Honours, Victorian College of the Arts

By Amélie Blanc

Amelie Thompson, Kitt Falkner Babbel and Alex Pug Williams invite an unexpected question: what do pigeons reveal about the way we see, and sometimes overlook, the world around us? Falkner Babbel’s dazzling pigeon puzzles, Thompson’s crooked bird-like legs, and Williams’ web of found objects foreground how human perception, creativity, and intervention shape our understanding of the natural and constructed world. Relying on what we have made for ourselves, we improvise like birds assembling nests from branches and candy wrappers scavenged from the gutter.

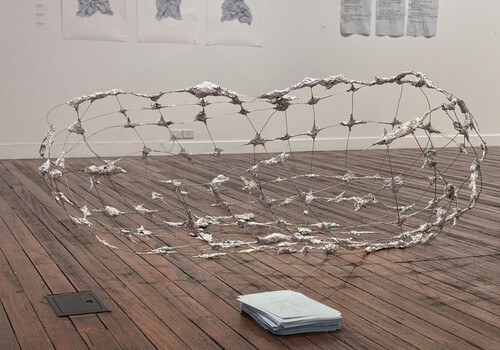

Installation view of Alex Pug Williams, Web of Detritus, 2025, Expanded polystyrene, rebar, 30 metre spring guide, wood concrete, concrete putty, asphalt, plastic, housepaint, bicycle spokes, bicycle handle bar, bicycle fork,[…], VCA, Melbourne. Image courtesy of the University of Melbourne. Photography by Astrid Mulder.

Pigeons’ nests, constructed from found objects and a few branches, can be unexpectedly resourceful, as the Twitter/X pageBad Pigeon Nests illustrates. In Web of Detritus (2025), Alex Pug Williams transforms this resourcefulness into a sound-sculptural assemblage, using human presence and action to explore materiality, space, and the traces we leave behind.

A mass of polystyrene forms its core, surrounded by found objects. Discarded items such as an ‘antenna fixture from mum’s roof,’ ‘Camilla’s viola bow,’ a ‘broccolini rubber band,’ are not just waste. They are remnants of relationships, memories and purposes. In the sculpture, they connect and support one another, forming a web that breathes, vibrates and resonates. What is the sound of waste, of polystyrene, of human-made landfill? During the performance, Williams activated the sculpture’s sonic qualities, striking and rubbing its surfaces, amplified by microphones embedded in the structure. During Williams’ performance, I attempted to put the delicate sounds onto the page. Revisiting my notes, I saw how inadequate they were in conveying the fragile, surprisingly melodic quality of sounds coaxed from landfill.

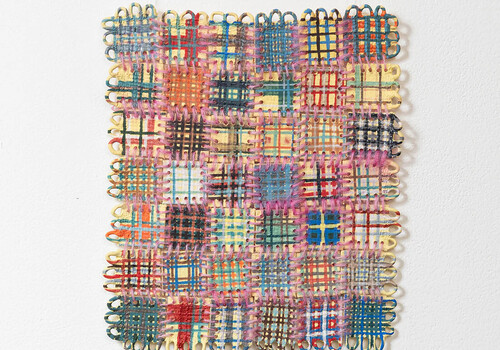

Installation view of Kitt Falkner Babbel, Iteration 1, 2025, Custom plastic canvas diamond art puzzles mounted with silicone on aluminium dibond, VCA, Melbourne. Image courtesy of the University of Melbourne. Photography by Astrid Mulder.

In Iteration 1 (2025), Kitt Falkner Babbel presents four plastic-canvas diamond-art puzzles depicting pigeons in their so-called “natural” environment. Here, the city replaces the rocky cliffs these birds once called home; as the Animal Diversity Web observes, “skyscrapers take the place of their natural cliff surroundings.” It’s a neat irony: the artificial has become the natural. Creatures often belittled are exalted here by dazzling plastic diamonds. The glittering, labour-intensive objects elevate an otherwise overlooked bird, turning everyday pigeons into something striking and almost uncanny. The images resemble surveillance photographs or paparazzi shots, humorous yet strangely significant, as if these pigeons might know something we do not. Yet this elevation is carefully staged. Real photographs of pigeons are transformed into a puzzle, a game, a completely human-made construct. The playful surface sharply contrasts with the reality of a species whose worth has faded through domestication and neglect. This tension highlights how uncritically we treat pigeons as urban background noise and how the artwork invites us to look again. Falkner Babbel prompts us to reconsider the value we assign to the species that live closest to us, whose existence is shaped, limited, and often compromised by human activity.

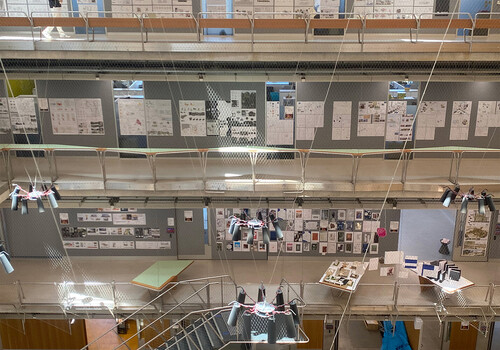

Installation view of Amelie Thompson, Class of 2025, 2025, Beeswax and metal wire, VCA, Melbourne. Image courtesy of the University of Melbourne. Photography by Lucy Foster.

Amelie Thompson’s Class of 2025 (2025) presents beeswax-and-wire sculptures that evoke the spindly legs of birds. Like Eva Hesse, Thompson’s use of beeswax communicates vulnerability and impermanence. The translucent yellow wax, seemingly hand-moulded over wire, creates delicate textures and layers, sometimes distorted, drooping, and bodily. These legs run in all directions, caught in a mass movement, calling to mind a waxen claymation cast. Reading the title, one might imagine the class of 2025 as a flock. Graduation suggests not only future possibilities and existential questions, but also the frantic, often chaotic work of completing assessments. Not to put words in these graduates’ mouths, but if their heads were metaphorically cut off during their final week, they might have kept running and working. Thompson’s wax legs zoomorphises this dynamic, presenting a caricature of a group driven by collective momentum, burnout, and disorientation.

A pigeon’s nest, built from discarded materials, becomes a vivid metaphor for humans navigating reality and facing the consequences of their own actions. In the pigeon’s case, however, it must adapt not to its own choices, but to the effects of human activity, highlighting both the resilience of these birds and the often-overlooked impact of our presence on the urban environment.

Alex Pug Williams, Kitt Falkner Babbel and Amelie Thompson suggest that we are not so different from these birds, and perhaps there is something to learn from how they make do with the detritus of human life.

Amélie Blanc is an arts worker and journalist based in Naarm/Melbourne.