Drawing and Printmaking, Victorian College of the Arts

By Rachel Pakula

Emma Kleeberg’s IT’S ABOUT YOU, bed as therapy (quilt), and bed as therapy (pillow) consists of a satin sheet hung from the ceiling, hovering in the centre of the room adjacent to a mattress set on the floor, adorned with one pillow and quilt. One print fills the sheet. It is an unblended colour gradient that looks like it was made with a highlighter tool and digitally handwritten text—slightly untidy, clumsy—“I HOPE YOU SEE THIS AND KNOW IT’S ABOUT YOU”. Below this text, in a lighter opacity, is written, “BC IT’S ABOUT YOU”.

Standing before Kleeberg’s work, I am instantly transported. It’s a blessing to be in the bed of another. To be wrapped up, enveloped by their scent—inherent, insidious, ephemeral, seeping through crevices and into my dreams. I found your hair all over my sheets, and your smell. I didn’t want to wash them because it would carry you further away. Each marker of your presence, I deliberately remove them, I strip my bed and peel off us.

Kleeberg’s installation provides us with a moment, frozen, resisting the intangibility that comes with the exhibition—the start and end date remain ambiguous, and this year a lack of visitors altogether. I missed a whole room in the drawing and printmaking department because I wanted to spend all my time with Kleeberg’s bed. The digitally printed paintings show more clearly on my phone than any photos I’ve ever taken at an exhibition. The digital, often associated with distance and disconnectedness, maintains a directness—the viewer can imagine Kleeberg drawing onto a screen with her finger, making quick, intuitive and expressive lines, stopping spiralling thoughts by releasing them through the interface. The messages are short, sharp and unmediated. They are not compromised to be made understandable or palatable; they are simply there, waiting to be understood. I had a dream about this work where the artist spoke, and the words appeared as if created by a speech-to-text function. The abstract becomes definite. We are tired of explaining—you can come to us.

I know my person is somewhere else, at the other end of an abstract thread between us, that they may not notice my tugging. Kleeberg’s work reveals a new end to my thread—one which doesn’t require a reliance on you to remember us. I want you to be free. So instead I have held onto these two ends—me, thinking about us, knowing and remembering us, feeling us with resolute certainty, absolute, unwavering, doubtless clarity.

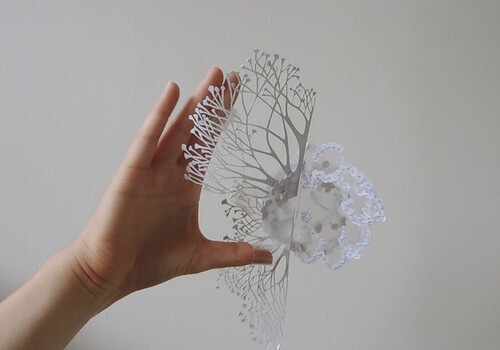

Mi-Mi Fitzsimmons’ To Jun, TSITM, Mamihlapinatapai and FSSS sat in the background of many of my photographs of Kleeberg’s bed, waiting for me to notice how much I wanted to know them. I wanted to know them as much as Kleeberg’s loud colours, Nisha Hunter’s yellow turmeric or Nelle Rodis’ bold knitted charcoal prints next door. With raw silk, stainless steel silk and monofilament, the threads of Fitzsimmons’ works are so fine you might not notice them but for the weaving bringing them loosely together, and the frames holding them in place. One is unframed and hangs from the ceiling. They are in a realm between this one and another, magically transparent. Part of their existence consists of how much I want to see them better, the longing for knowledge and closeness, for definition which brings me closer to you. Sometimes you have to work for the privilege of knowing someone. “Mamihlapinatapai” is how I felt before we said “I love you”. The title is a borrowed Yaghan language word spoken in the Tierra del Fuego, which can be translated— rather uneconomically—as “looking at each other hoping that either will offer to do something which both parties desire but are unwilling to do”. It is like a game where we must intuit the rules and choose to admit something we cannot take back.

Christina May Carey’s Touch the Skylight shows a HD video on a 43-inch flatscreen, parallel to the floor, knee-height, in the centre of the room—I look down at the screen, staring up at the bright blue sky dotted with soft, fresh clouds, rain falls towards my face, held at a distance by a skylight window. We are so close, yet so many layers live between us, flipping us over and over in limbo. Lifting my head, a projection of the moon shifts through its phases on the wall. In the corner up and to the left is an iPad, mounted to show a rippling underwater view of a swimming pool. It prompts me to remember those timeless dreams I’ve had about swimming in bathrooms, through little nooks and tunnels like a flooded ancient bath-house.

It’s all bitter-sweet. We are grieving, but glad, tentatively happy. Everything that happened this year is sun and rain, hinging on the knowledge that all the good things that happened only came because we were living this way. All the beauty of expression flames with personal struggle and sorrow. In the gallery, we are being pushed to move on, quickly, forward to normal life, being told we’re out of time at this section, it’s time to go to the next studios. Shepherded forward the ushers are performing the forcefulness of the year, but we’re not ready to move on. Even after months in one room, I could stay in these rooms for months more. I could sit with the beds, the weaving, the video, the way I watched the same shows on repeat at home. I would do it all again.

Rachel Pakula is a Melbourne/Naarm-based writer of Jewish heritage, undertaking her Honours in Art History at the University of Melbourne. She is writing her thesis on walking theory and the sublime.