Bachelor of Fine Art (Visual Arts), MADA

By Grace Watson

More intimate than sight, closer than sound, more enduring than taste, and more certain than smell, touch is a sense inseparable from our experience of the world. Yet, in a year when touch is taboo, the artworks in Monash’s 2020 graduate exhibition reach out to their audience in a way that redefines touch despite the boundaries of distance.

To touch is to mould.

Harmonizing the aesthetics of organic and geometric forms, artist Liz Pederson has created a collection of hand moulded and 3D printed ceramic vessels, all unique, though united by their complementary pastel tones and endearing peculiarity. Contested Hands (2020) dissipates any opposition between digital processes and physical media—the former having enabled us to form connections amid physical constraints. Pederson contemplates without condemnation the similarities and differences of being moulded and formed by the digital hand.

To touch is to know.

Sofie Larkin’s Painted Personalities (2020) riffs off semiotic colour connotations and her own experience of synaesthesia to introduce viewers to important people in her life. Larkin extends an invitation through each colourful, abstract portrait, bypassing surface appearances and instead offering an opportunity to be touched by another’s intangible soul. Viewing each portrait felt like a conversation as I spent time with each subject and imagined how we might interact.

To touch is to embrace.

To be hugged is a profound experience of touch, offering intimacy, comfort and a holistic embrace, both in the physical and beyond it. Yet, hugs are characteristically shared with another: what can be done when this touch is taken away? Through her series of instructional line drawings, Sidney Robertson’s Self Hug (2020) provides an interactive guide, acknowledging the shared nature of our isolation and allowing the viewer to discover the power of their own embrace.

