Printmaking, Bachelor of Fine Art, National Art School

By Uma Rogers

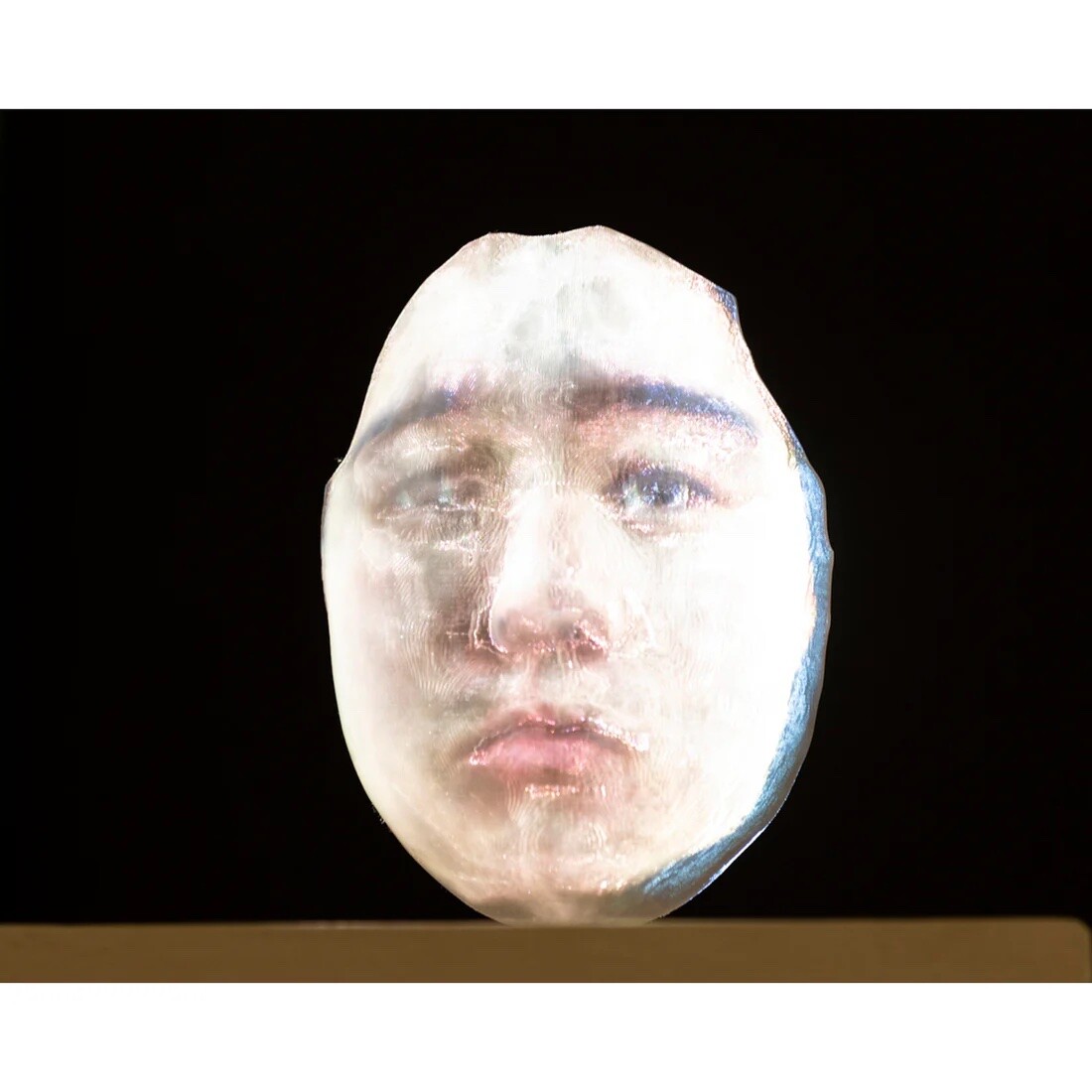

I am weaving through the dense opening night crowd at the NAS grad show when I swear a portrait starts blinking at me. Maybe portrait is the wrong word, although I am not quite sure how to categorise Yuyun Ma’s Face No #2 (2024). Staged on a white plinth, the work is a 3D-printed render of Ma’s face, backlit by a projected digital video of his facial expressions. The overlay of moving image dissolves the plastic mask into a flickering hologram. Searching for Ma’s digital descriptor in the online catalogue, I am surprised to find the work categorised under printmaking.

