Master of Architecture Design Studios, Monash Art, Design and Architecture

By Lily Di Sciascio

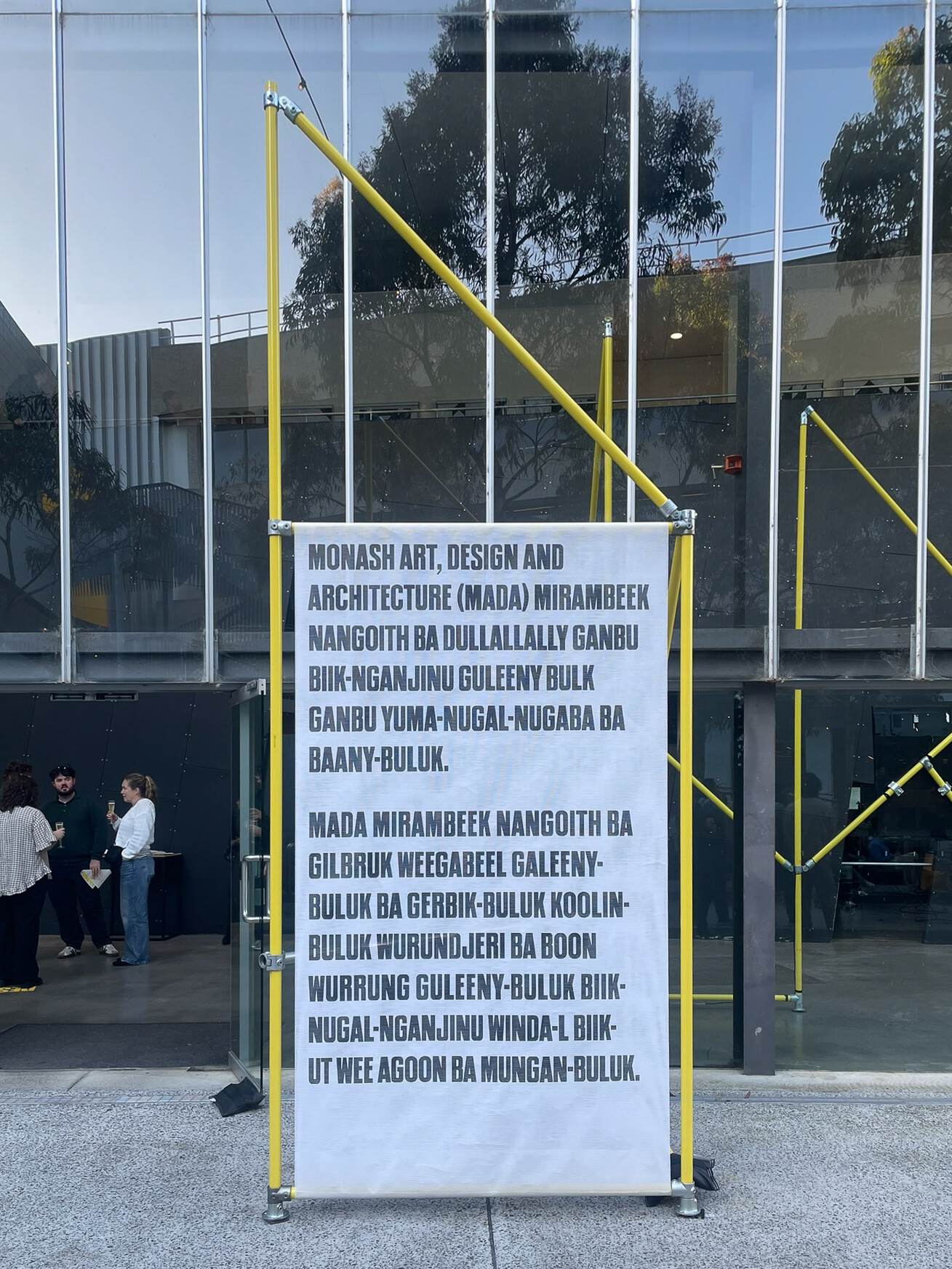

Creativity with Purpose is the MADA Now 2024 theme, signified by a sculptural structure at the entrance of Building G. The yellow scaffold system and accompanying pamphlet give the exhibition a sense of entry, foregrounding student work with the school’s belief in the “transformative power” of design to address the issues of our time. It is busy on opening night: families potter, a bit lost but finding their way; groups of friends rush about, comparatively sure of their direction, regaling in the culmination of another semester. I make my way across the raised walkway to Building F, up to Level 3. It is hot, the air heavy from the day, made thicker by rooms at capacity.

