Honours, Victorian College of the Arts

By Pepa Neralic McPherson

To get a closer look at Georgia Naughton’s paintings, I’m required to traverse a floor of large, loosely secured white tiles, vaguely worried that they will break under my feet. These are the type you might find in a residential kitchen or bathroom. A similar tension and sense of delicateness is present in several standout works in the VCA Honours exhibition.

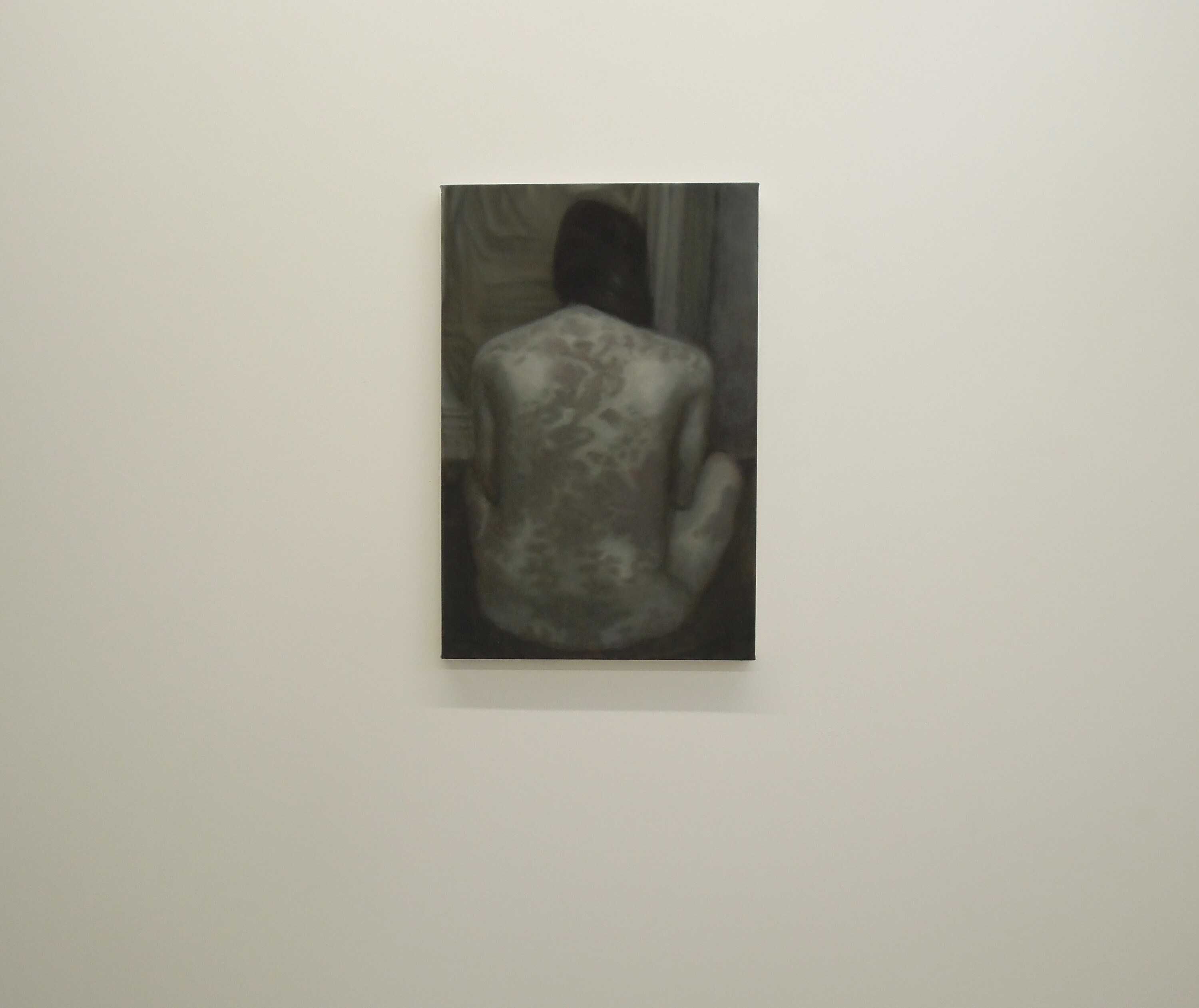

All but one of Naughton’s paintings depict food: most appearing to be sweets. The works have a soft, yet grotesque mouldy quality. The foods themselves are washed-out, muddy versions of their more aesthetically pleasing subjects. There is something uniquely domestic about the kitchen tiles, sweets, and the intimate painting of a back, featuring little purple splotches adorning the subject’s skin, floral but also insidious and bruise-like.