Yuyun Ma, Face #2, 2024, polyethylene terephthalate glycol (PETG), single-channel digital video, projector, 213.75 x 160 x 82.24 cm. Photo: Courtesy of the National Art School.

In an increasingly interdisciplinary contemporary art environment, NAS’s commitment to the dominant mediums of fine art remains steadfast. At least it appears so from their social media curation. In the lead up to the exhibition, the NAS Instagram was taken over by a matrix of greyscale graduate headshots, categorised under their disciplinary majors. The 2024 graduating class are not just artists: they are printmakers, painters, sculptors, ceramicists, and photo-media practitioners. This labelling reflects NAS’s technical education, sorting students into distinct specialisations. But in a world that welcomes hybridisation, I wonder how useful these traditional identifiers really are. The exhibition might invite us to “celebrate the future of contemporary art.” But is its medium-focused format forward thinking? What does the medium offer in a post-medium age?

Eleanor Harris, Lenticular 4, 2024, lenticular on Perspex, 22 x 21.5 cm. Photo: Courtesy of the National Art School.

Venturing upstairs to the main gallery, I stand in front of Eleanor Harris’s Song on Paper (2024). It is a large-scale CMYK lino cut of a tree and its shadow, printed in slightly misaligned layers. The work has a gentle fuzziness to it – it feels like looking at the landscape through a fine gauze curtain. Hanging alongside, Harris’ Lenticulars 2, 3 and 4 (2024) amplify this haziness through lenticular printing. Viewed straight on, these smaller works appear like photographic landscapes that have been saturated and blurred to the max. Slightly uncanny, they almost trigger that eye-watering squint that comes from trying to bring an image into focus. As I move across the wall, the zig-zag profile of the lenticular lenses generates an illusion of animation. I walk back and forth, and the blurry fields of saturated colour shift alongside me.