Entry to Building G, yellow scaffold system. Photo: Lily Di Sciascio.

Creativity with Purpose pamphlet. Photo: Lily Di Sciascio.

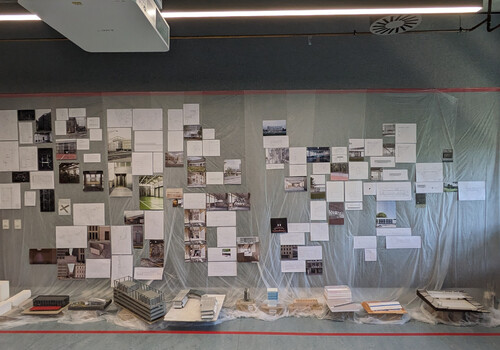

Graduate exhibitions often display the tensions over authorship and control between institution and department, department and tutor, tutor and student. Within the mess of university politics, and the requisite pedagogical and representational biases, the centring of the student/s and their learning can be lost. The strength of the MADA Now graduate architecture exhibition is in the studios taking clear positions. Whether in representing as a collective or prioritising the individuality of the students’ outcomes, clarity of narrative was present across most of the eleven studios.

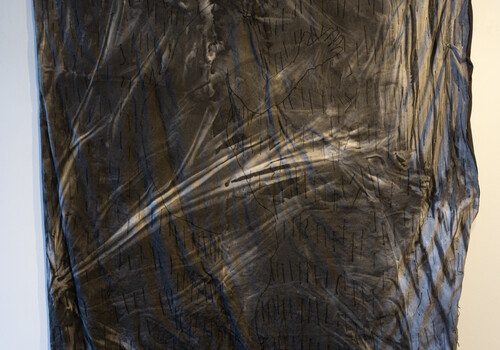

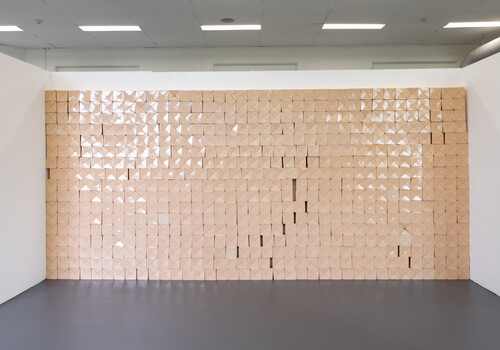

Groundwork (Negative Positive), led by Ross Brewin. Photo: Lily Di Sciascio.

Groundwork (Negative Positive), led by Ross Brewin. Photo: Lily Di Sciascio.

Ross Brewin’s Groundwork (Negative Positive) studio celebrates collective authorship and design process with real-world application. A collaboration with Millie Cattlin and Joseph Norster of These are the Projects We Do Together, the “design-make” studio produced a sensitive, whole-class-designed gathering space and rehabilitation proposition for The Quarry, sited on Gadubanud land. The exhibition is a clear unfolding of the semester, exploring themes of material reuse, sensitivity to place, and designing for constructability/disassembly. Case study models and site visit explorations ground the project in process. A 1:1 prototype of the “positive” proposition, along with rocks and natural materials from The Quarry, gives the site and the project presence within the exhibition space. People are sitting on it, there is a forgotten drink on the besser blocks. An object designed for gathering, in use.

