Fine Art, RMIT

By Justine Walsh

I was in a post-flu fog as I whirled through RMIT’s five-floors of grad shows. My body was still clearing out my sinuses and the phlegm in my lungs. I was drawn to the works of Fine Art Masters graduates Yongping Ren, Elizabeth M. Cole, and Lydia Lin; they were all sculptural installations that imagined internal terrains in diverse and engaging ways. As I entered the exhibition, I coughed a little and popped another lozenge, hoping to find a few breaths of refreshing air.

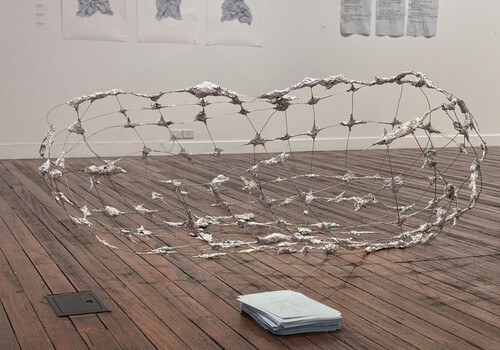

Detail of Yongping Ren, Snot Real, 2025, clay, glue, glass beads, water colour, resin, fragments, dimensions variable, RMIT, Narrm/Melbourne. Photo: Keelan O’Hehir.

Detail of Yongping Ren, Snot Real, 2025, clay, glass beads, dimensions variable, RMIT, Narrm/Melbourne. Photo: Justine Walsh.

Yongping Ren’s Snot Real (2025) was an array of resin, glass, and clay forms: some were smeared while others dripped down the wall, or were loosely bound to a pillar; some clustered on window-sills or protruded out of the walls at various heights. Presented as snot-like jewels, Ren’s prolific works showed his love for the gloopy, and emphasised the artist’s supple play with material. Don’t tell me you’ve never picked your nose and had a good look at the treasure you found. I was delighted by Snot Real. I felt like a child squishing mud between my toes, discovering the inner workings of plant stems or the vascular glow of sunlight through my own eyelids. I thought of my friend whose love of mess enchants their world, and the way they see matter shimmering with sensuality and silliness. Light trickled gently through a translucent curved piece of resin. It looked like ice caught mid-melt. The work emerged from the wall just under my eye height: a closer look reveals impressions of elaborate reliefs depicting multi-armed deities. I turned a corner and found a clay vessel like a huge piece of lotus root. Its cavities rippled like muscular intestines, or an inner-ear.

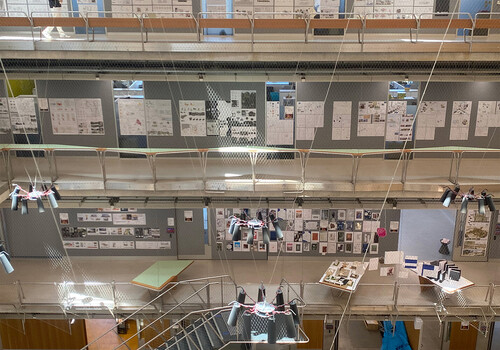

Detail of Elizabeth M. Cole, Interlude, 2025, woollen felt 3 strips 4.8 x 300 x 1500mm, square profile hand painted aluminium tube 50 x 50 x 1500mm, embedded sound system of mini digital metronomes, RMIT, Narrm/Melbourne. Photo: Astrid Mulder.

Installation view of Elizabeth M. Cole, Rendered Silent, 2025, 3D prints and plaster casts of whale ear bone specimens, hand-painted aluminium stands, acrylic display cases, dimensions variable, RMIT, Narrm/Melbourne. Background: Interlude, Rendered Corporeal, and Atlas, 2025. Photo: Astrid Mulder.