Georgia Naughton, Brick cake gravy and cheese back, 2024, oil on canvas, ceramic tiles. Detail view. Image: Pepa Neralic McPherson.

Further along the gallery is Peta Treble’s Moving My Image Through Any-Space-Whatever (2024). Both rooms featuring Treble’s work seem to mirror each other. Each is furnished with household items: towels folded into swan-like shapes, and cups, plates, and lightbulbs that appear to be readymade; but, on closer inspection, all seem to be crafted in the same dusty, off-white brittle clay.

Both Naughton’s and Treble’s works have a delicate quality. The sauna-like haziness of Naughton’s paintings and Treble’s slightly off sculptures (the craning of the towel swan’s neck and broken handles on the cups) reveal the artist’s hand, signifying a disruption of their originals.

Peta Treble, Moving My Image Through Any-Space-Whatever, 2024, Scupture and video installation, ceramic mugs and saucers, picture frames, door handles, glass panels, double sided mirror contact film, mirrored acrylic sheet, white towels, plaster, steel, wood, black paint, chiffon scrim, 10 minute single channel video, Canon HD AX10 on tripod, livestream projection. Installation View. Image courtesy of the University of Melbourne.

The little white towel swans are slightly dirty, and are the type you might expect to see in a cruise’s honeymoon suite, or perhaps in a more profane invocation: in a porno. This tension I find most appealing in Treble’s work: the simultaneously sensitive domesticity of each work juxtaposed with the bodily connotations of the phallic towel swans, and the breast-like plaster bulbs attached to the wall, stripped of their function and reduced to pure ornament.

However, Treble’s video installation, which occupies the open interstitial space between the two allocated exhibition rooms, is more architectural. The work captures and livestreams the viewer walking around the work, projecting it back on three screens that resemble a room divider. The viewer is forced to engage with themselves like they would a stranger, perhaps narcissistically glancing at oneself while walking through the show. The Mass Memo group visited the VCA galleries for a press viewing alongside donors and benefactors: a strange mix. Another reviewer was asked if this work in particular would “look good in a living room,” unintentionally mirroring the work’s function: to centre the viewer.

Peta Treble, Moving My Image Through Any-Space-Whatever, 2024, Scupture and video installation, ceramic mugs and saucers, picture frames, door handles, glass panels, double sided mirror contact film, mirrored acrylic sheet, white towels, plaster, steel, wood, black paint, chiffon scrim, 10 minute single channel video, Canon HD AX10 on tripod, livestream projection. Installation View. Image courtesy of the University of Melbourne.

Avery Butler’s installation, Children of Camouflage (2024), departs from the lightness of Treble and Naughton’s work. The installation consists of six “rugs,” one silk, identified in the artist contact form as “my Father’s Afghan rug” (although the design appears northern Iranian). The remaining five “rugs” are silver- and black-painted tarp, both rolled and hanging, while a black and white camouflage image is projected on them, echoing their pattern. On the floor sits the sort of mid-2000s laptop you may expect the police or military to use, atop a stout, deployed-type briefcase, evoking a teenage boy’s Call of Duty fantasy. The tiny, hard-to-read text that flashes across a camouflage backdrop appears to tell the story of a young boy whose country is in the throes of war.

Avery Butler, Children of Camoflage, 2024, handwoven silk rug, acrylic on tarp, projection. Installation View. Image courtesy of the University of Melbourne.

The camouflaged tarp is reminiscent of the tradition of Afghan war rugs, popularised online through the ones depicting the 9/11 attacks: a classic trope of safe-edgy internet culture. The tarp takes the very modern, violent symbol of camouflage, and places it alongside the traditional silk rug, which through geometry is made transcendent. Conversely, the tarp “rugs” through the similarly geometric nature of camo attempts to sanctify the modern. Butler’s work has a similar sensitivity to Naughton and Treble, yet through the context of war and military aesthetics, the domesticity of the rug becomes barbaric.

It is this subversion that brings these works together, and what I see as their most successful characteristic. Each artist presents their subjects with a delicate balance between the domestic and familiar, and the confronting. Not too abject, nor too obvious; not too saccharine, nor overly sentimental.

Pepa Neralic McPherson is currently completing her Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Fine Art at Monash University.