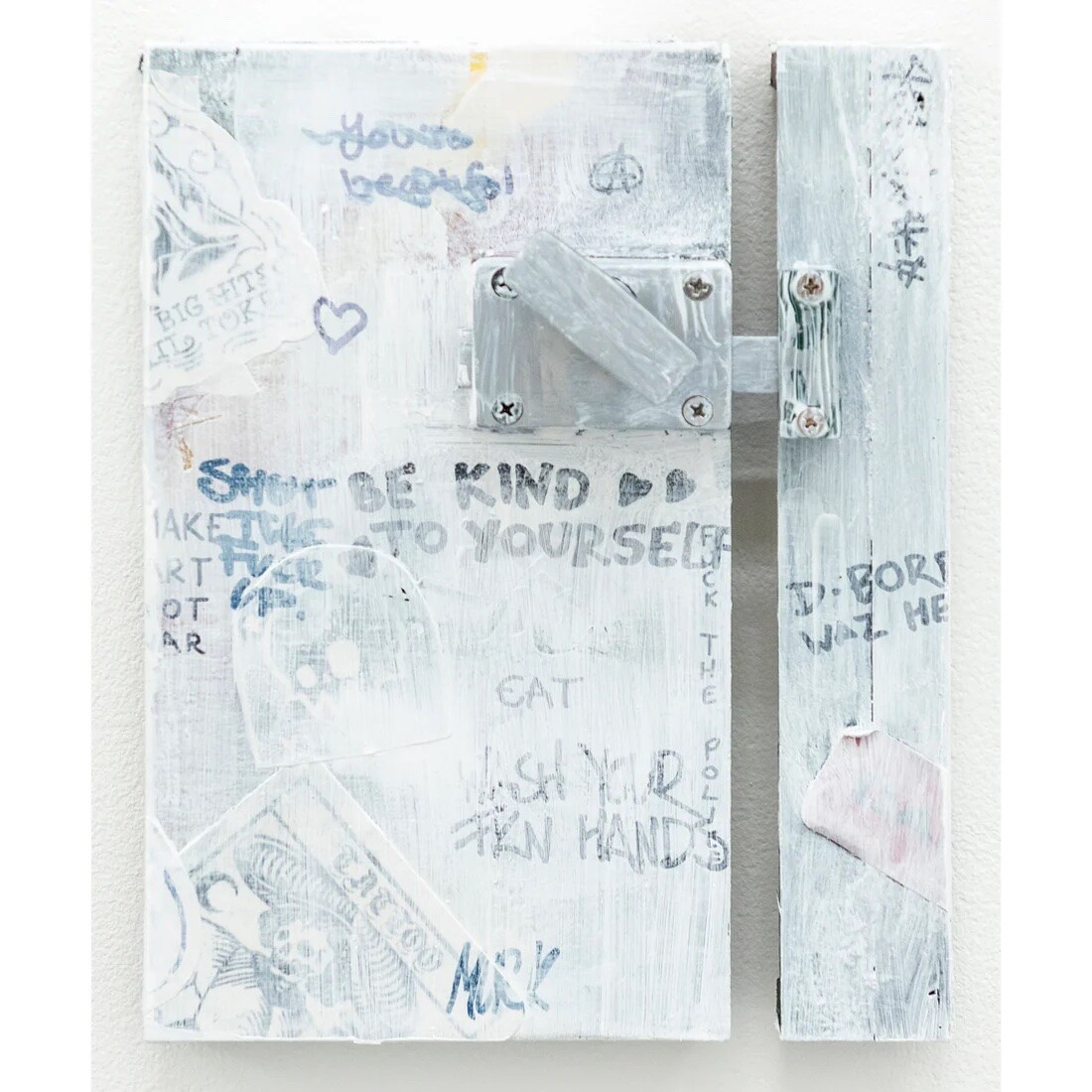

Outside the main gallery, the exhibition sprawls across various artist studios. In an inconspicuous corner of the printmaking room, Karim Fares’ Cubicle (2024) appears more sculpture than “print.” A one-to-one detail of a public bathroom stall, it feels like the object could have been stripped straight from real life. But this work is no readymade. Built up from a plywood base, it is a recreation of graffitied one-liners, scattered stickers, and hastily applied layers of thin white paint. The gritty sensibility of the bathroom stall has been transferred onto the pristine white wall of the gallery. If Harris’ printed lenticular lenses produce an embodied way of seeing, Fares reimagines printing as a mode of thinking. At once intimate and communal, Cubicle celebrates the improvised layers of human inscriptions, spotlighting the confessions, gossip, and casual destruction that is otherwise overlooked.

Karim Fares, Cubicle, 2024, plywood, construction adhesive, acrylic paint, spray paint, alcohol markers, PVA, collected stickers, superglue, public toilet interior locking mechanism, 20 x 24.5 cm. Photo: Courtesy of the National Art School.

As I move from one sandstone interior to another, passing through these architectural thresholds makes me conscious of the boundaries of medium. I start to overcome some of my initial scepticism. Technical training provides a structure and enables the development of skill. But it doesn’t foreclose opportunities to test, transgress, and transform this foundational knowledge. As evident in the blinking portrait of Ma, definitions of printmaking at NAS have been expanded in playful and unexpected ways. The medium is alive and well, but it is not stable.

Uma Rogers is writer working in Gadigal/Sydney. She is currently undertaking Bachelor of Fine Arts (Art Theory) and Bachelor of Laws from UNSW