Fine Art, RMIT

By Grace Sandles

Creature comforts and comfort creatures. In a show two-thirds born of isolation in the home, symbols of childhood bedtimes have been perverted to striking effect. Portrayals of domestic spaces and fairy tale–nostalgia foreground interrogations of interiority in the art of RMIT’s fine arts graduates of 2022.

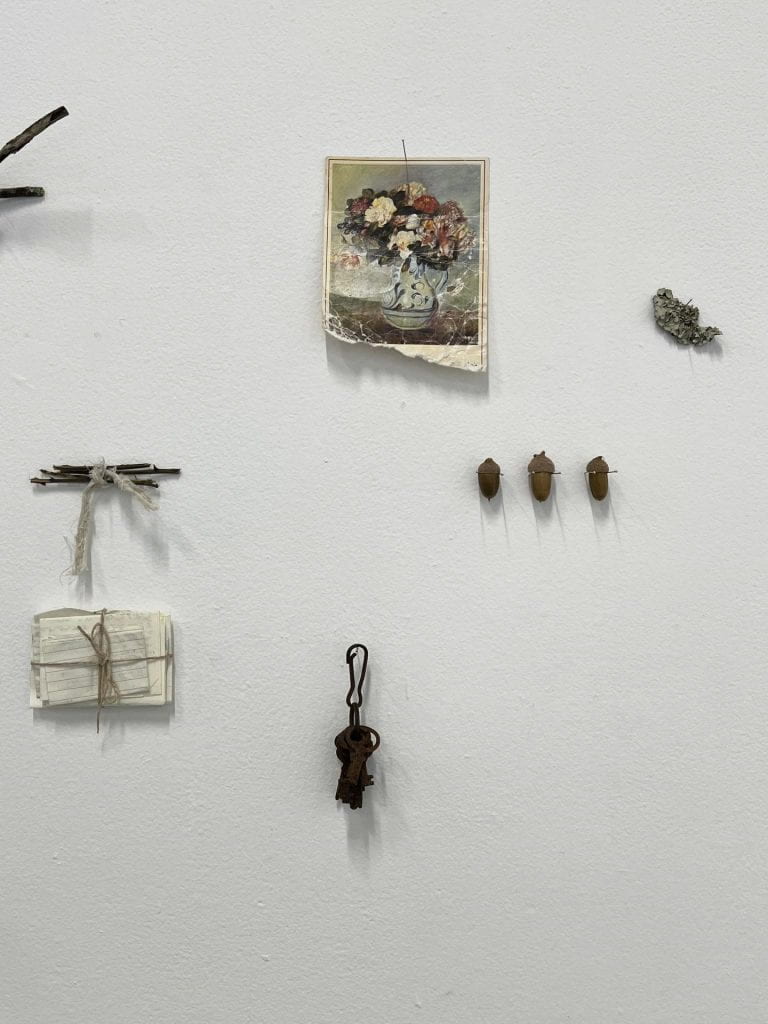

Drawing student Jasmine Duong’s installation The Heart that Bleeds is the Heart that Grows (2022) is an altar: a shrine to solitude and healing. The artwork comprises found objects (including lavender tied with ribbon, a vial of rose petals, pendants, a pentagram ring, a rusty key, and three journals) and tarot-inspired graphite on paper compositions. It culminates in the mise en scene of a young, curious, heartbroken teenager’s bedroom.

