Bachelor of Fine Art (Honours), UNSW Art & Design

By Ava Lacoon

Honours students at the 2024 Annual are as expressive and loud as ever, even as UNSW’s Paddington campus is enveloped by grey concrete. UNSW was once more akin to a sandbox than an Optus store. Murals painted by artists including Jason Phu have been eradicated by neutralising grey paint and turpentine, like the school’s previous namesake: College of Fine Arts. As Grad Shows become increasingly corporate fare, criticality would seem to be pacified. However, the artists at this year’s Annual deploy humour, joy, and trolling to critically navigate institutional resistance.

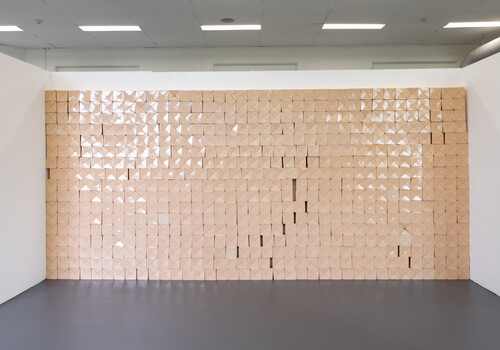

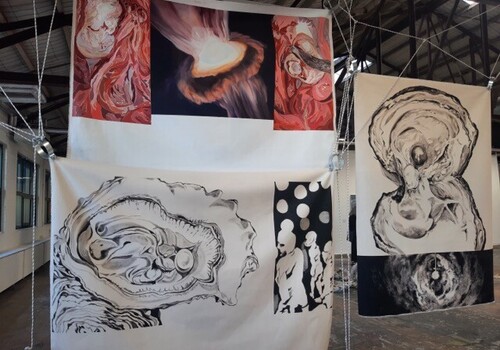

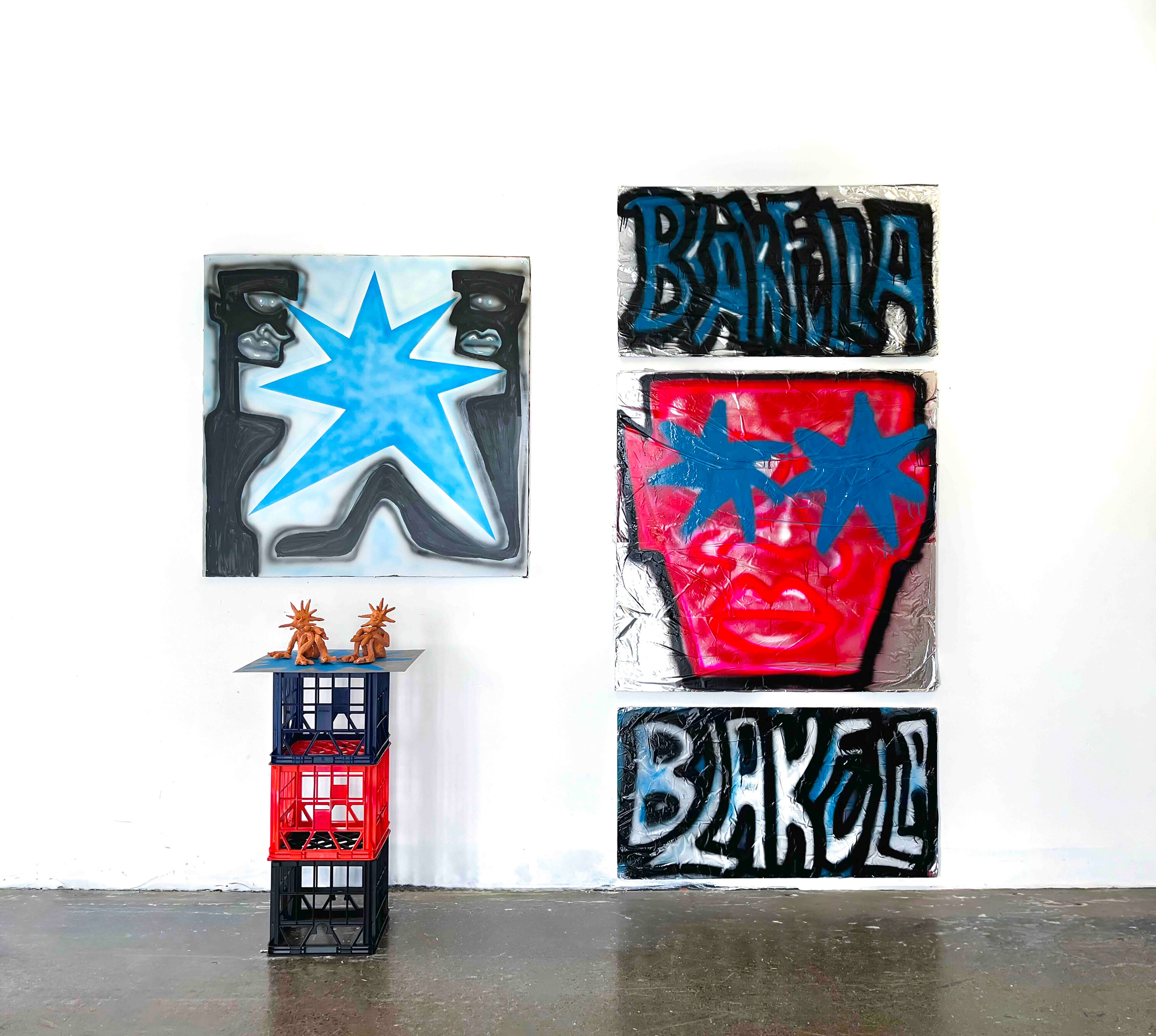

Gosha Heldtz, True Blue, 2024, mixed media installation. Photo: supplied by artist.

Refusing to capitulate to settler audiences hoping for “authentic aboriginal” art, in True Blue (2024) Gamilaroi artist Gosha Heldtz cleverly uses cheap and discarded materials like cardboard and acrylic paint to interrogate how symbols are used to construct a so-called-australia. “BLAKFULLA”—graffitied in bright blue on cardboard—is positioned near the floor, marking True Blue as a strident reminder of Blak resistance through art. By deconstructing the Southern Cross, the very stars used to direct the colonial invasion of Botany Bay, Heldtz asserts that settlers must not follow the beacon towards the colonial constellation but re-route and decolonise.

In one painting, the apexes of the unusual seven-pointed star are elongated until needle-sharp, threatening two Indigenous figures, whose backs push against the border of the canvas. In the foreground, two clay figures lounge on a makeshift milk-crate-plinth. Their heads amalgamate with the Southern Cross, reflecting the violent enforcement of patriotism on Indigenous people. This time the star explodes and the spindles grow