As I entered Elizabeth M. Cole’s installation, I was immediately pulled toward Interlude (2025). Here three wide loops of unbleached wool felt draped over a square-profile aluminium tube that had been painted white and transmitted regular beeps. It was suspended just above my ear-height. I realised I was measuring each work in relation to my body. A small concave piece of felt was nestled in either end of this tube, like an ear: a curve around a curve inside a curve. There was a digital metronome and speakers embedded in the tube’s interior. It felt like a way of seeking—a sonar—to find food, threats and obstructions. Marking time. Is it a countdown? Cole described her work as a response to accelerated climate change, particularly in relation to Antarctica. I stood beside the tube listening; the sound was hidden like a heartbeat. I faced the other part of Cole’s installation, Rendered Silent (2025), a pile of plaster casts of whale ear-bones on the ground, with three perspex vitrines behind them that held a single 3D-printed whale ear bone in each (along with museological tags). As my own inner ear was being tapped by the metronome’s tones in Interlude, I gazed at the mound of plaster casts. Time condenses and expands, a minute into a millennium. Though stark in tone and at times didactic, there was tenderness in these works. I found myself thinking less about the brutality of climate change-induced loss and instead recognising a love for whales and their spectres. Cole’s critique was not lost on me, but relationships emerge from coming close, and listening.

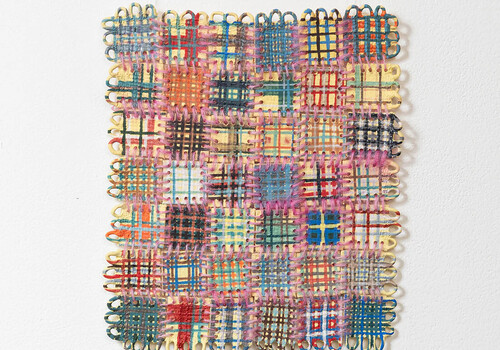

Detail of Lydia Lin, Where To Meet, 2025, magnet, iron filings, copper plate, rice paper, dimensions variable, RMIT, Narrm/Melbourne. Photo: Justine Walsh.

Detail of Lydia Lin, Where To Meet, 2025, magnet, steel sheets, iron filings, linen, dimensions variable, RMIT, Narrm/Melbourne. Photo: Justine Walsh.

Lydia Lin’s Where To Meet (2025) marked time through magnetic metal filings, rice paper, and linen. The work was about her experience of Chinese-Australian bilingual narratives and was a slow battle between magnetism and gravity. Simultaneously being pulled towards grounding here in Australia and fighting against the loss that assimilation brings, Lin’s Where To Meet caught residues loosely: the linen and rice paper became landscapes of what remained. Rice paper fibres allowed for more slippages, while the fallen filings stained the linen like mould spores. The majority of the still-clinging iron filings formed small clusters just above my eye level, facing each other from two opposing corners of the room. On one side, the magnetic filings were held with the backdrop of draping linen, while on the other they attached to a ream of partly unrolled rice paper. They pulled me in like dark portals. Their patterns convulsed and swirled as I leaned closer (or it could’ve been that a little vertigo comes with the aftermath of this flu). The simplicity of these materials and their unadorned composition, even their slightly clumsy construction and placement, led me to think of how we carry our lineages, how we relinquish, and what remains. The distance between the draping linen and unfurling rice paper is a gulf with no bridge, even though the two are almost touching. It’s a gentle grief I felt. Though the themes were deeply personal, Where To Meet was also a reminder of the immense natural forces we are all subject to, that extend into much longer stretches of time than just our lives.

I sneezed as soon as I headed back outside onto Swanston St, oh the joy of plane trees. Thank you “hayfever capital.” The bodies of work that Ren, Cole, and Lin made for their Masters of Fine Art at RMIT offered more than breathing space for me in the noisy, cluttered grad show. I felt magnetised, I was listening. I was a snotty child playing contentedly in the mud. Meandering through these artist’s works gifted me fortitude and brought curiosity, and felt like a clarifying smear of Tiger Balm to the chest.

Justine Walsh is an artist and arts worker born in Whadjuk Noongar Country and based in Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung and Bunurong/Boon Wurrung Country.