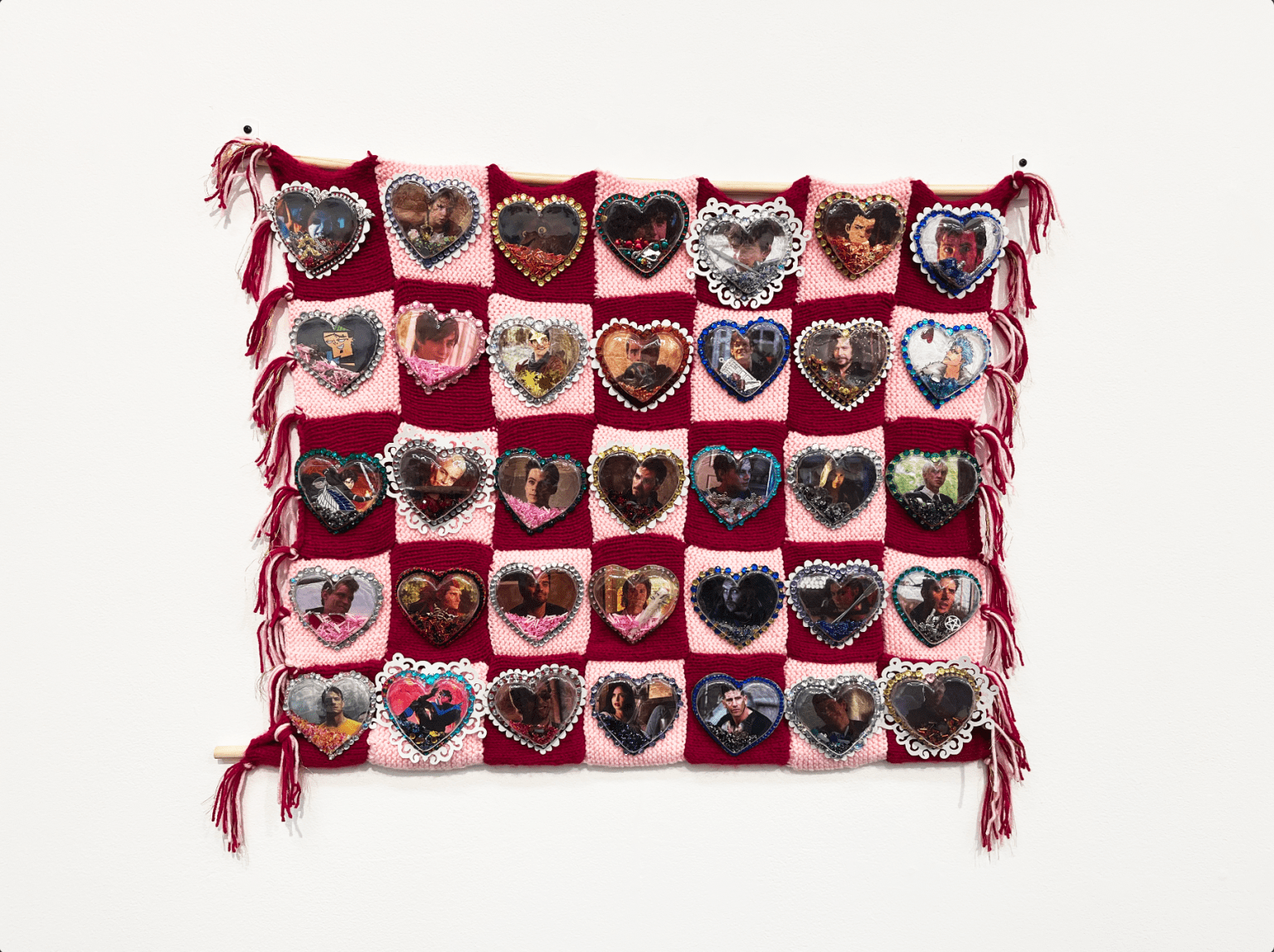

Should that teenager be an obsessive, fandom-belonging, diary-writing lover of pop culture, perhaps jewellery student Jale Sezai’s works might adorn their walls. I’ll never love anyone as much as I love you… or you… or you… or you… (an abridged version of a very long list detailing the many loves of my life) (2022) is a colourful, kitschy, and visually exciting mixed media blanket with 3D-printed plastic brooches. Here Sezai offers an exploration of the self through participation in community, and a celebration of girlhood and a girl’s eagerness to love. Each brooch frames a beloved character; there’s Merlin (eponymous), Peeta Mellark (Hunger Games), Huntress (DC comics), Daredevil (Marvel), Sirius (Harry Potter), Zuko (Avatar: The Last Airbender), and so on.

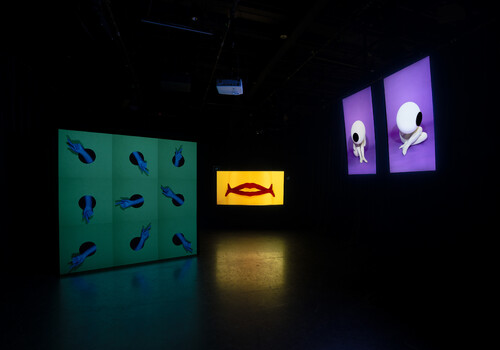

Across campus, sculpture student Jemma Prescott plays with scale to heighten the uncanniness of stuffed animals turned evil. Suspended from the ceiling, the painted calico fabric and clay menagerie of Comfort in the Fear (2022) advance a disquieting suggestion to the innocent attempt to catch one’s teddy animated à la Toy Story by pretending to be asleep.

Carly Spiteri technically belongs to the painting studio, but mixed media Gothic Nursery (2022), another installation, demonstrates a trend within the wider cohort of artists deconstructing mediums and experimenting with the gallery space. Spiteri recreates an infant child’s bedroom space but imbues every individual element with menace. Everything is black. There’s a painting on the back wall wishing “Sweet Nightmares.” If you look closely, you’ll notice dolls bisected as features of the shelving unit. Perched atop is a jumble of horse dolls warped to form a statement lamp. It’s a haunting, Addams-family-esque bedtime-story scene.

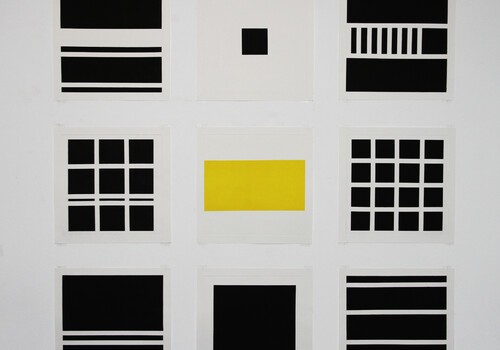

Equally gothic, Lloyd Collidge’s Madame Butterfly (2022) reinterprets the opera of the same name by late-Baroque composer Giacomo Puccini. The fairy-tale-style medievalism of the text is illustrated and animated in charcoal monochrome, another apt exploration of identity and selfhood making use of fairy-tale story elements. Once more, the hand of the artist is located in the act of distortion.

Jiayi Quek’s Big Bad Wolf: What Big Eyes you have (2022) is an ink drawing on book and mixed media installation. (Indeed, installation was a popular form for this cohort.) Quek pulls a fairy-tale right from within the pages of the “Bedtime Stories” volume in Gothic Nursery: Little Red Riding Hood. A looming shadow sits behind the hanging red hood- a clever trick of light placement and a sexual metaphor that reflects the dark symbolism of the original tale. Detailed and technically spectacular, the artist’s interpretation of the tale comments on the shameful perception of sex and its role in the perpetuation of sex crimes.

The bedroom, the stuffed-animal bedtime companion, and the bedtime story and its characters, appear pertinent for a cohort isolated in their bedrooms for much of their degrees. Rather than rejecting the domestic space and all its contents and continuations, the artists capitalised on their disaster-born intimacy with the worlds between those four walls, compellingly commenting on the formation of the self that happens there.

Grace Sandles is a writer and arts worker based in Naarm (Melbourne).