Bachelor of Visual Arts, Sydney College of the Arts

By Soomin Jeong

In the midst of the bustling energy of the SCA’s New Contemporaries opening reception, I found myself looking for a place to slow down. The artworks of Will Naufahu, Hanna Park, and Estelle Yoon drew me toward a kind of nothingness—what Taoist philosopher Laozi describes not as a total blank, but as an emptiness filled with the potential for presence.

Will Naufahu, Final Fantasy, 2025, stereo 64:13, installation. Photo: Document Photography

In a room I wandered into on the third floor, I found only stereo speakers and sheets of transparent paper printed with a list of films along with the artist’s speculative text on the moment when a ‘silent’ film screening shifts into a sonic experience. A low-pitched drone fills the space, eventually merging with the real-time noises of visitors. Will Naufahu’s Final Fantasy (2025) revives the experience of early twentieth-century silent cinema in this stripped-back gallery. This sonic work is edited together from seventeen silent films, rendering the sound of ‘silence’ : the whir of projectors, the hiss of recording systems, the incidental noises of audiences shuffling and whispering in the theatre. In the absence of cinematic images, we end up projecting ourselves onto the empty wall. The hum of this artwork folds into the hum of our own bodies. The noise is now alive. In de-visualising the visual, Naufahu turns the fixed life of film into something fluid and undefinable.

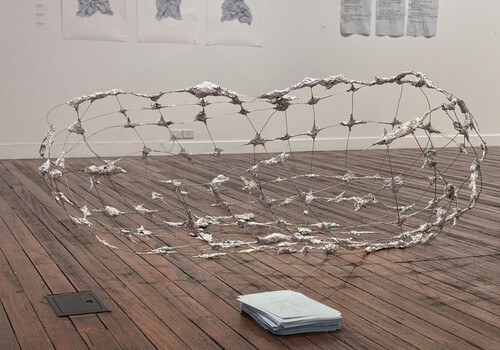

Hanna Park, Perimeter [verb], 2025, wire, paper clay, plaster, paint. Photo: Document Photography

After spending time in the visually ‘empty’ space of Naufahu’s work, I encountered Hanna Park’s Perimeter [verb] (2025). Park presents a white picket fence laid on the floor and curled up into a circle, made from paper clay and plaster. Instead of dividing the space, the fence stretches across the floor and into the air. I took note of the gap between each picket. The work explores the practice of personally and temporarily claiming public space. Even though this gallery does not belong to me, in this moment, I occupy it. I perceive it as mine, assigning my own emotions and memories to it. I imagine the white pickets as individuals in our society: scattered, grouped together, or forming strategic boundaries through cooperation. Am I occupying a place owned by no one? What does it mean to be present in a blank space, like the gaps between the pickets?

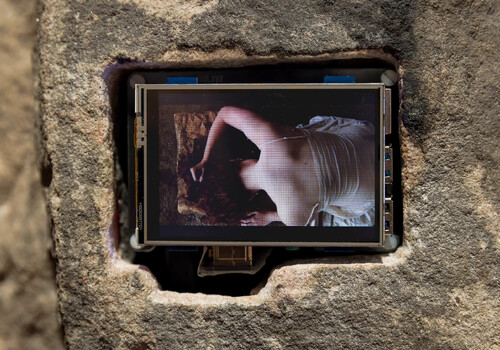

Estelle Yoon, 우체국 소포 (Post Office Parcels), 2025, glass. Photo: Document Photography

On the second floor, in a sunlit room, I encountered two glass replicas of Korean Post Office parcel boxes—one transparent, the other black and partially opaque. The boxes sit on cardboard-style plinths positioned at the same height as the gallery windows, absorbing the incoming light. Engraved Korean Post Office logos imply the transportation of invisible things from Korea to Australia. Their transformation into glass intensifies a sense of fragility and carefulness. As I contemplated Estelle Yoon’s 우체국 소포 (Post office Parcels) (2025)—seeing both their inside and outside at once—I imagined what they could hold. Yet, seeing my reflection and the movement of people through the space unsettled me. It echoed my own sense of vanishing and being emptied after migration, unsure whether I was absorbing the world or being absorbed by it—a feeling shared across diasporic identities. Still, the boxes show how that emptiness allows both containment and trace. In the shifting sunlight, the Korean letters are reflected on the white walls, extending the work’s quiet meditation on presence and displacement.

Coming back to Laozi’s sense of nothingness, the emptiness shaped by Naufahu, Park, and Yoon becomes a paradoxical invitation to appear. Each artist stages absence differently—Naufahu through sensory subtraction, Park through provisional boundaries, and Yoon through fragile containers of memory— and together they trace the shifting conditions of presence. Drawn into their works, I become an image of blurry noise, another picket in a boundary, and an untranslatable memory in transit. Their artistic strategies of becoming transparent—of removing what is ‘essential’—can be read as a willingness to be vulnerable and to invite audiences into a place of shared vulnerability.

Soomin Jeong is an emerging curator from Seoul, South Korea, currently based in Eora/Sydney. She is completing a Master in Curating and Cultural Leadership at UNSW.