Honours, Victorian College of the Arts

By Sebastian Kainey

In normal circumstances, the VCA Grad Show opening has felt like a party. With large crowds of people, alcohol and loud music, navigating the congested galleries was at times fatiguing. I would constantly have to fight for space to view the art. This year, in a strictly timed viewing session reserved for industry, I was met with the opposite. No crowds, sober and quiet. My University of Melbourne colleagues and Memo editors were guided through the studios-turned-galleries at the VCA Southbank campus at record speed. A great sense of urgency became apparent; I was no longer fighting against opening night attendees; rather, I was fighting against time. In the honours student galleries, the exciting works that caught my eye all involved a considered analogue process to art making. Common amongst these works were the concepts of temporality and memory.

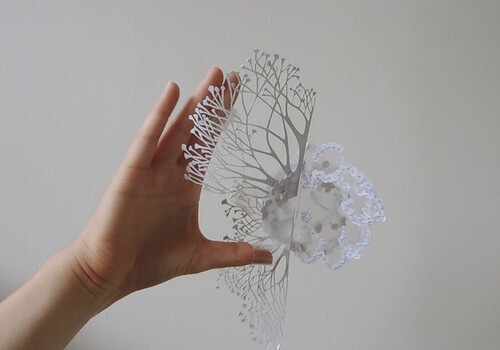

Nina Rose Prendergast’s photographic installation work, Black Metal Drapery (2020), appeared as a frieze and mimicked the natural degradation of large-scale marble statues. Marble degrades when exposed to natural elements; layers of rock are slowly removed, revealing underlying surfaces. Prendergast referred to this process in her series, in which cropped images of ancient marble statues were housed in an acrylic casing, which acted as a kind of vitrine. Prendergast defaced the vitrine with laser cut designs, creating similarities in line and shape with the marble figures. She imitated the deterioration of these sculptures, inserting a layer of human intervention in the work.

Skye Malu Baker’s lithographic prints also explored an analogue mode of copying. The prints, which were created from a stone printing block, were displayed in various locations in the space. The Past Continuous (2020) read like a map constructed of an amalgamation of architectural fragments. The work mimicked the way memory works in relationship to places once visited, and suggested a model to recall one’s journey. As such, relationships were established between works. Hidden around the corner, hung low to the ground, was a ghost print, created by skipping the re-inking process. As the image fades, does our memory of these places also?

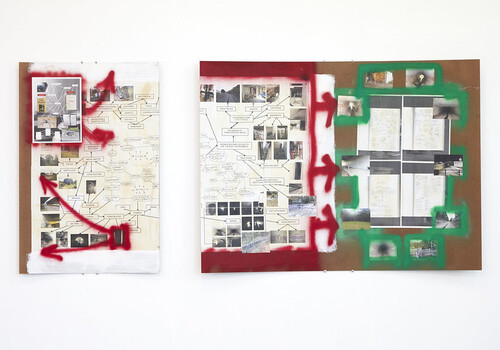

Lachlan McKee began this year working in the discipline of painting. Informed by this way of thinking, McKee tangled the formal qualities of two-dimensional works on paper through collage. The cut-and-paste imagery of colour patches, line drawings and paint accents sourced from McKee’s painterly practice and studio were hard to identify in this final collage form.

A new visual language was developed within the bounds of the paper support. The relationship between the images pasted onto the paper shifted and new connections between the elements of each collage presented themselves. Pictorial forms and figurative symbols blended together, revealing something else in-between.

Finally, the ghostly photographs by Edward Dean seemingly depicted foreign scenes of the natural and built environment. Complementing these images were a series of forms, Sculpture 1–3 (2020), which protruded from the gallery walls as if they were part of the built environment. Mounted in cut-out sections of plasterboard and displayed in close proximity to the ground, the alien forms were constructed using a number of synthetic and organic materials, including dried meat.

The autonomous nature of such material meant the work would continue to grow and morph in unexpected ways as time passed. Bringing a form of controlled chaos to the work, Dean’s sculptures added an element of organic intervention to the built environment.

Time and its inherent connection to memory were central themes in the work of Prendergast, Baker, McKee and Dean. In the context of the year that 2020 has been, it is clear why these Honours students are working in this way. These artists have exceptionally demonstrated what is possible in periods of precarity.

Sebastian Kainey is an emerging writer and arts worker based in Narrm (Melbourne).