Bachelor of Fine Art, National Art School

By Sky Zhou

The NAS grad show is on home turf, in the old Darlinghurst Gaol. Walking under the arch of skulls and crossbones, I am soon wedged among celebrating students, artists, and friends partying between former cells. In this place built for punishment and education, the show occupies a hinge between dark penal past and art-school future.

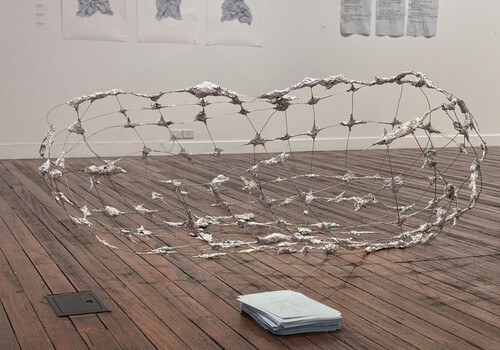

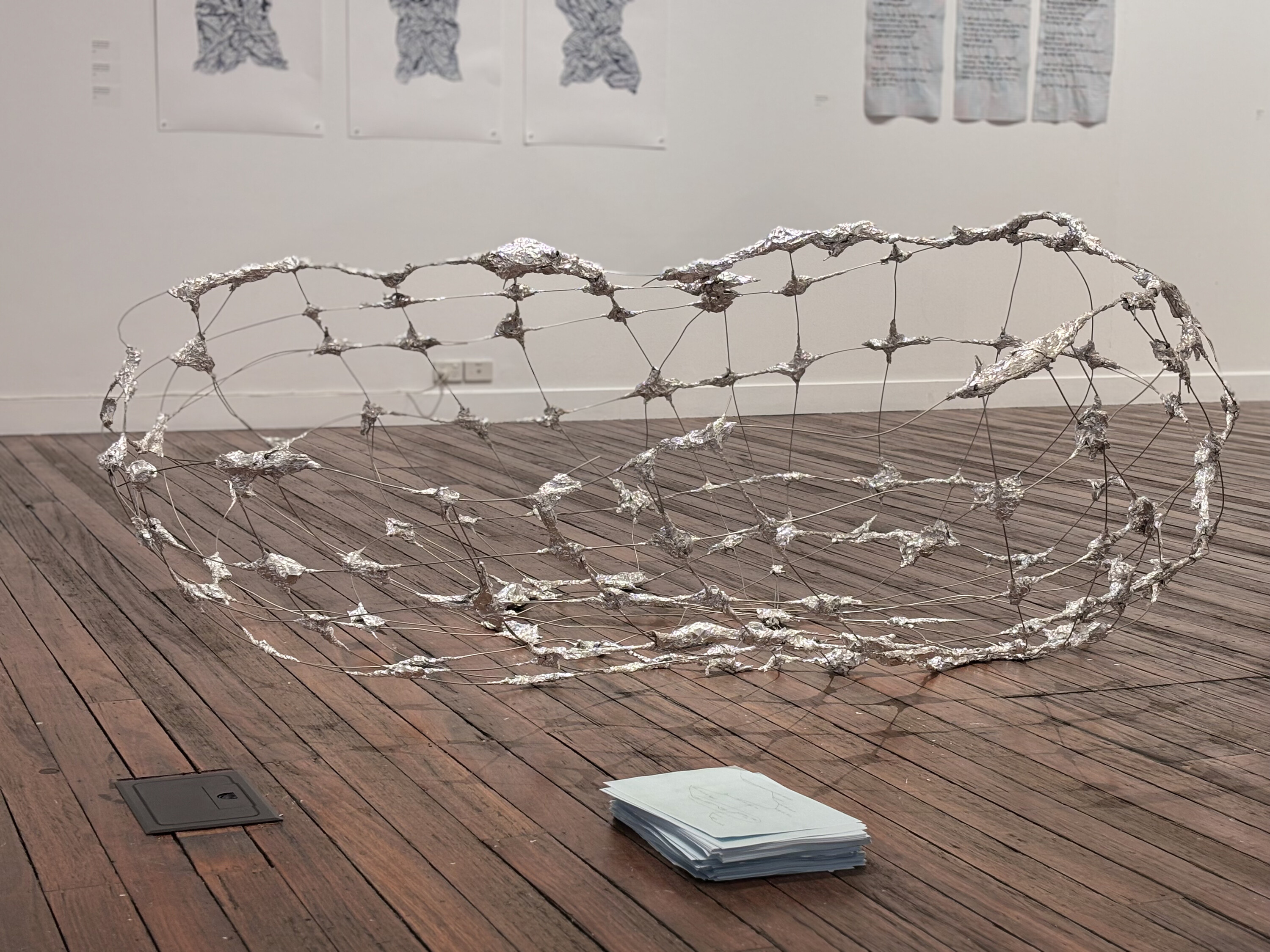

Installation view of Milla Watts, The Universe’s Soup, 2025, wire, tape and tin foil, 80 x 200 x 130 cm, and The What and the Where and the How and the Why, 2025, printer paper and ink, 30 x 21.5 x 6 cm, National Art School, Sydney. Photograph: Sky Zhou

Down in the cell block, I find Milla Watts’ The Universe’s soup (2025) squatting on the concrete. A taped tin-foil cosmos spills from a dense centre, wires twisting into a nervous system: kinked foil lumps form a world mid-collision. Beside the sculpture, a stack of A4s—Watts’ The What and the Where and the How and the Why (2025)—reads like a timeline of the world, from primordial ooze to prayer, war, and death. If The Universe’s soup is the “what”, these pages sketch the “where”, “how”, and “why” without quite closing the question.

Installation view of Tom Timbrell, And They Leave No Witness, 2025, etching on paper, 35 × 50 cm, and Dear Penny Wong, 2025, etching on paper, 25 × 35 cm, edition of 4, National Art School, Sydney. Photograph: Sky Zhou

