Bachelor of Fine Art (Honours), Monash Art, Design and Architecture

By Giulia Lallo

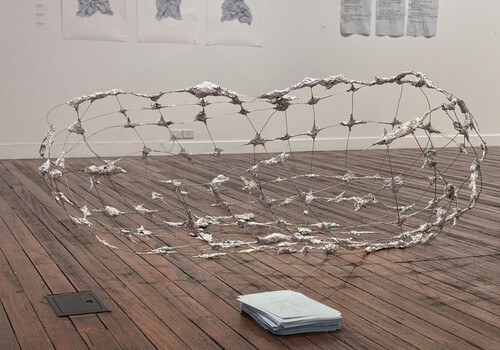

Transfixed by ancestral voices, I am ushered towards Justine Walsh’s installation Listening, Singing in the Half-Light (2025). Speakers resting on the floor sing the Irish sean nós song as Gaeilge, their cords exposed, encircling the carved limestone-cum-altar pieces. Walsh retrieved this limestone from Boandik/Bunganditj Country in a deeply engaged process with Community. Connected to the land upon which it formed, the limestone becomes a vessel to rethink colonial histories and the extractive process of mining. Walsh, reflecting on their own Irish heritage, thinks through a connection between the Irish voices that have been silenced and this Indigenous Country that continues to be desecrated. Walsh reimagines the possibilities of mining, where it becomes not a process of unethical extraction but one of unearthing forgotten histories, of resurrecting stories of stolen land and stolen voices.

Foreground: Installation view of Justine Walsh, Listening, Singing in the Half-Light, 2025, limestone from Boandik/Bunganditj Country, found light fixture, light, sub woofer, dimensions variable, Monash University, Melbourne. Background: Installation view of Phoebe Haig, Wing Work, 2025, oil on board, 100 x 115 cm, Monash University, Melbourne. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

The porous nature of the limestone too signifies how fickle and malleable these colonial histories are. Yet it is this very porosity that allows Walsh to reinscribe elided histories upon the material’s surface. Delicate as they are, there is a sense of imperfection to these incisions. They are off-centre, they lack symmetry, and their intensity varies. It is through this asymmetry, this lack of defined lines, coupled with the intangibility of the hymn-like Irish language that fills the air, that Walsh questions static and prevailing colonial histories.

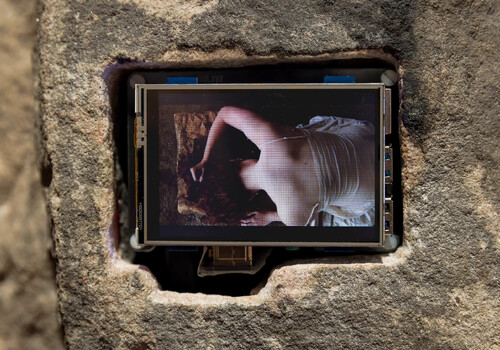

Across the gallery, Cam Ferguson’s installation As I Leave, I Look Back (2025) similarly meditates on truth, interrogating the accepted ideal of the Catholic Church as a universal moral sovereign. Ferguson disturbs the traditionally masculine domain of stained-glass window-making, interrupting a lineage of tableaux that project pious images of Christ and the Virgin Mary. Absent of this Catholic imagery and dislodged from its usual imposing place on the Cathedral wall, the stained-glass window is instead situated on the floor. It is fragmented, fractured into pieces — the excess lead left dripping and exposed. Here, Ferguson upends the intended purpose of such moralising displays: in obscuring their function, they are stripped of their authority.

Installation view of Cam Ferguson, As I Leave, I Look Back, 2025, stained-glass, photographic print, dimensions variable, Monash University, Melbourne. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

Ferguson’s Cherries — circles of red glass — also have an air of eroticism about them, stirring within their viewer a feeling of yearning — could they be glacé nipples? On viewing the adjacent photographic print Agatha (2025), itself referencing the glazed cakes eaten on the feast day of the martyred Saint, I cannot help but think of the painting Gabrielle d’Estrées and Her Sister in the Bath (1595, artist unknown). It is apparent in this juxtaposition that queer identities and longing have historically existed within Catholicism. Like the stained-glass that is moulded, like the sugary taffy that is stretched, Ferguson manipulates history to carve out a uniquely queer space.

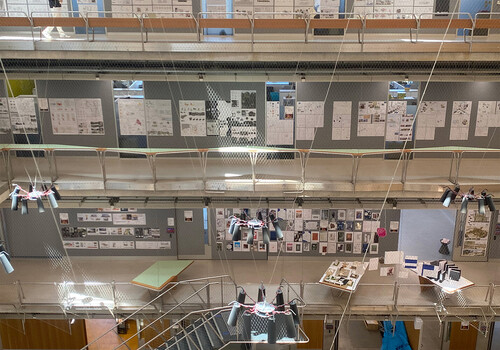

As the procession continues down the “nave” of MADA Gallery, Meg Kelso’s Things That Were Light (2025) unearths itself. The installation consists of three flat, pearlescent supports rippling across the floor, scattered with amorphous glass-blown objects that dance atop its surface. Like contemplating a pebbled garden, like finding a rock in the riverbank, a quiet Zen washes over me. Yet, beyond its seeming perfection, its evocation of calm and tranquillity, there is a violence, a rupture held at bay, conjuring ecological destruction and degradation. Rather than being fragile, the support is in fact cold, hard concrete. The glass spheres too remain open, fractured. They are not solid, but hollow.

Installation view of Meg Kelso, Things That Were Light, 2025, blown glass, reclaimed glass frit, kiln sand, ash, cement sheets, dimensions variable, Monash University, Melbourne. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

The promise of this Edenic garden, of nature’s eternal and inexhaustible delights, is shattered, mere illusion. Instead, the rocky terrain becomes the site of a volcanic eruption — volatile and unpredictable. Kelso is there on the fault line, cautioning onlookers to confront their complacency in systems of environmental harm. As for Walsh and Ferguson, there is a unanimous desire to rupture linear and static histories.

Inertia is abandoned. Everything is in flux. Memory and time flow in and out as the pebbles bob beneath the water’s current.

Giulia Lallo is a writer and emerging curator from Naarm.