Bachelor of Fine Art, Monash Art, Design and Architecture

By Charlotte Renfrey

Memory, light and time: three intangible concepts that San Nhi Chung, Georgia Braam and Vikki Chung render tangible in the MADA grad show. Somewhat frustratingly, I found them to be a confronting reminder of the relentless passing of time and the fallibility of memory.

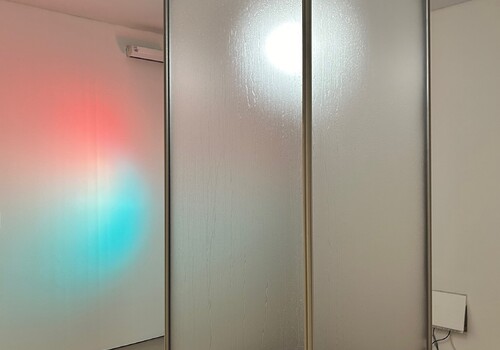

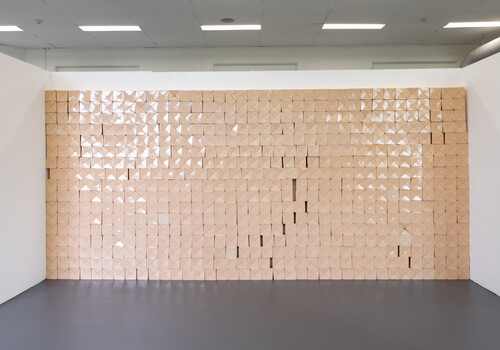

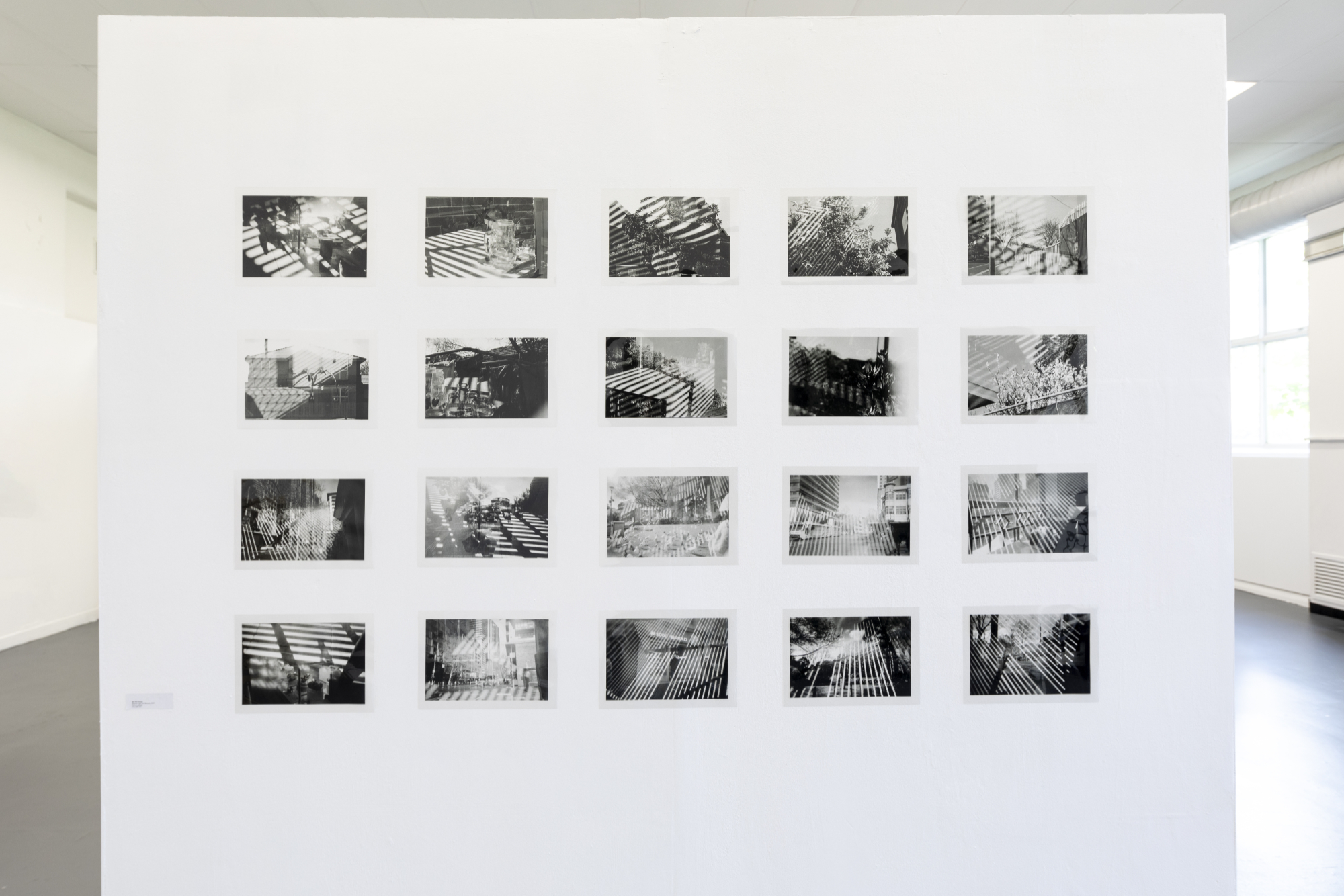

The twenty prints of San Nhi Chung’s Between Light and Memory each depict images of what I imagine memory to look like: hazy and incomplete, and distorted by converging images. My vision is impaired by the glare of the light that Chung layers over each of the images, as though sunlight has poured through nearby shutters. With this series Chung reifies the impermanent, in the form of both memory and light. Upon closer inspection, I can see the grainy gallery wall through the printed acetate and, stepping back, my own reflection. Perhaps Chung has allowed me to see multiple moments in time. It is as though this layering of visuals is a nod to the transportive nature of memory, taking us one place while we stand somewhere else.

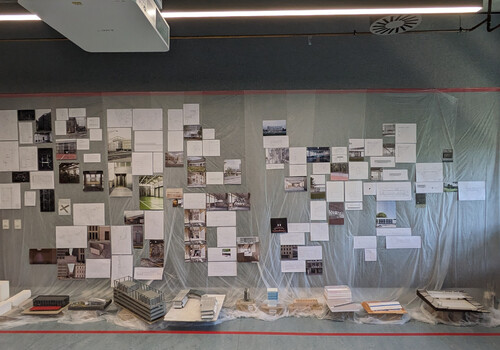

In the comfort of a beanbag chair, a relic of most of our childhoods, I watch Georgia Braam’s video work, Untitled. It shows a house, covered in the projection of childhood videos. While the footage is personal to the artist, the nostalgia of a childhood home imbued with the milestones of youth is recognisable to most. The slight swaying of the mobile hanging on the veranda pulls me out of the footage, reminding me that I am witnessing two moments in time. The footage, warped by the contours of the house, is perhaps as distorted as our