I start to find my “how” in Tom Timbrell’s printmaking. And They Leave No Witness (2025) and Dear Penny Wong (2025) sit one above the other, two prints raging at the same political machinery. The upper print depicts two murdered members of the press. Below, a capitalised slogan flips Wong’s assurance that there is “nothing lethal in an F-35” as the jet faces us, flying out of the frame and turning reassurance into threat. Sketched lines echo grainy documentary stills and editorial cartoons, yet the images refuse to resolve into entertainment. Dear Penny Wong reveals how policy decisions made in carpeted rooms materialise elsewhere as rubble and bodies.

Installation view of Lola Jane Thompson, Artefacts of Collapse, 2025, screenprint on alupanel, dimensions variable, National Art School, Sydney. Image courtesy of the National Art School. Photograph: Peter Morgan

Lola Jane Thompson’s Artefacts of Collapse (2025) presents the clearest “why”: forty-four screenprints wrap a corner like a prophecy of late-stage capitalism. Pests, hazard symbols, buildings, chain-link fences, and clipped text are pressed flat on the metal, the language of warning signs and municipal design scrambled into a delirious urban vision. As I move in, I’m pinned between past chaos and a future of decay. Thompson shows not a single catastrophe but the everyday experience of living inside structures already rotting from within. Here, collapse is less a plot twist than the built-in contradiction of late-stage capitalism.

