Bachelor of Fine Art, Monash Art, Design and Architecture

By Eadie Rule

I did not expect Monash Grad Show to change the way I see the world. But faced with the works by Oscar Elms, Kirstin Charles and Amalia Série-Ruiz, I am presented with new interpretations of the everyday. Their works recall fragments of the familiar, but in ways that feel off-kilter. They offer a vitality to the inanimate, imbuing it with an unexpected life-force.

Oscar Elms’ Frankenstein-like assemblages are gritty, intricate and full of feeling. This series speaks to the legacy of Russian Constructivism and the ‘speech of materials’, whereby Elms’ Homer (2025) is the rebellious grandchild of Vladimir Tatlin’s Corner Counter-Relief (1914-1915). Eschewing the stark utilitarianism of its ancestors, Homer is bright and boyish. The work compiles Homer Simpson’s head with rebars and Chiko Roll wrappers, adopting the personality of an angsty cartoon-loving teen.

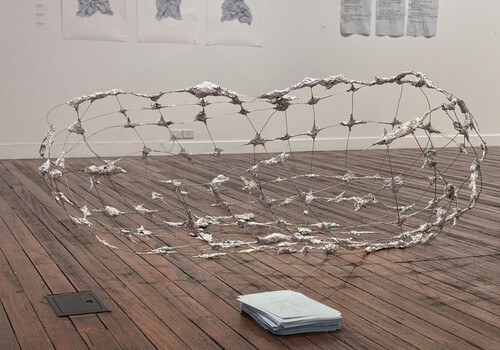

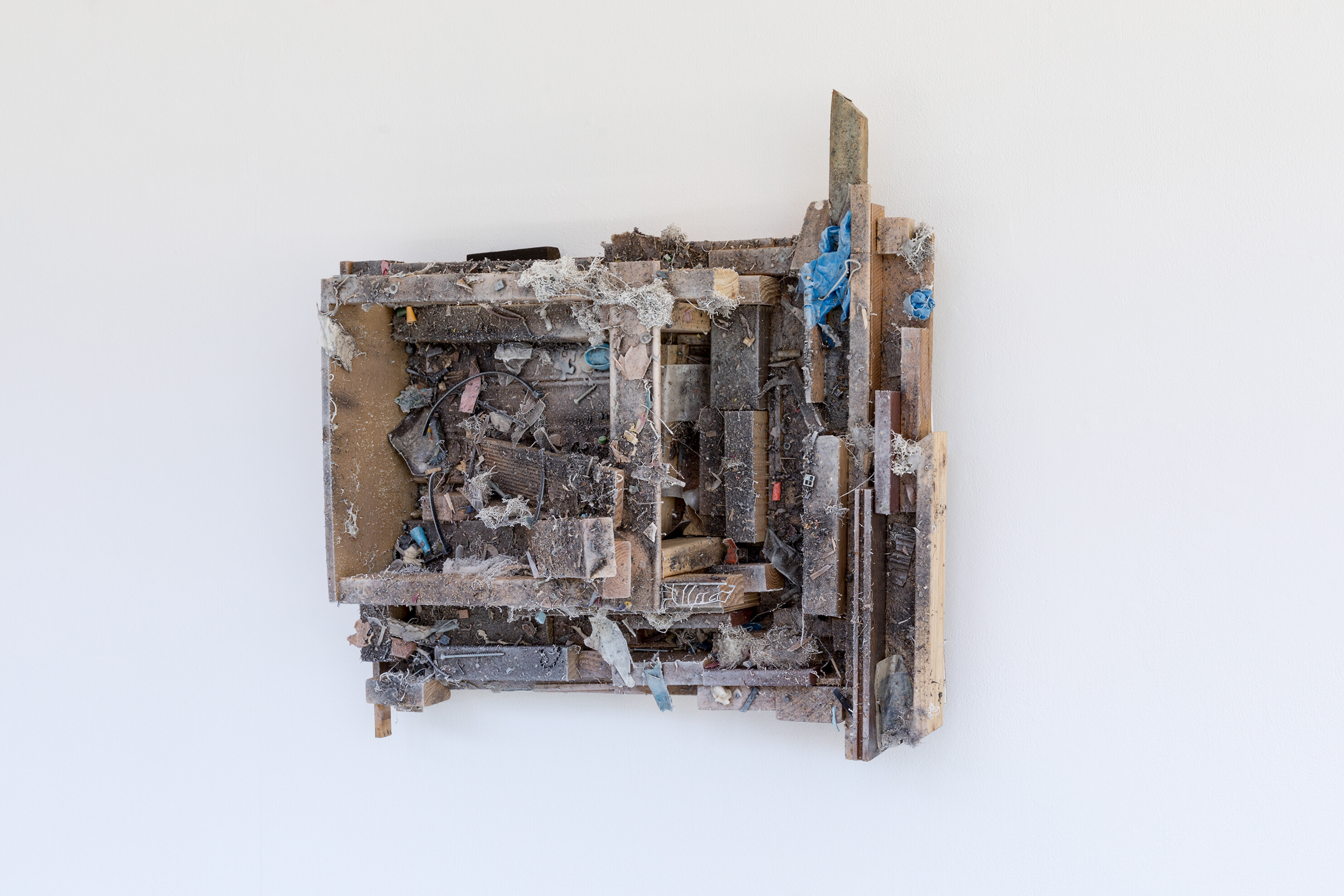

Oscar Elms, Make-up girls making-out 2, 2025, rubber, metal and studio refuse on wood, 85 x 85 x 40cm, Monash University Caulfield. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

Through his titles Elms cheekily points to the absurdity in the unremarkable. A personal favourite, Like being naked in front of a pet (2025), calls to mind a familiar moment of laughable vulnerability. In Make-up girls making-out 1/2/3 (2025) three wall-sculptures are adorned with dirt and dust, like icing sugar on a cake. Lace-like webs and doily fragments offer the wooden structures a charming delicacy. Gleaned from the outside world with their coating of grime intact, each work carries the trace of its original life.

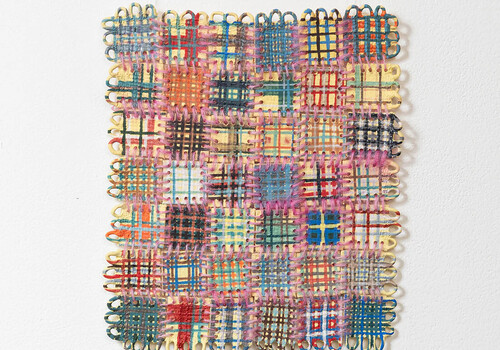

Kirstin Charles, Forest Floor, 2025, Stoneware, earthenware and terracotta clay. Stoneware, earthenware and underglaze glaze. Monash University Caulfield. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

