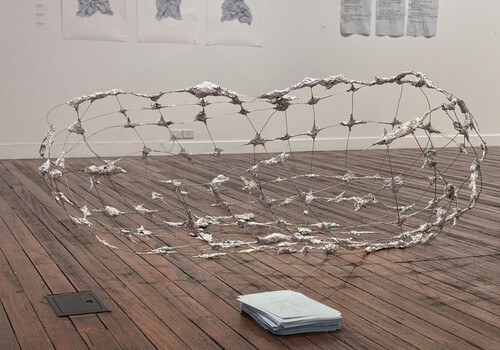

Monday Roberts, Mother Snake I Found You a Fly, 2025, Patinated bronze, glass, forton, fibreglass, VCA, Melbourne. Image courtesy of the University of Melbourne. Photo: Astrid Mulder.

Tools of enticement and seduction are a common preoccupation of the works in the sculpture department. In Monday Roberts’s Mother Snake I Found You a Fly, a crab-claw-legged coffee table attracts a cloud of bronze flies scattered on the wall like a child’s glow-in-the-dark stars. The language of domestic decoration becomes another type of natural snare. There’s still pleasure in craft, though: the flies have an intimate, handmade quality, some little more than wingless beads of metal.

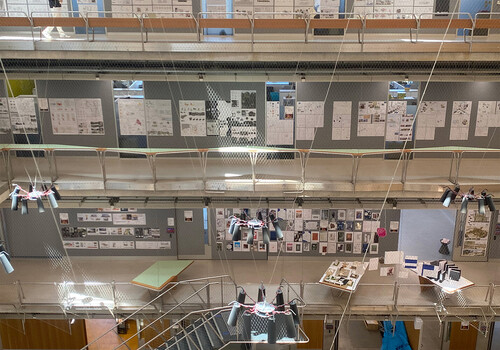

Kiki Wenzel, Booby Trap, 2025, Installation, VCA, Melbourne. Image courtesy of the University of Melbourne. Photo: Astrid Mulder.

Entering Kiki Wenzel’s Booby Trap, viewers are first met with the back of a plasterboard wall punctured with a grid of holes, some inset with metal pieces that could be spoons or teeth. Drywall dust coats the floor in a way that feels American. On the other side is something like an office, containing a large hotel-type bell and a strange pair of conjoined metal cones, in tense détente with the L-shaped wall. (1), (3), and (2) respectively. The installation’s appearance alternates between a spatial exercise and something more uncertain— (3) seems like a straightforward sculpture, but what are the fire sprinklers for? Things that seemed like formal decisions start to demand another, more paranoid look. Twenty-five of the holes are empty, and while eighteen ‘teeth’ sit amongst the dust on the other side of the wall, the remaining six are nowhere to be found. A pipe at the back rests on a cluster of fifteen nails when one or two would have been enough. Like in Czechowski’s work, something is here but withheld, evoking the feeling of looking up at a classroom drop ceiling and trying to discern a pattern in the holes and not-holes, then wondering at the adult motives that might have made them that way.

The works in the VCA sculpture shed stage their influences with an ambivalent mix of suspicion and enjoyment; even when you understand that songs from overseas and sculptures in books aren’t singing to you, they still feel good. It’d probably be dishonest to disavow the attraction of those promises—everyone still listens to the Beatles.

Amelia Gill is an artist working in Naarm/ Melbourne.