Honours, Victorian College of the Arts

By Rose Gertsakis

Bodies, bodies, bodies. They’re everywhere! A metal heart beats on a string, a wilted figure melts over a grind rail, and agar tongues hang tenderly over copper bars. The corporeal has collided with the metallic. Bodies are picked apart, dissolved, coquette-ified and filmed for our viewing.

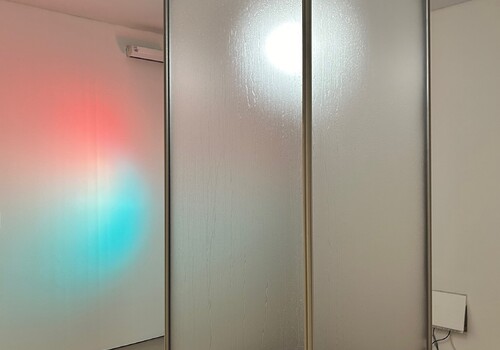

Installation view of Ziyi Wei, The Return of Spontaneous Circulation, 2024, readymade jewellery, alloy, bronze, composite gears, micro DC motor, circuit board, silver, PVC, glass, wire video, VCA, Melbourne. Photo: Rose Gertsakis

One space features a hanging silver heart, titled The Return of Spontaneous Circulation (2024). Bursting with an array of metal trinkets assembled by Ziyi Wei, I initially expected this glinting object to beat spritely. Instead, its ornately heavy florals pulse with a deeper rhythm beyond their beauty. The Return of Spontaneous Circulation seems to succeed at a Sisyphean task. This silver ticker’s hanging bells don’t ring. Rather, the apparatus’ internal mechanics shutter with each pulse. Instead of pushing a boulder up a hill, its metallic ventricles strive to pull away from a heavy centre. Does it want to explode, or remain a sum of its parts? The heart is a muscle, and this one grows stronger as it upholds silvery beauty and a steady beat. Somewhere out there, a futurist tinman with a penchant for the coquettish needs it back.

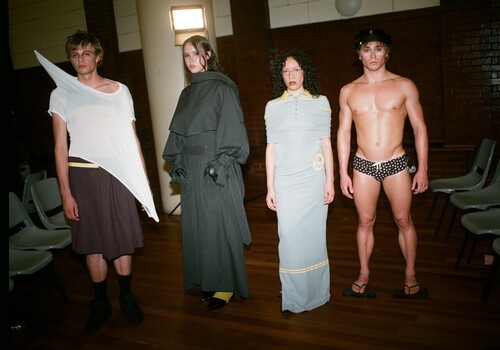

Installation view of Nicole Goode, Linger (Bank Ramp), 2024, performance, VCA, Melbourne. Photo: courtesy of the University of Melbourne

In an adjacent ventricle is Linger (Bank Ramp) (2024), a bright blue, weathered grind rail with no skateboarders or arresting graffiti in sight. In contrast to the usual crunch of a wooden skateboard sliding across this metal, Nicole Goode slithers silently across and around the structure. Goode’s body slowly drapes and drips around the blue metal, in opposition to its stark linearity—it’s easy to get lost in her emanating tranquillity. In the neighbouring stable, an hour-long video of Goode performing the same body-as-metal dance in a skatepark loops. She has become a form of continuity between the two spaces: a magnet drawn toward the metallic.

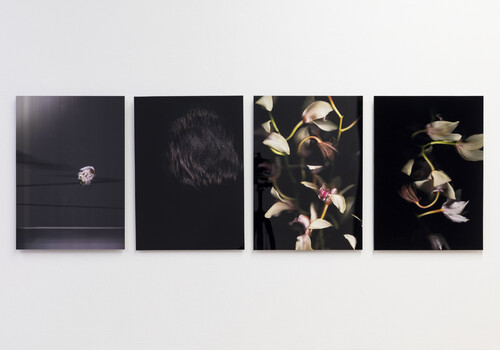

Installation view of Xana Jensson, Anemoia, 2024, copper, wood and agar, VCA, Melbourne. Photo: courtesy of the University of Melbourne

Xana Jensson’s Anemoia (2024) makes me think of roll-ups and warm bed sheets drying outside in the breeze, but most of all, it reminds me of melting tongues. Upstairs in The Stables, a breeze created by walking onlookers works its way through pastel-coloured sheets of transparent agar draped over thin copper bars. Some are pink and smooth, others have honeycombed holes, and another has the imprint of a grid. Dotted around walkways and hung over partitions, no obvious body is present, but there is a fleshy quality to the objects’ materiality and positioning. These sheets of agar could be the next stage in Goode’s reincarnation as melted matter. This time, though, the body has become referenced, inanimate and can only be moved by a coincidental breeze prompted by another body moving past. The word “anemoia”refers to a distinct yearning for a past never experienced, and these somatic forms seem to crave a time when they could move freely, without the support of copper bars.

These artists remind me of my own corporeality, yet they also create a distance, one that allows me to visualise the body in various states of metallic malleability. Does Wei’s metal heart still beat when the lights are turned off for the day? Does Goode fully melt into the metal when no one is looking? Do Jensson’s delicate agar sheets continue to sway when the space is empty? Perhaps. More importantly, though, their melting movements come to be defined by bodies like mine moving freely through The Stables. Their referential bodies seemed so different to mine at first, mirrored on screens, magnetised to metal and seduced by futuristic visions. Pulling my phone out of my pocket to check the time, I realise maybe I’m not so different to the metallised bodies on display.

Rose Gertsakis is a writer and arts worker living in Naarm (Melbourne). She is currently studying a Masters of Cultural Materials Conservation at the University of Melbourne.