Bachelor of Fine Art, Monash Art, Design and Architecture

By Leon Rice-Whetton

On level one, a large air vent is poorly hidden by a partitioned white cube. Hung within this partition are four works by Moss Lasica Wood; inkjet prints, mounted on pine board and then adhered to wall-mounted strand board, each titled with a single hyphen: -. The laminate floor is sticky, mysteriously stained. Perhaps a spill from opening night? On my visit, - (a diptych of two pairs of Levi-clad legs and a late-night image of a car dashboard) had fallen, and was leaning against the wall with a small dent in the corner, leaving the strange texture of its strand-board support behind. A few hours later, Moss was invigilating and had re-attached the print to this support. Chatting to him, he appeared beleaguered by the work, which continued to detach despite his best efforts.

Moss Lasica Wood, -, 2024, inkjet print, adhesive, oriented strand board, 56 x 1.2 x 80 cm; -, 2024, inkjet print, adhesive, oriented strand board, dimensions variable. Photo by Leon Rice-Whetton.

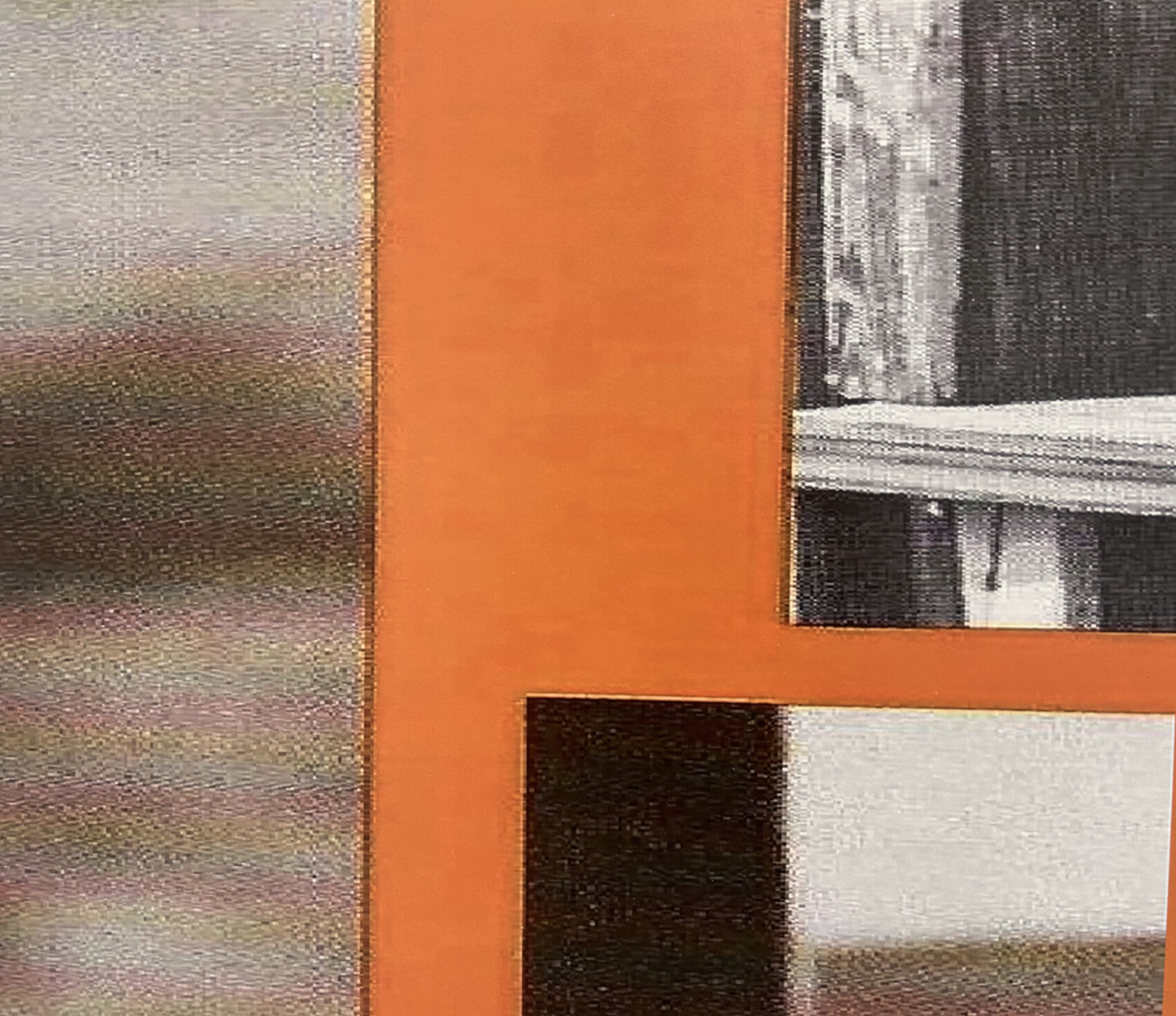

The prints are a disparate collection of imagery—dreamlike, reproduced, hard to discern. Above the diptych is a photograph of a magazine spread of a woman’s cropped face, a digitally flattened paper fold interceding the frame. Opposite this we see a hazy image of a stereotypically Northern Hemispheric winter landscape—a snow-laden pine forest—alongside a digital collage of cropped, chromatically aberrated frames laid against an orange backdrop. This is another flattened illusion, a compressed, pixelated reproduction of a sequence of reproductions.

Moss Lasica Wood, -, 2024, inkjet print, adhesive, oriented strand board, 56 x 1.2 x 80 cm. Detail. Photo by Leon Rice-Whetton.

I lean in close, trying to determine if these are genuinely low-resolution or a high-resolution simulation. Beyond the engorged pixels I can just discern a series of very tiny dots, which could be grain or the dots of an inkjet printer. There is a resonance here with Thomas Ruff’s jpegs, or Hito Steyerl’s poor image, the “lumpen proletarians” of contemporary visual culture—images downloaded, manipulated, and re-exported, leaving pixel artefacts as traces of their networked provenance. But perhaps these references are somewhat dated. Steyerl and Ruff responded to a period where resolution was a contested space, challenging what was lost, or gained, through lossy digitisation. Today algorithmic compression has all but succeeded, becoming functionally invisible. The avant-garde of digital imagery lies in hyper-resolution, where neural networks hallucinate additional visual information to make up for the “failures” of optical capture, imparting more detail than available through our own poorly resolved corporeal reality. What, then, to make of such consciously low-resolution images within this? Is such pixelation little more than a nostalgia for mid-noughties aesthetics?

Moss Lasica Wood, -, 2024, inkjet print, adhesive, oriented strand board, 42 x 1.2 x 30.5 cm; -, 2024, inkjet print, adhesive, oriented strand board, 80 x 1.2 x 46 cm. Photo by Andrew Curtis.

Moss’ images do recall the “vision” of generative AI, associative nodes from a visual cultural melange that, fed the right prompts, could resolve into a high resolution simulation of what it believes we want to see. But instead the prints are left unformed, snippets, imperfectly resolved and compressed, adhered with difficulty. Moss may loathe for me to mention the details of the support structures that fail to remain hidden, from the lost adhesive to the unwashed floor, but like the partition that barely conceals the vent behind it, it is within these failures that the magic of process and the curiosities of supports reveal themselves. Details, intended or not, abound across the memetic and material content of these prints, accentuating a form of truth that a pure lossy mimicry could never meet. Leaving the space, I mistakenly flip my not-so-empty coffee cup and a few drops spill out, adding to the stains and traces on the floor.

Leon Rice-Whetton is an artist and writer from Naarm.