Monash Architecture, Monash Art, Design and Architecture

By Charlotte Schaller

Australia is veering wildly off course in meeting its 2030 and 2035 climate targets as policy fails to regulate fossil fuels, sprawl, and consumption. As our environments slowly decay into unliveable commercial junkyards, questions of repair, refurbishment, and politics drive much of the momentum visible in the Architecture section of MADA Now 2025.

The opulent, placeless ambition of the “iconic object” that once permeated architecture schools, with its superfluous parametric complexity, has been tossed in the recycling bin, as if it presaged the moral and economic unravelling of the post-pandemic years that followed. We can no longer make do with technical competency and aesthetic sensibilities, shuffling through styles, scripts, and trends politely detached from any ethical or social responsibility. Faced with extreme housing unaffordability, irresponsible energy use, in-motion environmental degradation, and a cutthroat workforce offering no guarantees, the architecture discipline is forced to widen its scope, demanding its modern “master builders” gain fluency across almost every frontier. These are the conditions that set the tone of contemporary architectural education and practice, and there is certainly no scarcity of critical thought in this vanguard—Monash is asking the big questions.

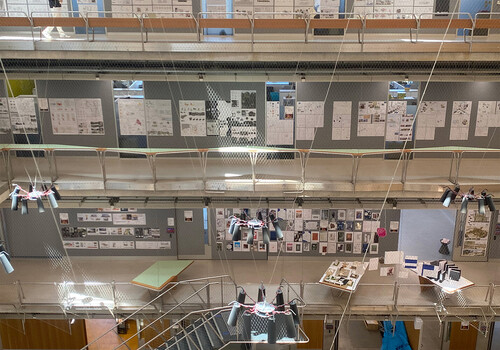

Installation view of Land (In)equalities: Retrofitting for Nature Inclusive Suburbia. Photo: John Gollings.

Facsimiles, scans, newspaper clippings, and environmental policy documents are strewn across the concrete floor of Level 3: a bureaucratic archive of decades of attempted environmental protection laid out like evidence at a crime scene. This is the installation of the Masters-level Design Studio, Land (In)equalities, led by Anna Gilby and Catherine Murphy. Architectural drawings are fixed to temporary fencing like that on a development site. A3 sheets map out suggestions as to how we might act with a little more ecological responsibility and care. These attend to place, ecologies, and surrounding environs with more intention than any of the structural or aesthetic ingredients that might typically make up a student design project.

The Design Studio turns to the seeping sprawl at the city’s edges, Melbourne’s peripheries ever-expanding in every direction. Its site in Cranbourne, on Boonwurrung Country in the south-east, has seen a wave of low-density subdivisions poured over significant ancient ecological sites in the past decade. These projects make every attempt to show how suburban design might do better by retrofitting what already exists and repairing land in response to the mess and biological fallout that is contemporary “Australia.”

Visitors are asked to “walk with care” across the scattered papers, an instruction so modest it’s almost disarming. For a society so practised in ecological irresponsibility, the simple act of slowing down and watching one’s step may already be more than many are willing to do.

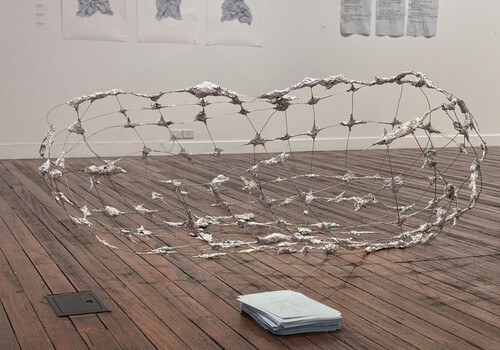

Physical models from the Design Studio Done & Undone. Photo: John Gollings

The suburbs remain a topic of concern in the Bachelor student work on display on Level 2, where students are asked to question the inherited modes of domestic living and subdivision practices. Although the consideration of “place” was often overlooked in historic suburban housing projects, their social imperatives, compartmented plans, and attention to composition, space, texture, and material are worth revisiting. As Peter Corrigan wrote in a proposed Foreword to the 1985 edition of Robin Boyd’s Australia’s Home, such houses are “not aesthetic calamities”, but ways to “nourish an imaginative world and constitute a region for the spirit.”

The Australian house, still an aspirational object for many, is shrinking, standardising, and drifting even further from essential services and community, raising the question of how our suburbs might do better to serve the spirit of their inhabitants.

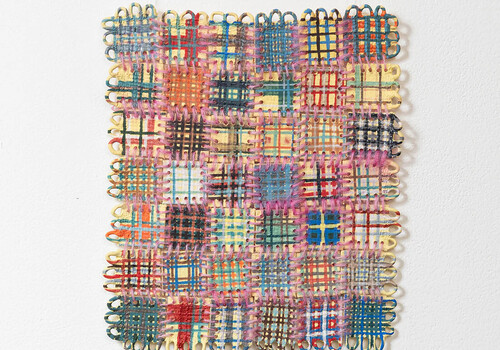

In Done & Undone, run by Eilidh Ross, a housing estate is pulled apart and reimagined as a clustered assemblage, reconfigured from a kit of parts in a so-called “Frankenstein” mode. Each coloured iteration seeks its own individuality, united by consideration of environment and context with respect to scale, landscape, materials, and profiles. The outcome is a series of models, conceived as experiments in modern living arrangements, and aimed to sway public taste away from the idealisation of the singular detached family house and towards a less formal, more flexible, and more co-operative form of living.

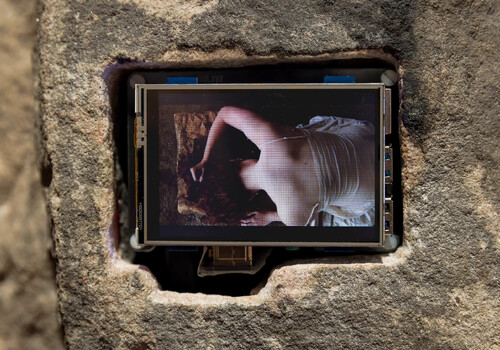

Installation view of Waterwork: Design and Make at the Quarry. Photo: John Gollings

Physical models from Waterwork: Design and Make at the Quarry. Photo: John Gollings

In a refreshing de-emphasis of fine-line drawings and renders, Monash Architecture turns instead to the return of physical models, materials, and other experimental modes of representation. Such speculative elements, often pared back elsewhere to the detriment of practice, are here given renewed importance. While a flicker of nostalgia runs through the work, individual studios assert their own flair, with a welcomed absence of any institutional “house-style” and a strong culture of “install” that has students building each exhibition themselves, giving each Design Studio the chance to curate its own scenography. These combined generate a deliberately less polished approach that is perhaps truer to the iterative nature of creative practice.

The exhibition presents a diverse suite of Design Studios that pursue a radical and ambitious understanding of what architectural education might be. It draws together First Nations ways of knowing, alternative approaches to housing, and critical judgment evident in both artefact and acts of thought. Monash has risen to the challenges facing it, learning from the past whilst addressing the future with astuteness, erudition, and clarity.

Charlotte Schaller studies Architecture at the University of Melbourne.