Honours, Victorian College of the Arts

By Giles Fielke

Kissing has had a bad year. Physical affection and paranoia may be two sides of the same coin whose condition is constant suspicion. For months we’ve kept our close-ones close and everyone else in social purgatory.

In the painting section of this year’s VCA Graduate Exhibition, Evelyn Pohl’s series of small, monotone stills from the TV series Gilmore Girls depict moments in the show when the characters Lorelai and Luke kiss. This sequence of small, horizontally installed canvas studies unconsciously operated as the fulcrum for my memory of the “Grad Show” this year.

We were lucky to attend. In two swiftly manoeuvred groups of writers, we were charitably accompanied by VCA-supplied “minders” to ensure we abided by the COVID-Safe regulations on campus. In Pohl’s work, as with many others in the exhibition, there is no longer any distinction to be made between the screen, between the documentation of activity and art. Yet there remains a hard distinction about who is allowed inside the art school and who is not. Art as ideal is not art as experience, now it appears to be the opposite: its impossibility.

Gilmore Girls is conflated, in my mind at least, with another US teen drama called Gossip Girl. The six-seasons of Gossip Girl clearly made a massive impression on an affinity group of which I now count myself a part. Gossip as a category of (gendered) discourse operating in and around sites of social interaction often carries a pejorative meaning. Perhaps the attempt at representing this everyday talk by Robin Dunbar, whose odd speculation on the origins of language as evolutionary psychology, was published at the end of the twentieth century, can help. Dunbar relates gossip to “low-cost” vocal grooming, something akin to how primates manually groom one another. To gossip is to preen, but to groom another is now considered inappropriate—at art-school, unkempt is à la mode. Gossip is horny. I detect, or perhaps project, the anxiety of physical intimacy across the entire field of work on display—we must elevate gossip to the status of art.

Gilmore Girls aired from 2000–2007, Gossip Girl from 2007–2012. The nostalgia for a show which began in—I am assuming—Pohl’s early childhood, is interesting for the way it instantiates the latest cycles of “generation nostalgia” (see Jasmine Penman’s excellent take here), which seems to have been recurring at ever-smaller intervals, approaching but never quite meeting the present in the way that a parabolic function advances towards, but cannot touch, its Cartesian axis.

Many artist’s work installed at the VCA graduate exhibition have gone uncommented upon in the Mass Memo project. Yet speaking meaningfully about the entirety of the work on display easily becomes misguided and relativist. Only the works that struck a chord in the limited time we, happy few, spent in the gallery or viewing online may be spoken of.

An example, Brayden van Meurs—whose dehydrated ants and a pain au chocolat from Lune Croissanterie where among the more interesting “details” listed in the works—used parachord to cross the void in the Stables and above the Honours studios. Thandiwe Bethune’s second-floor performance amongst chairs and featureless office paraphernalia was arachnid and affective—even intimacy with and amongst others is foreclosed. All we have is ourselves (fortunately we’ve been divided).

