Bachelor of Contemporary Australian Indigenous Art, Queensland College of Art

By Andrew Ruffle

How do you (re)write cultural and intellectual identity when external forces seek to suppress and erase it? This question emerged at the 2024 CAIA Graduation Show, Australia’s only arts programme exclusively for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, boasting alumni including Vernon Ah Kee and Tony Albert.

Leah Floro considers this struggle in a series of five paintings. Floro depicts famous comic book anti-heroes such as Harley Quinn and Batman as outwardly Indigenous Australian people, following a subgenre of Indigenous artists incorporating comic book characters into their work. These Indigenous anti-heroes are placed in ordinary settings, coloured with the palette of the Aboriginal flag. In History, Batman reads a book aloud. But the speech bubble emanating from him is a stark, blank white, void of the black text usually found in such bubbles. Floro highlights the struggle of Indigenous people to have a cultural identity within an environment that has done its utmost to obliterate it. His choice to garb the figures in the clothing of fictional American icons suggests the pressure of further cultural colonisation from abroad. Floro’s paintings present a bitter-sweet optimism. The white ground acts as a blank canvas upon which the Indigenous anti-heroes can inscribe their thoughts, histories, and dreams. But it is upon a whitewashed history that the stories must be placed.

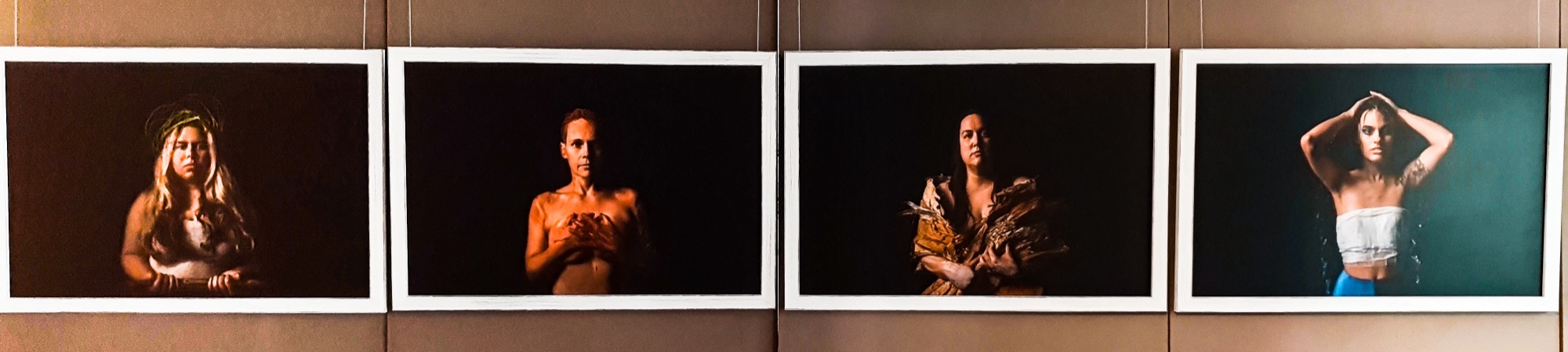

Beth Thompson, Illuminated, photographic print on Fuji Crystal silver halide paper, 90 x 61cm. Photo: Andrew Ruffle

While Floro tackles oppression of cultural and intellectual identity, Beth Thompson suggests Back to Country as a way to reconnect with culture and reclaim it. In Thompson’s photographic series Illuminated, a line of four separate photos contain individual figures, all women, who emerge from darkness. The two central figures wrap and cover themselves in ochre or paperbark, both materials from Country. The women become part of the land. In the Western art canon this may be considered the conventional view of the feminine links to “nature,” though in Thompson’s work it is apparent that it is not just the feminine that is of the land, but the people who are. The outer figures have items introduced to Australia. Particularly interesting is the left-hand side figure holding sugar cane, introduced by the “first fleet” in 1788. The figure holds the cane, appearing to reluctantly accept it, but does not embrace it.

