Painting, Bachelor of Fine Art, National Art School

By Callum Gallagher

Flesh writhes and wrestles to exceed the limits of the canvas at the NAS grad show. Yet, even as painters push the bodies they represent to extremes—dismembering, excavating, and consuming the soft, wet, tasty, corporeal—these works remain formally contained, despite proffering to represent the uncontainable. But I want more. I’m hungry. Forget the edges of the canvas. Release the flesh.

In Mercedes Vukovich’s studio, I find something to sink my teeth into. A pool of blood contains matted bits of fur. This, along with a bandaged antler Untitled (Roadkill), are indexes of violent dismemberment, and they shock. Excised pieces of dead animal skin line the walls, which Vukovich has reconstructed in the shape of picture frames. One of these works, Incision Piece I, lists its materials beginning with puppy bones? At first, it feels gratuitous, but there’s honesty here. Flesh and bone are not merely represented; they are the materials of the painting itself. Incision signposts a painting process no longer additive but subtractive or extractive. Once whole, the now abject animal body becomes a means for the artist to renounce the limits of the picture. Reconstructed in cowhide, the epidermal surface of the framed canvas is no longer revered: the bones puncture through it. Turned inside out, flesh becomes the border, and skin becomes the internal boundary.

Installation view of Mercedes Vukovich, Incision Piece I, Incision Piece II, Untitled (Roadkill), 2024, mixed media, National Art School, Sydney. Photo: Document Photography.

Mercedes Vukovich, Incision Piece I, 2024, mixed media (puppy bones, wax, cow hide, oil paint, resin), 30 x 35 cm, National Art School, Sydney, https://gradshow24.nas.edu.au/collections/mercedes-vukovich/products/incision-piece-i. Photo: Document Photography.

Next door, a similar aesthetic of attraction-repulsion is found on the painted surfaces of Laura Becket’s triptych, Tablet 01, Tablet 02, and Carthusian. Attraction-repulsion or, as Becket puts it in her bio, “mysterium tremendum et fascinans” plays out across a paradox of depth and flatness. Presented as an altar space, the triptych brings together a fresh dose of minimalism and religiosity. Carthusian monks are silent. So is the painting. Made of a wooden board filled with plaster, the materials are suffocated with a beautifully clear resin skin. The grain of the wood and the cracks where the plaster doesn’t sit flush with it scream out for depth under a silent surface. Meanwhile, the tablets on either side—again, blank shiny surfaces—anachronistically join ye Oldee testament times with a screenic present. Becket seems to lament a lost religiosity of materiality and depth that, while visible, cannot be reached through the two-dimensional surface.

Installation view of Laura Becket, Tablet 02, Carthusian, Tablet 01, 2024, mixed media, National Art School, Sydney. Photo: Document Photography.

Laura Becket, Carthusian, 2024, resin and plaster relief on wood, 120 x 64 x 8 cm, National Art School, Sydney, https://gradshow24.nas.edu.au/products/carthusian?_pos=1&_psq=carthusian&_ss=e&_v=1.0. Photo: Document Photography.

