Bachelor of Fine Art, Monash Art, Design and Architecture

By Jessica Wedding

Through their sculptural works, Aliza Nickle and Mia Bell show us how minimalist aesthetics can sublimate maximalist quantities. In a world of excess and overconsumption, Nickle and Bell reveal how a simple yet intentional ordering can organise vast quantities of parts into a single object.

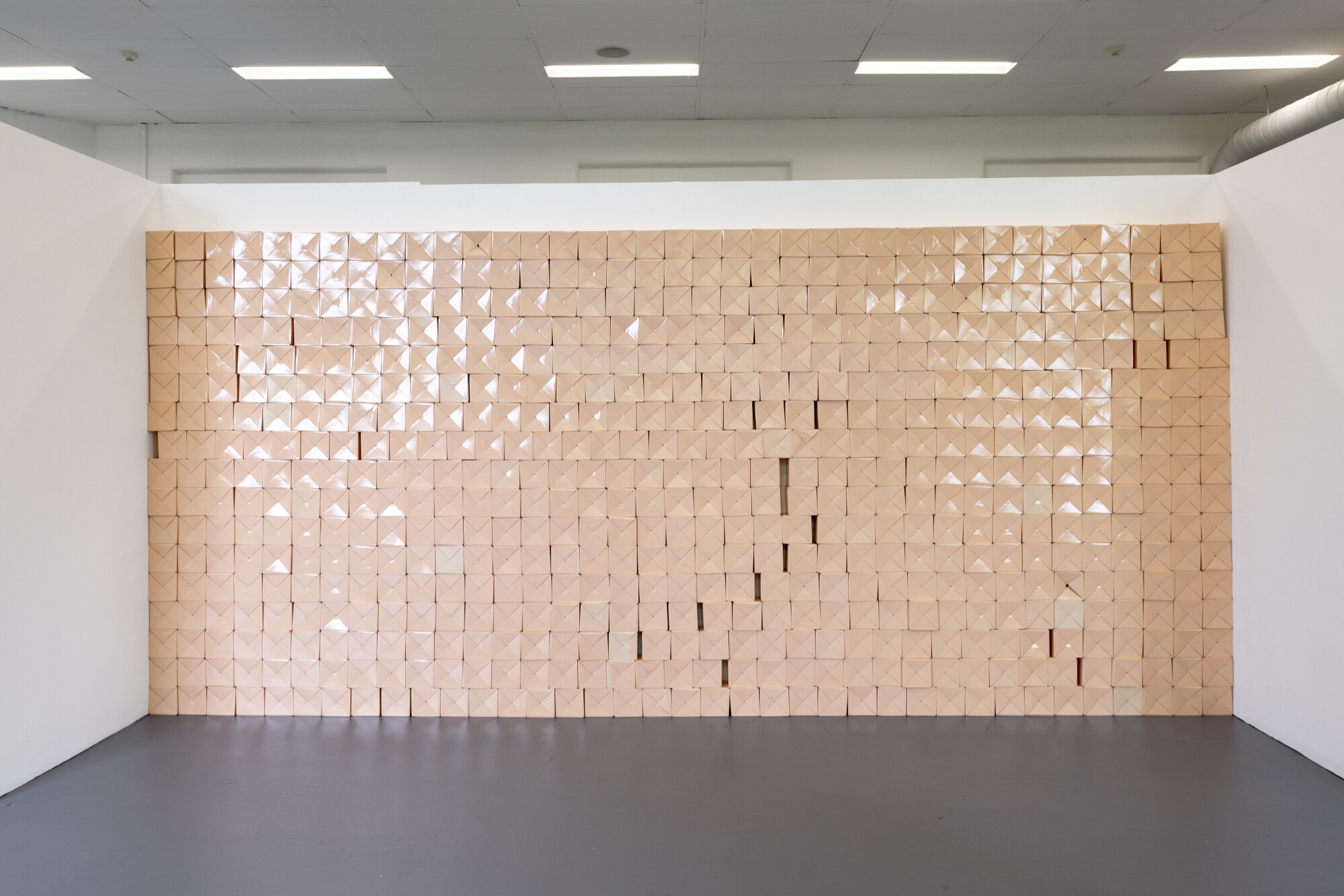

Mia Bell, Box Odyssey: Black harmony wall, 2024; Box Odyssey: MaxFactorX, 2024; Box Odyssey: Ecstasy mirror, 2024. Manufactured boxes. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

