Bachelor of Fine Art, MADA

By Victoria Loizides

Is there a word for when a painting feels like a sound? Unfortunately, Google doesn’t have an answer. But it was all I could think about after stepping into room D215 and hearing the distant chimes of a video work from downstairs, (I found out later that this was the work by graduate Daniel Kuang) as I stared at a print of an alien-like hand. A hand that was definitely going to pluck me out of oblivion. I’ll be the girl who died via an artwork. How very Velvet Buzzsaw of me.

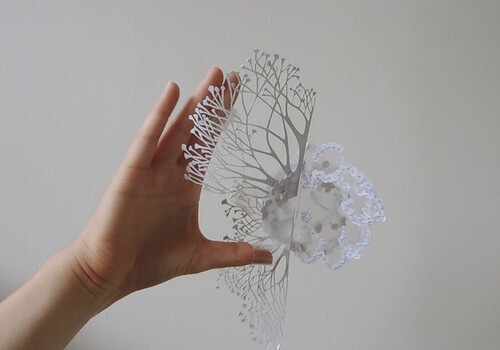

Well, I didn’t get plucked. The hand belonged to Celeste Lloyd and is part of a series of cyanotype prints that recognisably experiments with mystifying mundane objects through a variety of cerulean tones. Suddenly, the hand in question stops being just a hand. It becomes threatening, unknown and alien to us.

In its extra-terrestrial (or even ghostly?) fashion, the hand is revered within a ring of light and mounted inside a mirror lookalike. These basic forms inverted by light- sensitive paper resemble minimalistic principles—limited colours accompanied by geometric shapes, while the colour scheme echoes an eerie x-ray with the intention to uncover something unknown.

This rings true particularly for Photogram in Blue 2 (2020), in which a vase-looking shape is mirrored down the middle of the print. Towards the bottom, the colours combust in on themselves, resembling a television with no signal, playing static.

Can you hear it?

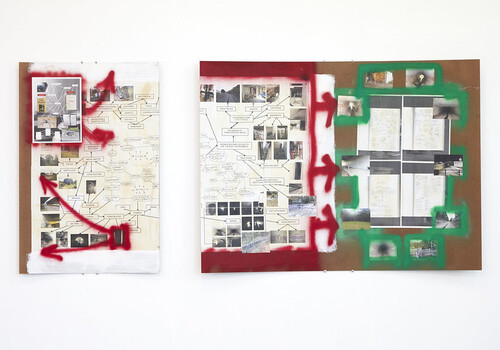

The melody suddenly changes as I walk to the adjacent part of the room. An emphatic mix of bass, drums and distorted guitar bounce off Connor Bugelli’s prints, evoking a sense of threat. The scratchiness of a print on linen forms the abrasive colour scheme used to envelope us into a gloomy cloud. However, this gloominess has a brash veneer. Instead, the works present themselves as a relinquishment of moral responsibility, particularly in Immorality is Neat (2020), where even the title commits to depravity.

It is through these themes of depravity that honesty is uncovered. Bugelli’s heavy sculptures and large-scaled prints bring you sincerity without a touch of irony, making it the pictorial equivalent of heavy metal; they are to be taken at face value. Take Immorality is Neat (2020), where a series of random bleeds of ink cover most of the canvas, married with the left side, where the ink takes the shape of an intentional design. These opposing sentiments—controlled and uncontrolled—are just like a sheet of a musical score: scribbled symbols on a page coming together to create something devastatingly honest.

It is no wonder I’m taken with this earnest attitude as I encounter Lhotse Collins’ work, which follows the narrative of colonialism: a history that bleeds into our future. Ghosts who tend to their own (2020) is composed of collected rocks, found shells, manipulated sheep wool and twine—materials associated with land transformation. Yet another gentle nod to the act of appropriating land in the name of colonial dispossession. At first glance, Collins’ work appears to hold an ancient sensibility (the domestic craft lends a hand to this feel). In the middle of the room, a Viking loom made from a found timber rack with hand-spun linen is weighed down by railway stones, resembling a pendulum stuck in time.

The work reminds me of site-specific practices but under a minimalistic pretence. Here, this sentiment is a double-edged sword. The works engage with the site to open up a visible space of decolonisation; they emphasise the pre-existing form of the building, as if the sheep wool embedded into the wall and stuffed into the cracks of the floor were there all along.

I am always reaching out for a sound: a cry, a laugh, a door opening. The sounds that can communicate without words, just like artworks. They open up different portals of communication. And these artists demonstrate that the spoken word is penultimate to the music of art-making (even if this was unintentional). I guess I have you to thank, Daniel Kuang.

Victoria Loizides is an emerging writer currently studying art history and curating at Monash University. She co-runs VITRIIN 5000hp with Margarita Kontev, a blog dedicated to art criticism unbound to academic and institutional ideals.