Bachelor of Visual Arts, Sydney College of the Arts

By Josie Witherdin

Artists have become as slick and sophisticated as the finance bros. The Sydney College of the Arts does not appear to be the underground, smudged-up site of identity crises and charming debauchery any longer. In fact, if I weren’t reviewing it, one could convince me this is not a grad show at all. The refined exhibition design and accompanying works exude a carefully resolved professionalism. Polished, sharp and promotional. Is this a requirement or a provocation for being a “New Contemporary?”

In the first-floor corridor, Aneka Jones’s Rotten (2024) offers us the soaking wet flesh of her undergraduate degree in the form of a self-portrait. Simultaneously repulsive and sympathetic, the work is comprised of two oil paintings on canvas: one depicting a dead piglet branded “ROTTEN,” the other, an extreme close-up of the tip of a penis.

The tip is never usually the feature of the dick pic, but centred here with its waxed and glossy opening, Jones dares me to look a little closer. In the didactic, Jones identifies the capacity for this opening to index an exit and entry “for love, for pleasure, for life, for waste, for violence.” Similarly, the piglet assumes an oxymoronic sensibility. Young in age, it signifies the promise of an unknown future, only to be quickly contradicted by its premature death. As the penis and piglet coalesce, a beginning and end materialise. Commodity and re/production collide in a violent stillness. The detritus: meat, masculinity, labour, and profit. As a “self-portrait” of a university educated artist, Rotten implicates Jones into the orgy of commodity re/production. To some extent, it seems we are all getting fucked by our tertiary institutions.

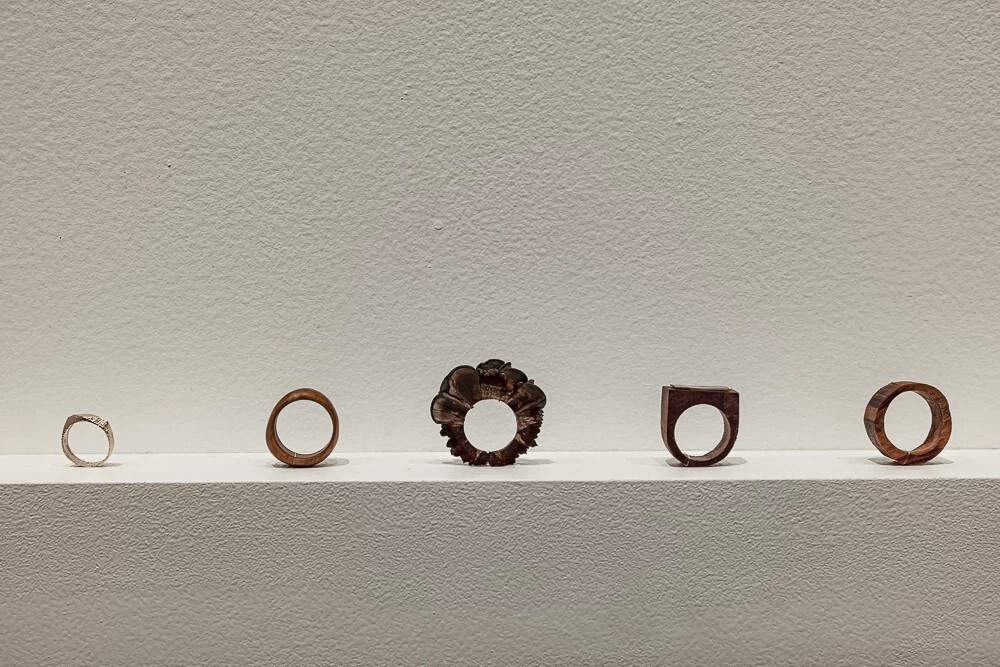

In Chloe Burton’s A Ring A Day (2024), sixty-six unique rings document the iterative and cumulative process of an “emerging” artist. Glass, wood, soju bottles, and bronze represent a small cross-section of the materials Burton manipulates into individual pieces of jewellery. Displayed on a long gallery shelf at chest-height, this work beckons closer examination.

Inspecting for differences and similarities, I begin meditating on the recurring circle. Rings tracing the life of trees, or the “O” of a shocked mouth that’s just caught some gossip. Typically, at art school, “You are going in circles,” and in Burton’s work, it is encouraged. Burton posits artmaking as an intentional practice; like cementing any new habit, this practice must be moulded and repeated over time. What emerges is a tactile and wearable chronicle of selves that Burton fine-tunes. If an SCA graduate were to gift us their diary, this work is what we would see.

While Burton investigates the site of the individual through accretive work, Shelley Watters recentres the process of collective care in the era of hyper-individualism with her sculptural, audio, and print work Entangled: Bulanaming (2024).

The installation comprises three discarded ironing boards transformed into mobile gardens of community-gifted non-native plants. On the opening night, Watters distributed seedlings from the Sydney Turpentine-Ironbark Forest Ecological Community to exhibition attendees. As participants plant their take-home seedlings, they are encouraged to log its photo and location on the artist’s website. Forming a digital network or rhizome, disparate communities of plants and humans lapse into a nexus of care. Watters thus queries how we might care within (and beyond) the constraints of tertiary institutions, gallery walls, and profit-driven hyper-individualism. As the work comes to fruition through exchanges between strangers, Watters offers us another definition of being a “New Contemporary”: creating in common.

Leaving opening night, I fantasise about planting my seedling in the backyard of my student sharehouse. And then I remember I live in Sydney. I can’t afford a backyard.

Josie Witherdin is a writer based in Gadigal/Sydney. She holds a Bachelor of Fine Arts (Art Theory) from UNSW Art & Design.