Bell presents four large-scale sculptures: Box Odyssey: Pink harmony wall (2024), Box Odyssey: Black harmony wall (2024), Box Odyssey: MaxFactorX (2024), and Box Odyssey: Ecstasy mirror (2024). Each is comprised of hundreds of mass-produced cube boxes about fifteen centimetres squared in glossy black and pastel pink, each hand-placed to produce large, minimalistic structures. Box Odyssey: Pink harmony wall spans a two-by-three-metre-long wall in the middle of the space, the boxes following the length and height of the wall. Similarly, Box Odyssey: Black harmony wall stretches across the opposite wall below the room’s windows. Box Odyssey: MaxFactorX is a spiral-like tower of black boxes beside Box Odyssey: Ecstasy mirror, a knee-height arrangement that resembles a small well. Each box has been placed slightly imperfectly, and some are faded from sun damage. You can imagine Box Odyssey: MaxFactorX teetering towards collapse while Bell precariously balances the boxes while atop a ladder. The odyssey of the production of these sculptures is clear, bringing to mind the precarity and ongoing crises of global capitalism.

Mia Bell, Box Odyssey: Pink harmony wall, 2024. Manufactured boxes. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

Materially, each box replicates consumer product packaging, and through this lens Bell’s work could be considered a comment on the sheer excess of capitalist consumerism. I imagine Bell bulk-ordering the boxes and spending hours constructing them, just like a business owner using the same boxes to ship products to customers. Like Bell’s boxes, Nickle neatly stacks plastic industrial jugs in her sculpture 40 containers (2024), stripping back an auxiliary consumer product to its bare formal qualities and considering its relationship to capitalist flows of goods. Behind this is Nickle’s Cabinet (2024), a discombobulated wooden cabinet stripped back to its raw materials and formed anew.

Aliza Nickle, Cabinet, 2024, 1670 x 840 mm. 40 containers, 2024, 2000 x 1800 mm. Inheritance (1), 2024; Inheritance (2), 2024, Galvanised steel, enamel paint, stoneware ceramics, 1800 x 1200 mm. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