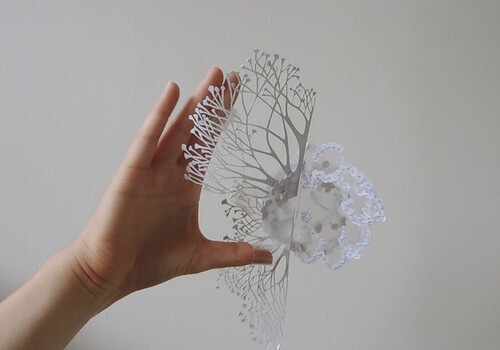

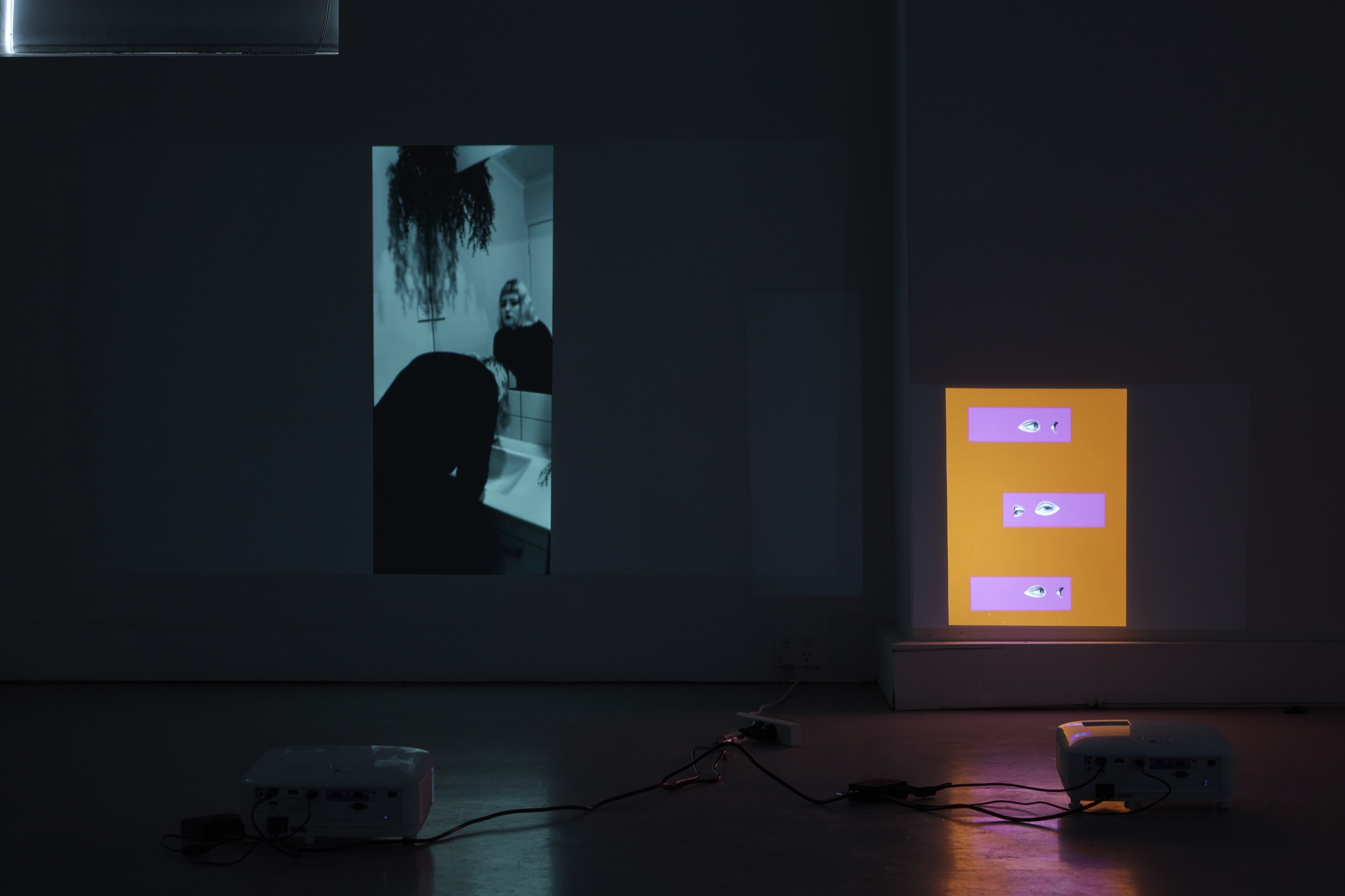

To touch is to hold.

Unlike the warm embrace depicted in Robertson’s fine line illustrations, Shannon Connelly’s intimate, eerie Parallel Worlds video series (2020) explores the mental and physical grip that isolation and stillness hold us in. Projected low to the floor, Connelly’s work forces viewers to sit still and be held in their place, fully immersed in the slow-moving scenes. The video pieces centre visually and conceptually around Connelly’s own troubled self-reflection, yet she emphasises that these works are created to be “experienced and relatable to anyone”. She holds us in our place, but Connelly reminds us that we are not alone there.

To touch is to create.

Reminiscent of Lygia Clark’s haptic Bichos of the 1960s, Imogen Slater’s 29 Plastic Forms (2020) reminds us that to touch is to create. Each of the delicate recycled sculptures “address discarded objects with a sense of possibility”. The forms scattered on the low-lying plinth are inanimate, yet Slater’s complimentary video piece depicts her hand turning, squashing and folding these objects. The creative possibilities are endless, but tactile interaction is essential. Without it, these objects remain stationary and isolated. Maybe we are more like them than we realize.

Amid a time defined by the avoidance of touch, these works collectively find new ways to reach out to viewers and bring what is distant close. Rethinking touch has catalysed these graduate artists to connect with audiences in new and profound ways, inviting forms of contact that expand beyond the merely physical.

Grace Watson is curator, programmer and arts educator working on the Wurundjeri and Bunurong lands of the Kulin nations. She has a strong interest in relational aesthetics, with her work and research focusing on drawing connections between historical and contemporary theories and practices. Grace is currently pursuing her honours project in Art Curation at Monash University.