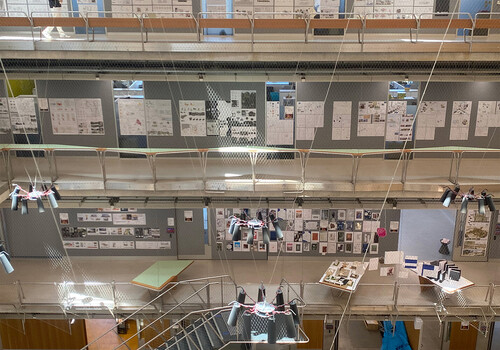

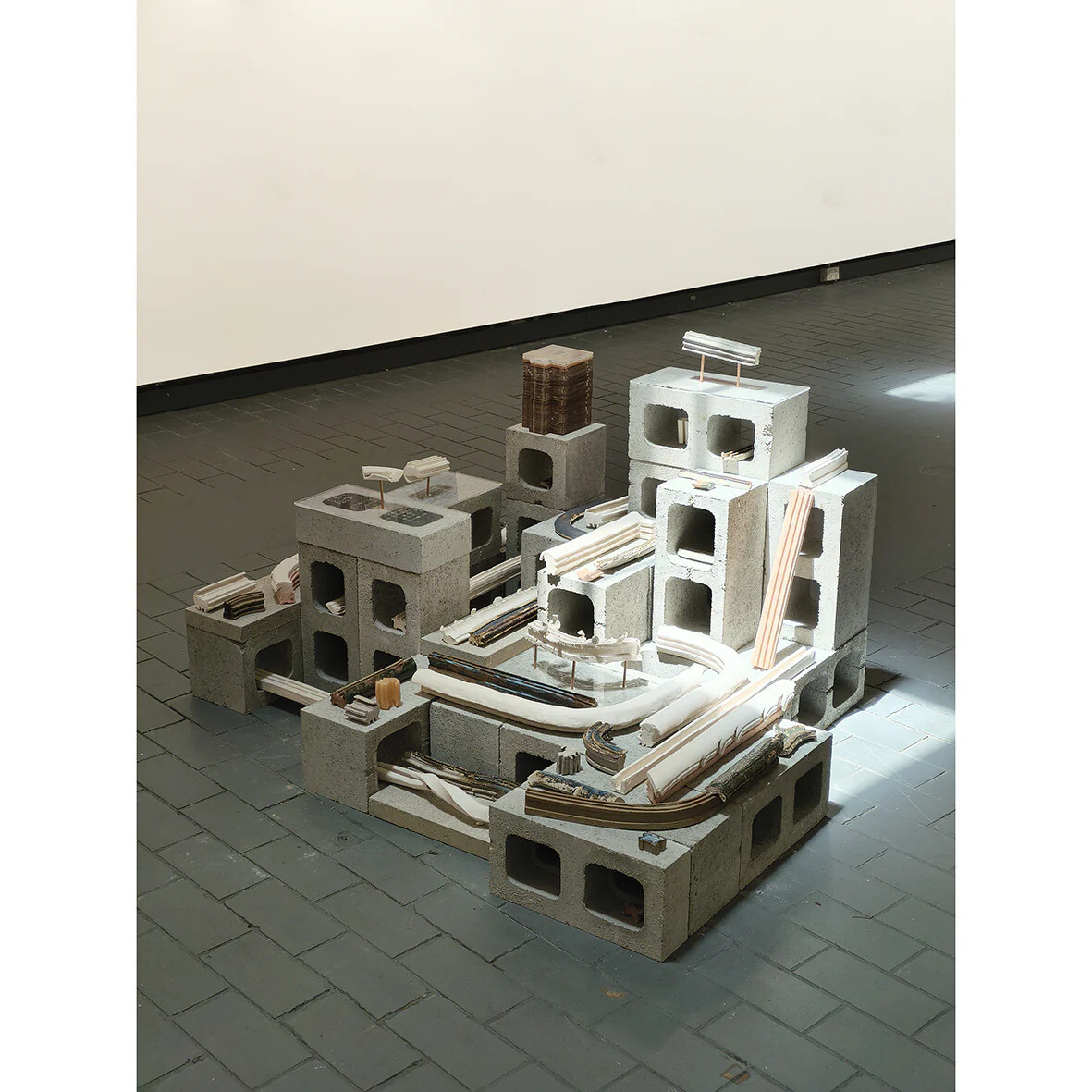

Installation view of Ziggy Stefano, Chaos is a Grievance with Something to Teach, 2025, stoneware, mixed glazes, besser blocks and clear acrylic, dimensions variable, National Art School, Sydney. Image courtesy of the National Art School. Photograph: Peter Morgan

I turn around and Thompson’s imagined cities morph into Ziggy Stefano’s Chaos is a Grievance with Something to Teach (2025). Besser blocks are stacked into a small metropolis, with clusters of towers and low-rise forms marking out a loose street grid. Stoneware pushes up through their hollow cores like rail tracks forcing their way through infrastructure. One stack is capped with acrylic boards, while another carries measurements and notes. The visual language of planning and optimisation is everywhere, yet the model shows an abandoned, post-event site—its precise statistics left behind by a culture already burnt out.

The “what”, “how”, “why”, and “where” play out in foil universes, protest prints, collapsing cityscapes, and ghosted architectures. The “who” is us: a generation that cares deeply about people, land, and the systems holding them together. Watts, Timbrell, Thompson, and Stefano don’t just mirror that concern, but sharpen it. If prison and art school both claim to “correct” behaviour, these works propose another education: art that breaks the status quo and refuses to let us pretend we’re innocent bystanders within the worlds we’re breaking and rebuilding.

Sky Zhou is an emerging arts worker living, working and learning on Gadigal land. Currently completing a Master of Curating and Cultural Leadership at UNSW, Sky is driven by a commitment to cultural exchange, dialogue and making space for diverse voices.