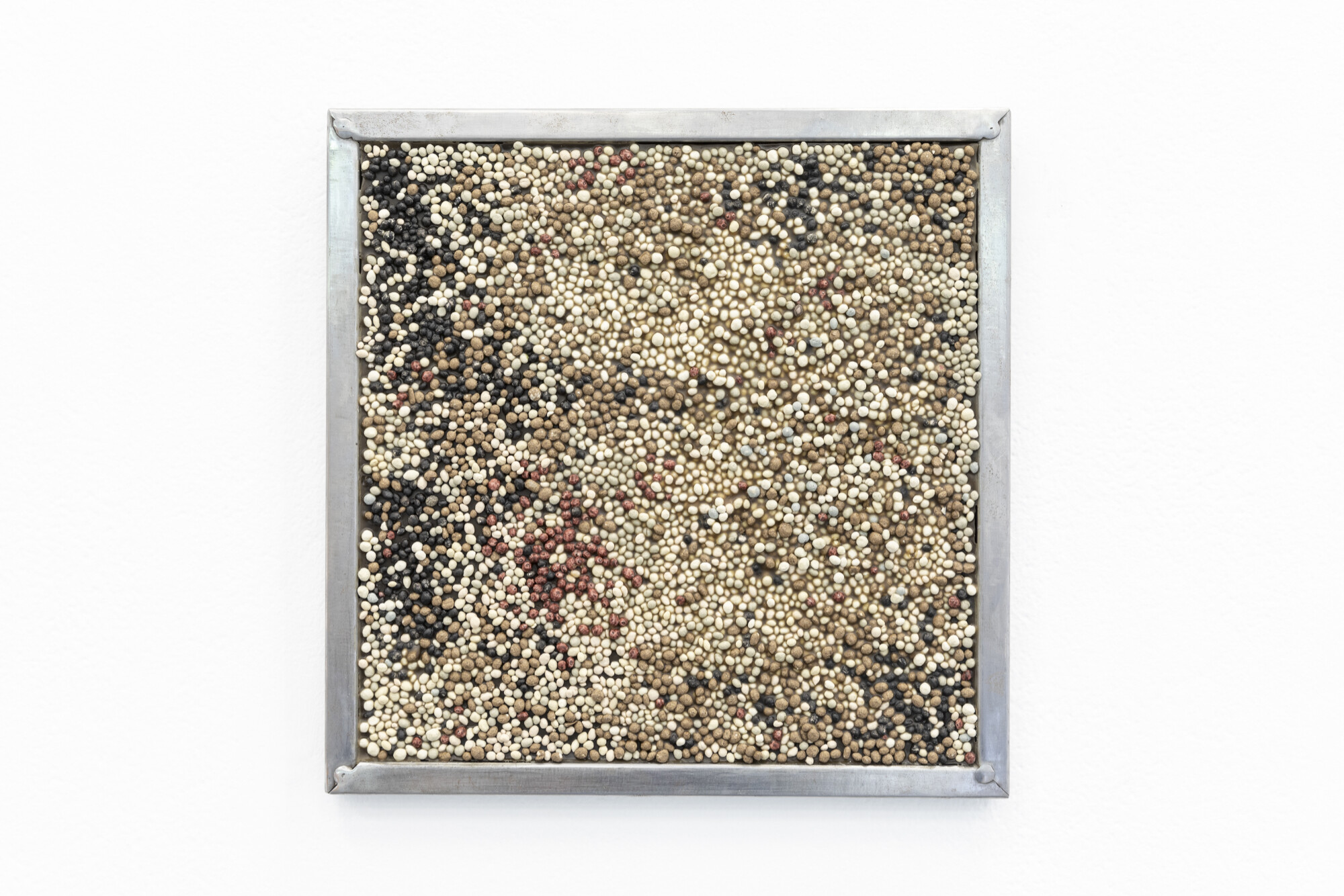

On the other hand, Nickle’s excess in Inheritance (1) (2024), Inheritance (2) (2024) and Inheritance (3) (2024) is connected to an actual product—the hand-rolled natural clay beads her grandmother made for her small business, which I heard about through a conversation with Nickle. Inheritance (1) and Inheritance (2) feature two large red enamel panels gridded with brown clay beads, each surrounded by a small white circle like a halo. In Inheritance (3), clay beads are set in wax in a steel frame. On closer inspection, the subtle imperfections of each bead become visible; each was mindfully rolled by hand—another odyssey of a task. Additionally, as with Bell’s boxes, this action recalls a small-business owner producing objects in bulk while maintaining traces of human touch.

Aliza Nickle, Inheritance (3), 2024. Steel frame, wax, stained stoneware ceramics, 240 x 240 mm. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

The effect of these works is a sublimation of individual objects into excess. Despite the individuality of each bead, box and container, the mass-ordering approach Nickle and Bell use diminishes that individuality, and they become part of an abundance. For me, this points to how products, information, and even art have become part of an abundance within capitalist globalisation. These objects—particularly art—have partially lost their sacredness, and become part of the excess to which they belong. While perhaps a cynical thought, it is a creatively generative one for Nickle and Bell, culminating in a collection of captivating works.

Jessica Wedding is an emerging writer and curator. She is currently studying Arts and Art History and Curating at Monash University.