Painting, Victorian College of the Arts

By Jenna Grace

The Fibonacci sequence is a continuous fraction—a medieval discovery that describes how nature follows predictable ratios in spiral patterns. This old-as-time algorithm dictates shapes in our natural world—flowers, shells, hurricanes. It also mapped a plague of early thirteenth-century rabbits in the north of what is now Italy. The sequence was observed by Fibonacci in this bunny breeding pandemic, and today is used by some contemporary researchers in predicting the spread of the COVID pandemic. The awareness of patterns continuously spiralling across time was a central theme in the 2020 VCA graduate painting exhibition. Although neither rabbits nor pandemics were referenced explicitly, the works that I dwelled upon all seemed to embody concepts of time and measurement.

My first pause focused on a pause. LuLu Smith’s oil paintings seemed like a long, conscious breath. Visually, this series is somewhere within the remit of Prudence Flint, Jeffrey Smart, or an on-pause pastel from a Wong Kar Wai film. Aiming for mindfulness, looking into these small-scale, gridded filmic moments recorded in oil on linen, I felt drawn into the artist’s solitary space—whether it be reality or dream. It was like a friend had invited me to take part in a moon meditation, and I really love the moon. I walked a little slower after this series.

Going from presence to a glitching screen in a Farmville-style mobile game felt appropriate for the year that has been. It was not, as I first thought, a kind of digital 2D frozen image reflecting the great pause/pivot of 2020—it was insatiably better. Sophie Day is an artist and a cricketer and her digital print series, It’s A Good Day For Cricket (2020) feels playful and hopeful. The made-in-Microsoft-paint / post-internet art style was what tricked me at first (a doosra?), and I wonder if this was what Day wanted—the digitisation of group activities seen in abstraction. Perhaps. Cricket in the expanded field. Probably. I do know, in spite of intention, it was fun. It had numbers. I guess they were counting runs, although I didn’t understand them even after googling “cricket”. And I think that is ok. Actually, I think the mystery is deliciously refreshing. And the abstraction of time recorded in bright, bold colours also recalled for me the current show of the late John Nixon’s Experimental Painting Workshop at Anna Schwartz Gallery.

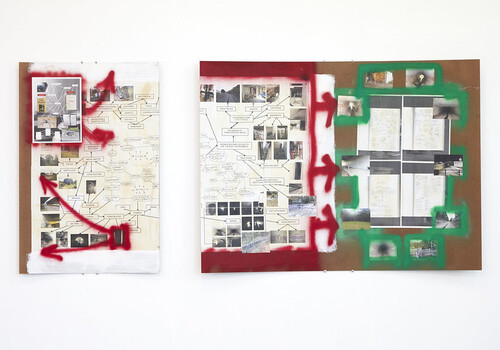

Blake Widdicombe’s environmental graffiti panels capture the negative space of shadows. Leaves and foliage were stenciled with primary colours, plus black and green. The meeting of Widdicombe’s background as a street artist with the shut-downs of the pandemic year has seemed to result in a forceful combining of the urban with the natural. The historically metropolitan street art practice now physically echoing the bush. Although, capturing a moment, there is a sense of frenzied movement. This impressive, impressionist en plein air graffiti instills a sense of trust in organic time and order in contrast to the rigidity of the city.

Jieun Ha’s oil on canvas series at first gave me nostalgia for the decorative wrought iron window grilles and gates of my childhood. The series title, Golden Ratio Love (2020), reflected the artist’s abstracted focus on the golden spiral, also known as the Fibonacci sequence. Was this ratio warped by love, or commenting that love followed predictable patterns? Or was it an abstraction of a model face, Gigi Hadid’s facial symmetry, as a golden ratio? Either way, it is a marvelously modernist and mathematically measured meditation on universal love.

The Fibonacci sequence relates to applying mathematics to predict the patterns produced by nature and the infinite. While the 2020 VCA graduate painting exhibition did not necessarily follow this sequence—as it was, in all senses, unpredictable—the graduates present the unique experience of quantifying their own time in isolation. No other cohort has been so remote from their studios, peers and teachers. But to see in art a continuous fraction makes for a truly affirming, reflective and stunning encounter. I was happy to unspool and unmeasure time here.

Jenna Grace is an arts educator, and a Research Assistant intern at the Shepparton Art Museum. She is completing her Master of Art Curatorship at University of Melbourne, within the School of Culture and Communication. She is a practising artist with a background in film production and community arts engagement.