childhood memories. The other works of Braam’s in the show include stills of the video: two prints, and a book titled Photobook Evidence. But the video work particularly resonates. Its clear projection on the gallery wall contrasts against the warped recollections projected on the house. I can feel a distinction between the contorted childhood memories and my present moment in the gallery.

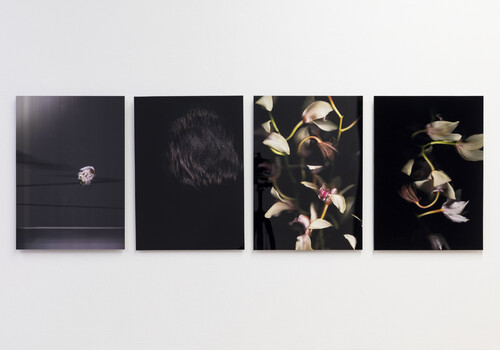

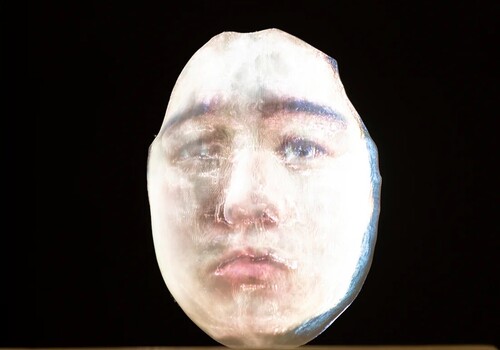

Vikki Chung’s Frozen appears as a desperate yet failed attempt to freeze time: a clock solidified in resin that continues to tick. While visually contrasting against her neighbouring oil-on-canvas works Stray (1), Stray (2) and Stray (3), their joint exploration into the transience of life bridges this difference. I can see this in the surrealist nature of Stray (1) and in the Vanitas-style still life of Stray (2). Extending beyond the irony of the clock continuing to work, Frozen also prompts me to reckon with my own mortality. Knowing that the batteries sustaining the clock are unable to be changed adds an element of memento mori to the artwork. However, like those insect specimens solidified in resin for eternity, the clock even after its “death” will stay preserved as a reminder of the passing of time.

With my discomfort also came reassurance. Whether it was spotting my own reflection or the swinging of the mobile or the clock ticking, I remained anchored to the present. Reminding me that perhaps the passing of time can be transcended by the complex dance we enact between our memories and the present moment.

Charlotte Renfrey is an art writer and emerging curator based in Naarm/Melbourne. She is currently undertaking a Bachelor of Arts and a Bachelor of Art History and Curating at Monash University.