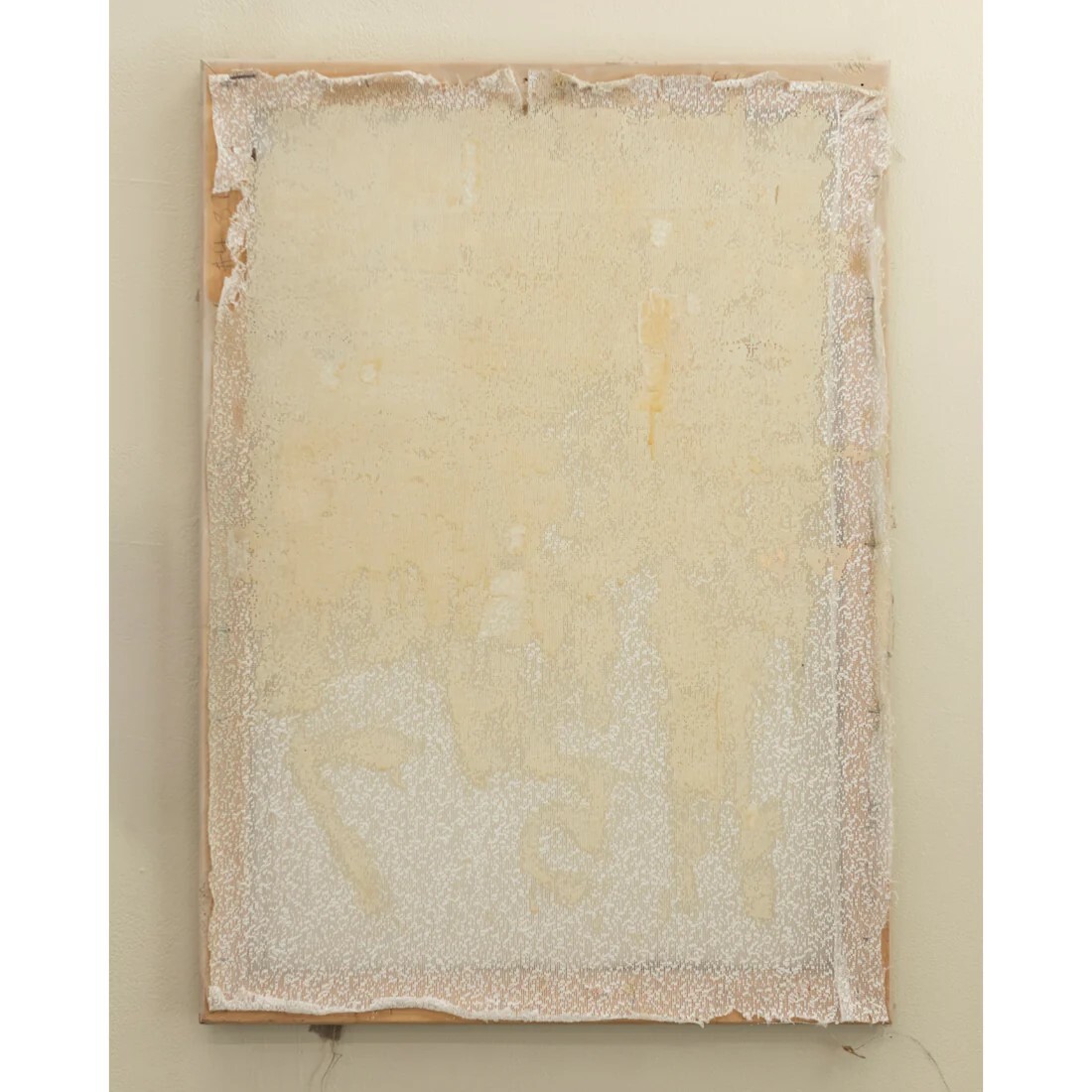

In Francisca Carasco-Reyes’s work situated nearby, this obsession with antagonising the painting’s two-dimensionality continues. In 2170, the surface is thick, gluggy, and opaque. At the same time, it is thin and transparent. Having flipped a timber frame over which canvas should be stretched, Carasco-Reyes approaches it from behind stappling lace-like polyester on both sides, simultaneously imbuing the painting with three-dimensional space as it contains it. Latex clings to this polyester, seeping through from seemingly inside. This is not sexy, shiny latex. Instead, it cloys the fabric, staining it yellow, and recalling skin, sweat, and stench –I can almost smell the ammonia in the liquid latex. Latex is Big Material at the NAS grad show. It’s skin that isn’t skin–that transforms from liquid to solid yet stretches. Carasco-Reyes pushes its bodily connotations with a subtlety compared to others. Their work implicates the body without making it present. As opaque epidermal layers, they acknowledge the flatness of the painting’s surface and all that it represses.

Francisca Carrasco-Reyes, 2170, 2024, latex, tape, acrylic and polyester on timber frame, 88.5 x 63.5 cm, National Art School, Sydney, https://gradshow24.nas.edu.au/collections/francisca-carrasco-reyes/products/2170. Photo: Document Photography.

Painting at NAS is alive, but it interests me most when it is not well. Vukovich’s artist bio quotes Julia Kristeva on how death is generative: “Refuse and corpses show me what I permanently thrust aside in order to live.” Following Kristeva, these artists embrace what two-dimensional painting thrusts aside in order to live—the horror of what is (not) behind its surface. After all, figurative painting is only half-alive, dispossessing reality in order to claim it. In doing so, they grant painting fresh life. Today, the two-dimensional image is also digitally unlimited, and painting must stake an even greater claim for the importance of its limits, even as they collapse. The possibilities of what can emerge from inside the canvas remain–but do we really want them to stay on the surface?

Callum Gallagher is an art historian, writer and casual academic living and working on unceded, stolen Gadigal land. He received a Bachelor of Arts with First Class Honours in Art History in 2023. He is currently curating an exhibition on Australian artist Ida Rentoul Outhwaite at the University of Sydney.