Kirstin Charles’ lush Forest Floor (2025) possesses similar vitality, mounted on a plinth in the centre of one of the studios, transformed each year into gallery spaces. There is a wildness to Charles’ work as a biome of earthenware takes the shape of native flora. Plants including wild daisies and succulents explode haphazardly from a bed of leaf-litter, lichen and russet gumnuts. The disarray is as much an ode to life as it is to decay—a convincing ecosystem. Where unglazed forms ossify, bright buds of cerise and butter-yellow sprout. I feel compelled to pluck my own floral memento from the scene, certain a new bud will soon shoot-up to replace it.

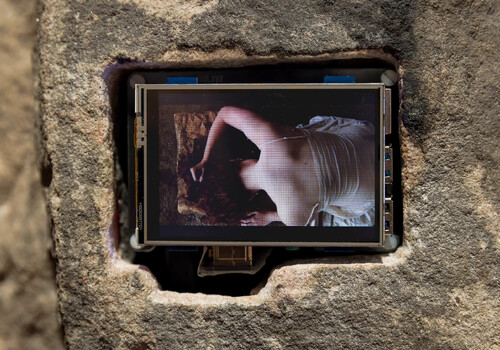

Amalia Série-Ruiz, Paillasson, 2025, unfired clay and video work, 100 x 200cm, Monash University Caulfield. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

Complementing Forest Floor, Amalia Série-Ruiz’s multimedia work renders a marine oasis. Despite the domesticity of its title, Paillasson (2025) which is French for ‘doormat’, the work would be most at home on the threshold of a coral reef. Overlaying the islet is a projection of geometric patterns that magnify the texture of each form. Their digital veil animates them further. White and blue shapes recall the movement of dappled light through sea water. Unfired, the colony of coral is vulnerable to destruction. Perhaps this is what Série-Ruiz suggests through her choice of title. Time will stamp its feet on this oceanic doormat. There is an urgency in this impending peril.

Elms, Charles and Série-Ruiz enliven the quotidian. Each borrow from the everyday in playful ways. For Elms, found objects assume the personality of a teen world. While for Charles and Série-Ruiz clay is returned to the vitality of its natural source. I feel a new-found affection for the mundane wonder of the ordinary.

Eadie Rule is an emerging writer in Naarm. She has just graduated from a Bachelor of Art History and French at The University of Melbourne.