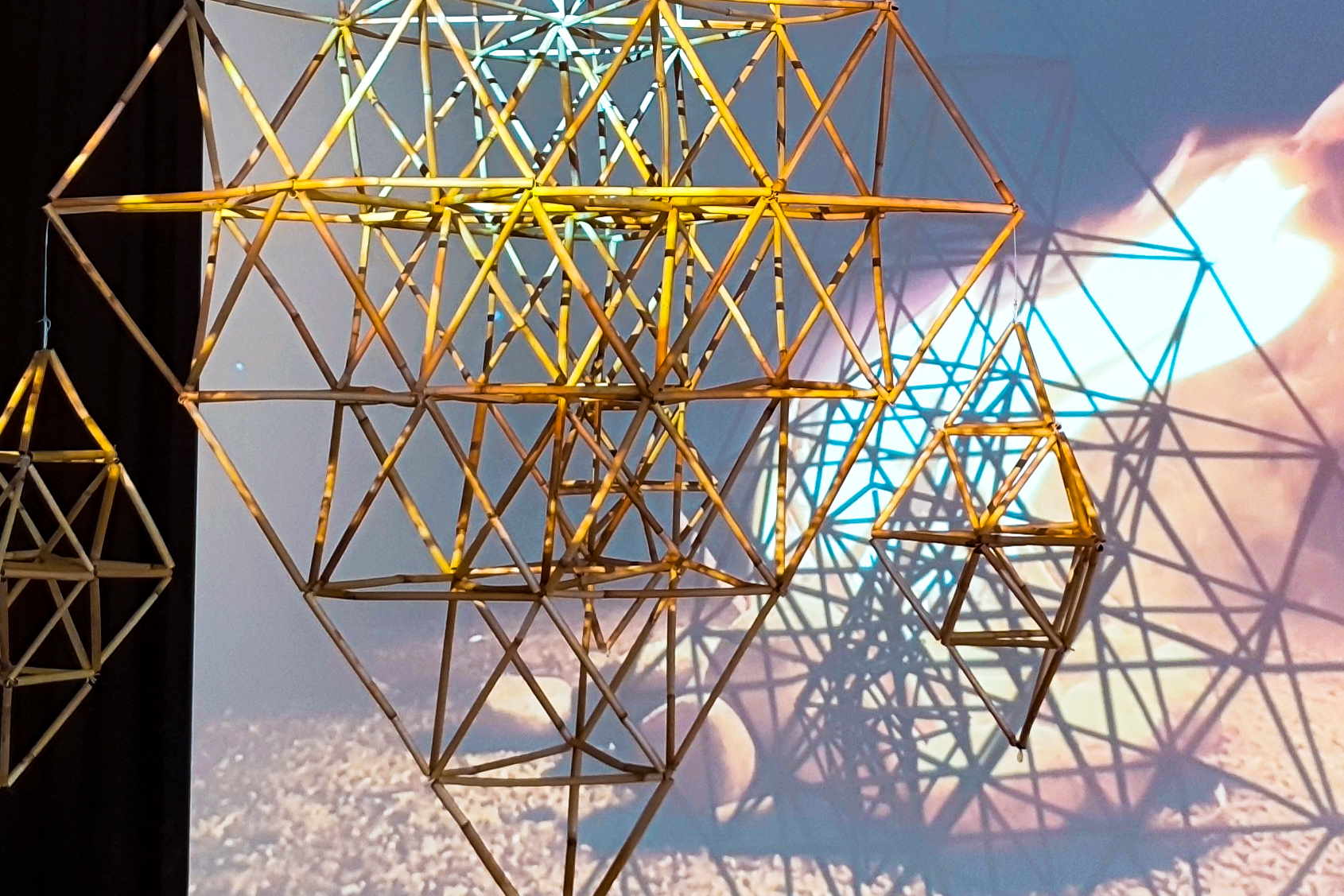

Sarah Zalewski takes a different route still. She examines the creative potentials in embracing both her Polish and Aboriginal identity. Zalewski’s sculptural work Baran-Barahan (Yugambeh for “Spider”) uses Pajaki, a traditional Polish technique that uses material such as straw, dried peas, and feathers to create a mobile. The mobile is “burned to get rid of negative energy,” according to Zalewski. Instead of the traditional Polish materials, Zalewski employs Australian native reed, and cotton (not so native). Behind the mobile, a flame is projected onto a screen. Fire can be seen as uniting Polish and Indigenous heritage. Both cultures have experienced destructive fire raging through them: the Polish during World War II, Indigenous Australians with the violence of colonisation. But Zalewski frames her cultural heritage as resilient, offering hope that, in spite of destruction, identity persists.

Andrew Ruffle is a writer and researcher, recently graduated from the University of Queensland.