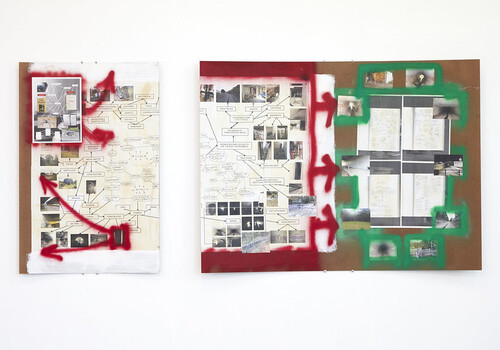

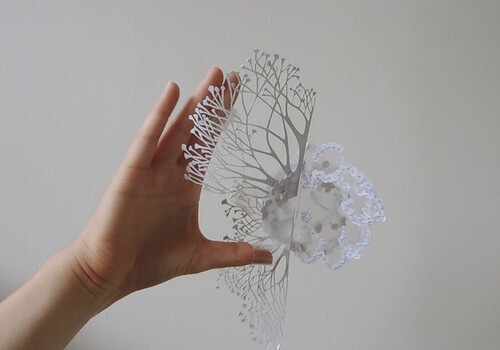

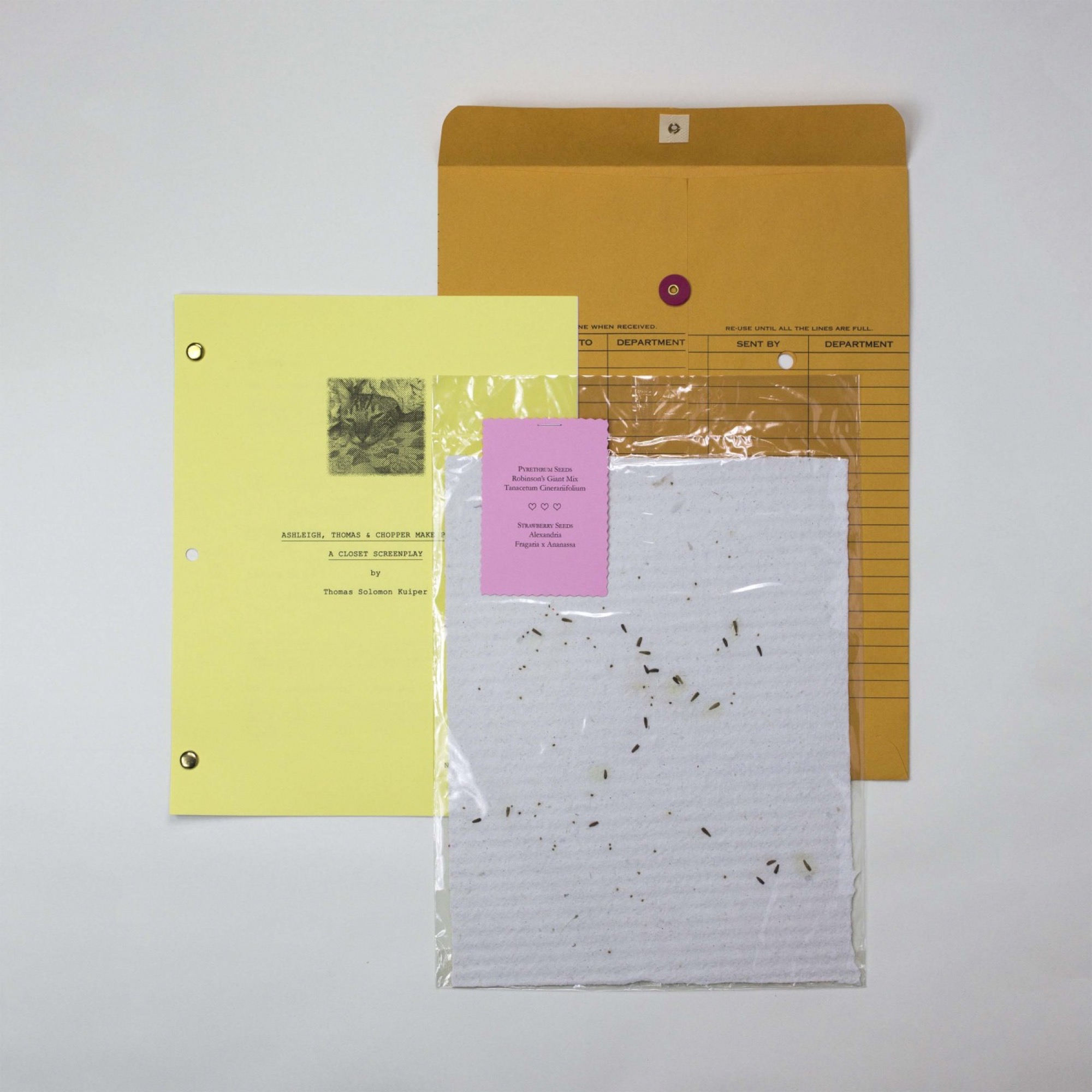

Hugo Blomley’s helicopter struggles to take flight against the brutalist “Zig-Zag”—a reproduction of a Gerrit Rietveld chair from the 1930s, inspired by De Stijl—on a parqueted stage that situates us as truly child-like and removed from the installation. Thomas Solomon Kuiper’s documents at the Stables’ northern-most wall, an archive of seeds or “others” desperately tries to exile anything alien from the self yet can only call on the lives of their confrères to complete their many screenplays, in the closet with their cat. To do “whatever your heart desires” is the final call. I think of the seeds as gossip, groomed or to be fed to the garden, of cats consenting to be molested by wondering human hands.

Kissing is banned (by the mask); even as the masks disappear the world emerges, hornier. If modern art rents a functional separation of artist from their artwork—or at least has attempted to (Ernst Gombrich once remarked: “there is no such thing as Art, there are only artists”)—the collapse of representation sees the suture as a solution and is our peculiar symptom: the work is a performance of the artist’s very being. So what is it that we, the participant observers, desire? The work or the worker? You scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours.

Giles Fielke is a writer and editor of Memo Review.