Honours, Victorian College of the Arts

By Emily Kostos

When I see cocktail frankfurts, Felicia’s iconic line from Pricilla Queen of the Desert irrevocably comes to mind: “how do you like your little boys, girls?” The association was provoked by VCA honour’s graduate Nyssa Levings’s constellation of sculptural works. The first of Levings’s works I encountered featured a crowd control fence and machine—not unlike a vintage food processor. A cocktail frankfurt attached to an appendage protruding from its left was spinning at high velocity and a decaying parsnip on its right—both moving at speeds that made their recognition as foodstuff challenging.

Jutting out from a nearby wall was a bent steel form cased in another red frankfurt skin. It had the feel of a DIY handle used to power a post-apocalyptic amusement park ride. As I wandered into the adjacent stable, another frankfurt-esque form poked its head surreptitiously through the wall. When I lifted my gaze, I was met with a dome surveillance mirror bolted to the wall, candidly capturing me in this humorous yet uneasy mise-en-scène. It is positioned within an institution repeatedly churning out franken-students and molding them into recognisable and acceptable stylistic prototypes. Levings’s phallic gestures may have been deployed as an anti-institutional metonym, tapping into consumption and productivity within the capitalist void. These works were titled collectively “YOU COULD BE A WINNER”, an apt choice given Leving received the Chin Chin award.

In the central exhibition walkway, a hills hoist, a cultural icon of 1950’s Australian suburbia, acted as a plinth to a bandaged prosthetic hand clasping an in-use hairdryer pointed at the ceiling. The air flow buoys a rebounding yellow balloon in the air, scrawled with the hand-written text of the works’ celebratory namesake. The low-frequency white noise of the hairdryer lulls one into the hypnotic complacency of disquieting nostalgia, one of by-gone dreams and empty promises. This lulling itself has been apprehended as something to consume, with YouTube promoting this sound as soothing for unsettled infants.

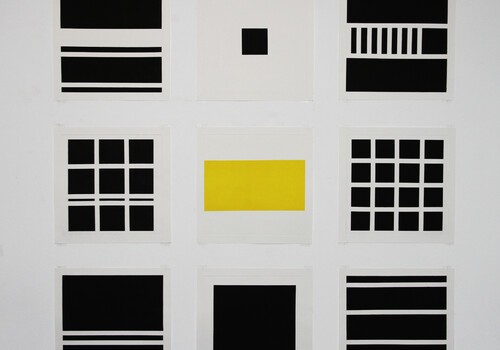

Nearby are a series of inkjet print transfers by honours graduate Angela Nolan that take us elsewhere—somewhere “dodgy”, as the text in Scriptures reads repeatedly across Nolan’s canvas. It is unclear if Nolan is alerting us to the dodginess of popular culture and image saturation (to which the majority of her source material refer) or the information loss in the ink transfer process itself, or both. Half of Nolan’s inkjet prints are transferred onto canvas and the other half onto sailcloth, a material inextricably tied to a history of white supremacy and invasion. This reference to colonialism can be traced in Insignia: a composite image with a red iron cross (a signifier of German military medals, bikie gangs and 90s surfboards) and an unknown femme fatale. Untitled 2 (PokerStars) and Untitled 1 (Chloe Sevigny GQ) hang as a discrete pair in the adjacent stable. Inverted respectively upside-down and horizontally, both images subvert, through process and orientation, the passive consumption of media and the objectification of women.

There are echoes of Nolan’s assemblage process in Charlie Robert’s inkjet prints, Buttercup, Pad Bay Dogs, Global Lunch 1 and Global Lunch 2. As composite images, their imagery is diluted as such that their forms and text require close inquiry to be, at least in part, discerned. At the very outset, walking into the stables designated for honour’s students, a clear interrogation of our relationship to image saturation, technology and capitalism emerged. From distorted machinery with questionable use value, to text and abstract shapes like Rorschach inkblot tests from a bygone civilization, these artists seem to ask: “how do you like to fill your little hedonistic void?”

Emily Kostos is currently practicing as an arts worker, artist and musician in Naarm (Melbourne). She has completed a Bachelor Art History/Diploma of Creative Arts at the University of Melbourne (2011) and a Masters of Art Therapy at La Trobe University (2013).