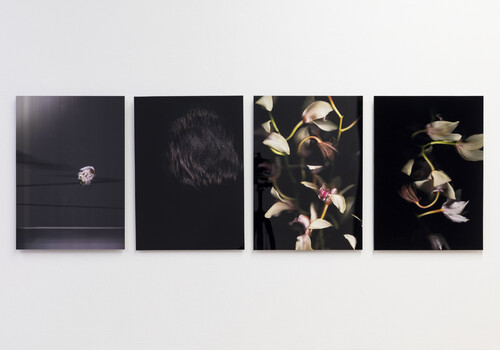

Eduardo Kairuz’s studio Fugivity critiques architecture’s engagement with social and climate justice. Where Groundwork invited visitors to engage with their collective design output, Fugivity asks visitors to add their thoughts to butcher’s paper applied to the surfaces of the darkened exhibition space. A collection of mirrors is clustered in the centre of the room. Light is cast upon them by a projector, refracting circular beams across the four papered walls. A small collection of posters describes the complicity of the profession, illuminating the spatial and architectural qualities of Israel’s ongoing illegal occupation of Palestine. On one wall reads, in large letters, “FREE PALESTINE, FREE LEBANON, DONATE HERE.” I can’t find a code to scan on the day – I later learn from a student that the university required it to be removed. A screen in the corner phases through student work, propositions for architectures of resistance, such as Sree Arun’s Parudeesa. An allegorical representation of “the tensions between resistance and colonial persistence” within the context of British Imperialism in India, the project is graphically strong and full of feeling. Rather than a retelling of a semester, the studio is an invitation to sit with the discomforts of a profession embedded within systems of tyranny and exploitation. It feels radical and conversational: the spatial embodiment of an ethic for students to bring forward into practice.

Fugivity, led by Eduardo Kairuz. Photo: Lily Di Sciascio.

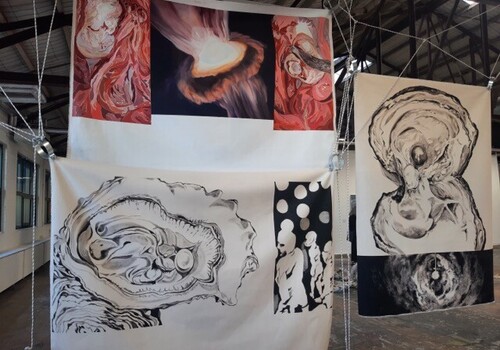

Together Apart, led by Lee-Anne Khor, Shane Murray and Karl-Heinz Weiss. Photo: Lily Di Sciascio.

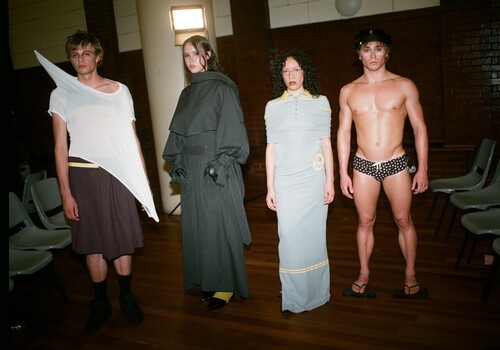

In a well-lit room further down the hall, Lee-Anne Khor, Shane Murray and Karl-Heinz Weiss’ studio Together Apart explores the delivery of efficient and quality social housing within the complex landscape of Sydney’s housing supply. In mimicking a domestic space with all the requisite paraphernalia, the exhibition design is made to feel collective. The spatial qualities of domesticity are foregrounded, with dimensions made visible, and a deliberate circulation path laid out for visitors. Individual student efforts are celebrated and accessible; panels are hung on a clothes rack, inviting people to engage with the work more intimately. A QR code links to a studio website showcasing the individual student projects. Anna Nasioulas’ The Facet Formula stands out, proposing clustered apartment blocks that offer residents optionality within a standardised plan. Connected via external walkways, ensuring daylight access and cross-flow ventilation for all apartments, the design meaningfully considers amenity across scales.

Each of these studios speaks confidently to their agendas. Students have explored diverse narratives, with themes embodied not just graphically but spatially within the exhibitions, inviting visitors to enter, engage and reflect. There is care here, in the work, and in the tailoring of the programme. This diversity in outcome and expression is honourable, given the flawed process of navigating productive tensions within the confines of institutions like universities.

Lily Di Sciascio is a student of architecture in Naarm with a background in anthropology. She has an interest in the intersections of design, culture, politics and marginality.