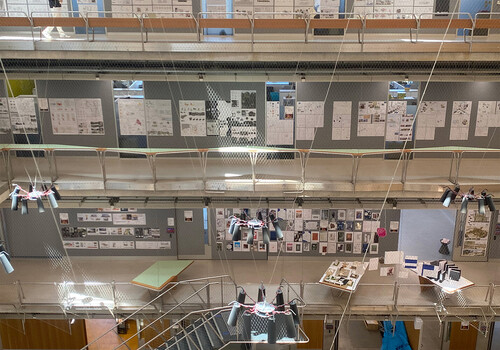

Bachelor of Visual Arts, Sydney College of the Arts

By Levent Can Kaya

Gentrification haunts Australia’s financial capital. We’re posting eulogies to Chinese Noodle House, the false idol of El Jannah is forsaken in favour of the consecrated Hawa, and fbi.radio is martyred and resurrected. On the Intro track to the collaborative noise-rap album Redbrickgothik (2023), over the menacing hum of BRACT, rapper BAYANG (tha Bushranger) whispers “This city is alive. Cancerous clump of cells on sunburnt land. Malignant tumour. Exponential growth.” Within the Gothic Revival buildings of the University of Sydney, a decadent ominousness courses through the work of SCA’s New Contemporaries.

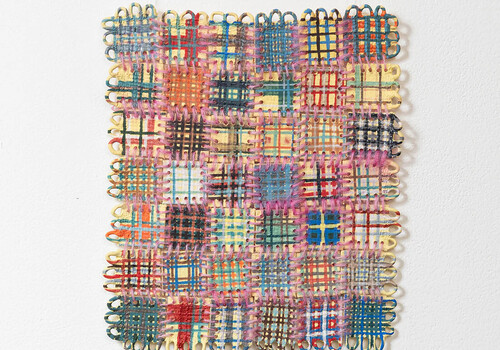

One of Kiara Steele’s hyperrealist oil paintings in god lives in Thornleigh (2025) positions us at the top of a hill. Over red terracotta-tiled roofs, blanketed by a bittersweet dusk, we look down towards a distant apartment-scape. One of those copy-paste Zetland/Rhodes/Eastgardens developments that my favourite Facebook group, Pacific Hypermodernism, describes as “Meritonesque.” Here, we’re on Thornleigh Street—a part of the city’s at times vilified bible-belt. Aptly, her vignettes of the North Shore are encased in sacral wooden frames carved to invoke liturgical structures. Miniature graff tags decorate the frames. Against religion, gentrification, DAs, and LGAs, the streets always get the last laugh.

Kiara Steele, god lives in Thornleigh, 2025, New Contemporaries, Sydney College of the Arts. Photo: Document Photography.

The other paintings in the series render decaying industrial sites and a disused, glowing, pylon sign—the sort you see driving down Parramatta “Stroad”—in the aesthetics of the sublime. Here, she nods to German Romanticism, a style which reified nationalistic fantasies. There’s a contradiction between style and subject here. In terms of style, the former often longs for an idealised past through the depiction of pre-industrial landscapes. In painting the decaying capitalist sublime, Steele destabilises the nostalgia for suburban normalcy—the ideal of the red-brick house, steady employment, and the good life has dissolved. Steele reminds us that the past we desire is never neutral—it is always framed by the fantasy of the nation or religion.

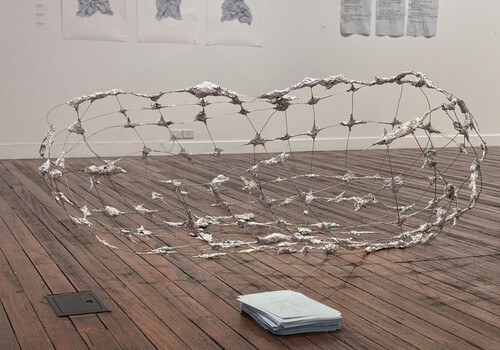

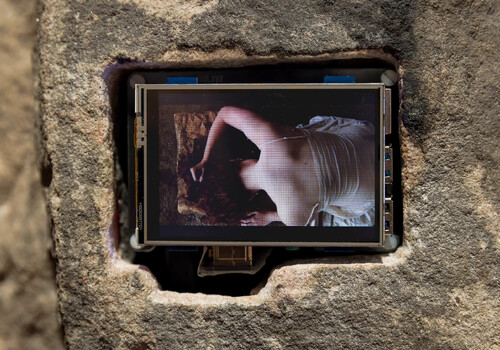

From Steele’s brooding, ecclesiastical paintings we move to Imogen Kerr’s Extraction (2025), a sculpture composed of rough, jagged blocks of sandstone. I immediately think about AGNSW’s Naala Badu building or The Cutaway at Barangaroo. These are the architectural coordinates for what SCA alumni and liturgical aesthete Felix Ashford calls “Sandstone Futurism,” a Sydney-specific architectural style “resisting homogenisation” (Pacific Hypermodernism) “by seeking necessity” (the city’s rich basins of Hawkesbury Sandstone). Kerr’s blocks are a far cry from the rendered, smooth tiles that form the momentous subterranean gateways to Central Station.

Imogen Kerr, Extraction, 2025, New Contemporaries, Sydney College of the Arts. Photo: Document Photography.

Perched within a carved recess is a small video player documenting an occult performance. We glimpse a bird’s-eye view of the artist leaning over, bunching her hair into the stone and grinding it in an exorcistic, self-flagellating ritual. Kerr reinstates friction into this raw material which is flattened and buffed for Sandstone Futurism (the contemporary aesthetic of settlement, perhaps). In her performance, extraction of the land is entangled with the extraction of the body; the morbid sacrifice that underskirts dispossession.

I can’t help but think about Steele and Kerr’s works when I reach Passages (2025) by S.U. on the upper level. The three-channel video installation presents what looks like CapCut-edited montages of Instagram-ready #SydneyLife reels. On the central screen, a sequence of clips: aquamarine waves, someone joyfully skipping into the pastel horizon, a busker at Circular Quay. The text “Life in Sydney Be Like” is overlayed in a cutesy font. Fade to black. A word appears on each of the three screens, “Memory. Moment. Becoming.” I’m waiting for the record to scratch; surely this is ironic. It never comes. S.U. is sincerely romanticising life.

S.U., Passages, 2025, New Contemporaries, Sydney College of the Arts. Photo: Document Photography.

Steele and Kerr conjure a sinister and eerie mood that feels at odds with the Destination NSW-coded version of Sydney presented by S.U. Can the eternally sunny, sexy, bimbo city ever be goth? It feels contradictory. Tha Bushranger speaks the city’s truth when he contrasts two images that capture these polarities: “Cranes in the sky cry screeching steel. Another soft pink sunset over the endless sprawl.” Development, in its many forms, has always haunted this beautiful place.

Levent Can Kaya is a writer and curator based on Dharug country. Through visual culture, he observes the longue durée of capitalism—its contradictions and cycles in ancient, contemporary and future worlds. He recently completed his Honours in Art Theory at UNSW.