spikes, transmuting the symbol into protective armour. Looking at the figures’ lanky stances, I’m reminded of cheeky Mimi spirits. It’s easy to imagine that once the gallery workers go home, they will catapult off the crates and run amok. Protected by their star helmets, they roam freely through the art school, stopping for rest amongst the Xanthorroea at the Central Heart Garden, tended by Tess Allas and Clare Milledge since 2018.

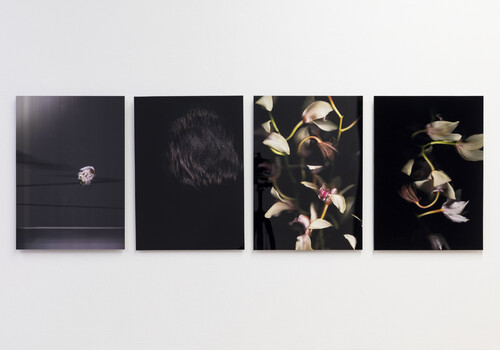

Installation view of Richard Trang, (Un)Familiar Photos, 2024, installation. Photo: Ava Lacoon.

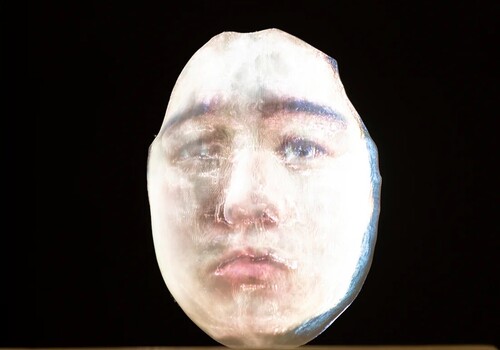

Located in the backroom of UNSW Galleries, Richard Trang’s (Un)familiar Photos (2024), antagonises (predominantly non-Asian) gallery patrons in a game of cat and mouse. The trap: a mise-en-scène of an abandoned family room where a lone teddy bear sits upon a two-seater, looking at a floor-to-ceiling projection of a “sentimental” photo collage from a family archive. Lit only by the bleed of the projection, a dappled portrait lands on the sofa’s headrest, keeping the bear company. Onlookers exclaim at how cute the artist was as a child and speculate about a possible tragedy, while inquisitive eyes ogle the cultural outfits. Yet these images do not depict Trang or his family, but strangers and AI constructions. (Un)familiar Photos trolls viewers who anticipate a minority trauma porn narrative to get off on. Trang thus confronts our current art landscape, where Asian artists are asked to mine themselves for resources and provide unlimited access to their histories and identity.

I walked out of the Annual relieved that graduates are navigating their identities not at their expense, but by maintaining a sense of autonomy, unnerved by the neoliberal university’s pacifying forces.

Ava Lacoon is a (forever) emerging arts writer and curator based on Gadigal Land. She is currently completing a Bachelor of Fine Arts (Art Theory).