Painting, Victorian College of the Arts

By Gemma Topliss

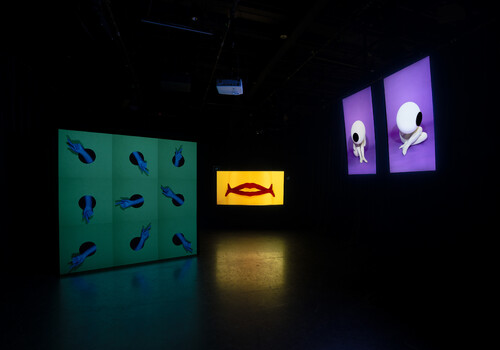

Eat, shit. Ignatz Cady Freer (one of the co-founders of the currently hibernating Wethouse) presents a body of work at the VCA graduate show, replete with mouths, tongues, digestive tracts, genitals, wombs and shit. The paintings consume. Let’s begin at the point of ingestion, with Feigling und Pfefferminz liqueurs. Feed is pumped down the throats of geese; Foie Gras (2022) can be pumped down the throat of some grad show gourmand. The mouth not only ingests but also sucks and licks; oral sex features in Sprocket (2022).

The liquor is starting to hit. Your reviewer feels intoxicated. Virgil’s Lean (2022), is a painting that reaches out from the wall, a tongue-like gutter or slide. We descend down the oesophagus and into the guts. Aptly, we begin with a big toe, evoking “bottom-up processing”, a psychological term denoting an immediate bodily response to “sensation” such as stubbing your toe. I’ve also read that feet are such a common fetish because the sensory part of the brain that processes the foot is located next to the area that processes stimulation of the genitals. Wires cross. On the way down the Virgil’s Lean tract we pass Kermit, a throng of outstretched hands and a spectacled woman with another open mouth before descending into the pits of hell. At the base of the painting, human figures languish in eternal fire.

In the stomach of Freer’s work there are remnants of local sustenance, most obviously in the form of Zac Segbedzi and Hamishi Farah’s figurative paintings. International nutriments Jana Euler, Mathieu Malouf and Martin Kippenberger also churn. In the womb painting, Pfefferminz (2022), there are allusions to the consequences of excessive consumption, medical illustrations of Foetal Alcohol Syndrome. Finally, what we’re left with is shit. This is not a value judgement—I mean shit as in the totality of all of Freer’s corner. His paintings are processed goods, whether German spirits or American Apparel casting couch-esque amateur erotic images. They began as consumption, were digested and metabolised, and finally expelled into the gallery.

If Freer is the digestive system, then in contrast, Will McIntyre (another Wethouse co-founder—the third is Margarita Kontev) is the disembodied system of spirituality. McIntyre has built a rock-climbing structure, Wall (2022), that leers over its audience. Is it a shelter or a threat?

Multi-coloured plastic climbing rocks are screwed into the timber panel facing the floor. A pink crystal, rose quartz, rests on the scaffolding of the structure. Underneath the rock-climbing façade is a small Persian rug. Its humility evokes an ascetic lifestyle, or is it the accessory of an aesthetic one? If you were to kneel in prayer on the rug, the top of the wall would dominate you. The construction of the work seems to imply an encompassing of the participant in an act of spiritual 69-ing. Yin and yang.

On the reverse, instead of the leaning cliff, we are faced with a slope or slide. Sharp ends of screws protrude. On the screws, McIntyre has crucified paper and drawings. One is a print-out of the exposed underbelly of a wrist and forearm with an IV drip. Over the top of the image in blood red scrawl are the words “GRETA THUNBERG”. Something about direct IV into the veins of a climate-crisis-radicalised child prodigy makes me think of Swedish-brand Kool Aid. Cult-like tendencies are everywhere in our culture: indoor rock-climbers share the same fanaticism as climate activists, climate deniers, and New Age crystal buyers.

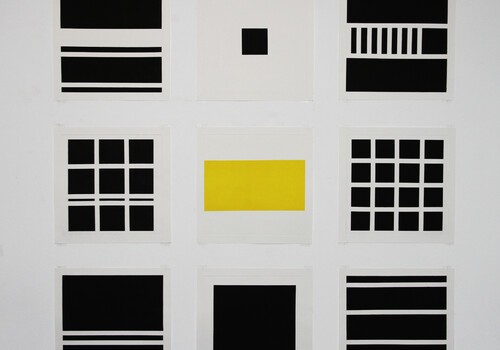

In the spirit of cohesion, I’m going to stretch this metaphor and say that Marcus Horswell’s work can be likened to the brain. Evidence: cerebral storage imagery. Three filing cabinets all face different directions. Two are Banal Office Beige and the other Asexual Eggshell Grey. They’re branded as “elite-built” and promise an “anti-tilt” mechanism. A sense of bureaucratic stability and assurance ensues. One could assume this would leave no room for leakage, but there’s evidence something has already been spilled. Six paintings in ROY G BIV are also on display. Some are lent against the filing cabinets and others are attached to giant pin boards. These works are made with acrylic paint using a silkscreen. Coffee and paprika are also listed in the materials, the traces of which could certainly be swabbed from any surface of a Melbourne sharehouse kitchen. The rainbow paintings allude to a filing system that corresponds with the cabinets, but what has been hidden or kept safe?

Fragments of intimacy are silk screened onto the dyed canvasses, images of subtle moments that arouse visceral memory. There are figures, a kiss, the sharing of a cigarette, indistinguishable limbs, hands covering a face. Circles interrupt, redacting certain aspects of the images. They’re kind of like the rims your coffee mug leaves on something it shouldn’t: bedsheets, important pieces of paper, a table that doesn’t belong to you. O’s like orifices or O’s like dots that make up the halftone printing process or O’s like the embrace as it is represented in xo. Or could they be multiplying cells or spy holes or binoculars or glory holes? They could be a hole as in a void, or a whole like a completeness.

To me, they represent an absence. Horswell’s installation recalls Melbourne artist Liam Osborne’s 2017 show Hot Copy at Punk Café in the presentation of monochrome screenprints. Osborne’s work Absolute Autonomy (2020) is also echoed in the use of office furniture and proppage. Filtered through intuition there persists an inexorable inheritance of a certain Melbourne sensibility.

Painting at VCA continues to provide a full body experience.

Gemma Topliss is a writer and artist from Naarm/Melbourne.