Honours, Monash Art, Design and Architecture

By Wawe Ransfield

There is a horror in the near-far hometown, an eerie familiarity that comes from an intimate attachment to place, memory, and belonging. Across different degrees of narrative framing, material use, and stated influence, Mac Conley, Casey Nicholls-Bull, and Maddison Wandel find a shared rhythm in their evocation of hometown horror.

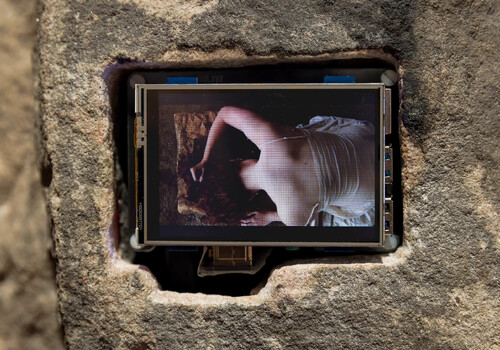

Madison Wandel, Stutter 1-4, 2025. Installation view. Courtesy of the artist. Photography by Andrew Curtis

The room preceding Maddison Wandel’s is cathedral-like; tall ceilings and wide windows and concrete floors that amplify each footstep. Stepping into the dim, windowless, carpeted space next door was akin to a sensory deprivation tank. The fresh carpet absorbed sound and light with a ravenous efficiency. Leant against the far wall, a triptych of photographs unfolds as a brief cinematic sequence: a woman running in the glare of high beams, a presumably stolen street sign in a car boot, and an almost black frame with a blown-out edge of grass. On the adjacent wall, a fourth image shows the night view through a passenger car door. Wandel’s cinematic works embed an uneasy mystery in the sparse information offered. There is no wall text, no guiding hand on how to interpret the narrative shown. While the fragmented storyboard sets a mysterious tone, it is Wandel’s use of familiar hometown iconography—aimless driving, stolen signage, the charged quiet of a night field—that produces the work’s deeper, uncanny pull. This sense of familiarity is unsettled the moment we realise that what we recognise is not our memories, but Wandel’s own personal and constructed imagery.

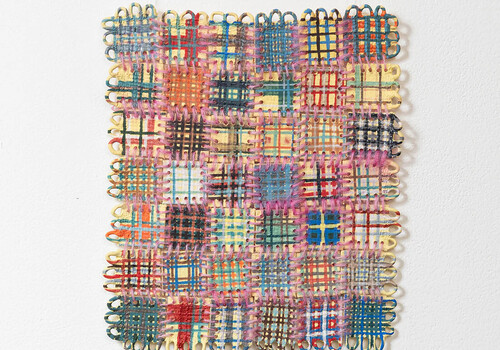

Casey Nicholls Bul, A Costume Without a Carnival, 2025. Detail view. Courtesy of the artist. Photography by Andrew Curtis

The claustrophobic environment of Wandel’s creation gives way when entering Casey Nicholls-Bull’s yellow-toned A Costume Without a Carnival. A smiling friend greets the viewer: a scarecrow figure complete with wiry grin framed with marigold sunray hair. The artist’s use of flax perfumes the space, inviting memories of harvest, old barns, and dry summers. Harlequin patterns thread the walls and a flaxen fools cap hangs poised for wear.. Certainly, the air is one of clownish performance. One pace to the right reveals the dominating work in the space: a large loom spun with flax threads and a flaccid arm distended downwards. Jars of unknown potions hang from the loom’s long threads. On the room sheet, a materials list invites further speculation with its addition of “piss, hair, wood (from my old bed frame)…” Here, Nicholls-Bull greets the viewer with a smile that only lightly obscures a foundation of abject material play.

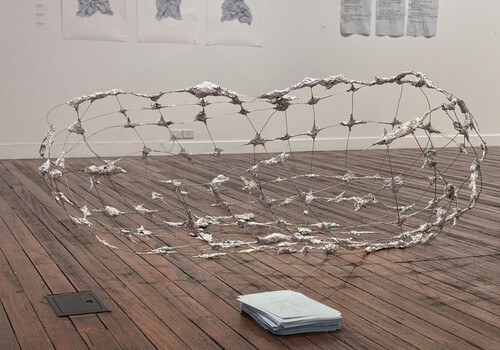

Max Conley, various untitled works, 2025. Installation view. Courtesy of the artist. Photography by Andrew Curtis

Though less narrativised than Wandel and Nicholls-Bull, Max Conley’s installation is not without its nod to home. Premising the collection on the perceptive potentials of the everyday, Conley’s recreations of the mundane features of home structures quickly reorientates weatherboards from utilitarian to sculptural. The rain catchers dotted throughout the installation articulate a sustained and patient relationship with time. A care is evident in the artist’s considered engagement with the materials at hand, wherein the selective applications of paint and curated absences of shingled tiles produce a remarkably coherent and aesthetically substantial body of work. The space itself is flooded with light- a far cry from Wandel’s and Nicholl-Bull windowless confines. To stand in Conley’s installation is to feel an environment inverted, to see the outside inside. The weatherboard claddings so evocative of the Queensland colonial landscape further queers the exhibition’s urban confines. Conley’s considered deconstruction suddenly invokes demolition and aftermath. Here the eerie emerges again, a persistent reminder to look for what is missing, hidden, or trespassing. If Nicholls-Bull is located in the Folk Horrors of Robin Hardy’s The Wicker Man (1973) and Julia Robinson’s Eerie Pageantry (City Gallery Wellington, 2023-2014), Wandel is the Suburban Gothic of Stephen King’s “house down the street”. Horror, explicit in Wandel’s installation and firmly referenced in Nicholls-Bull, finds surprisingly firm footing in Conley’s bright and open framings. Dismembered urban-scapes are at once a deconstruction of the placid suburban imaginary, and an invocation of Dorothy’s “Toto, I’ve got a feeling…”

From Aotearoa, Wawe Ransfield (Ngāti Tukorehe + Ngāti Raukawa ki te Tonga) is an Art Historian + Arts Worker interested in the demystification of contemporary art for the diverse public audience. She is currently pursuing further education, free art shows, and great fun. Mauri ora!