Fine Art, RMIT

By Sophie Lodge

Can a pink plastic hair dryer be a work of art? What about a tablecloth or a golf ball? Since Marcel Duchamp presented a men’s urinal as a work of art in 1917, the question of what constitutes “art” has pre-occupied the art world. The recent graduates of RMIT’s Bachelor of Fine Arts degree are no exception. For decades, RMIT’s heritage-overlayed walls have witnessed the creation of painting, drawing, sculpture and more. Though the school still imparts traditional skills, a myriad of interpretations emerges from the multi-disciplinary works showcased.

This barrier between traditional and non-traditional artmaking practices is importantly raised by Chloe Vella’s sculptural work Wunderkammern of Objectified Significance – Woman Claims that a Left Foot Boot is her Daughter and her Husband is a Dirty Couch (2022). Within the RMIT sculpture exhibition space, Vella’s artwork constructs two small, connected rooms that firstly position the viewer within a replica of a white cube gallery adorned in framed Picasso-esque self-portraits. When the second room is entered, however, the rigidity of the white cube gallery is abandoned. The viewer emerges into a chaotic arrangement of found and created objects that represent the complex nature of identity and self-expression. These found objects, things like plastic hairdryers, Jesus statues, and classic books are used as tools for self-portraiture. In the same manner that her framed Modernist drawings use oil pastels, Vella curates these objects as symbols of her own identity.

Vella’s sculpture is just one of a collection of graduate artworks that elevate mundane craft practices and everyday items. In the same way that English artist Greyson Perry incorporates ceramics and tapestry weaving into his art practice, RMIT graduate artists Chiara Zeta and Celeste Perry engage in a process of elevation of the art object that references traditionally “low art” practices of craft and textiles. Zeta’s artwork In/Visible: Femin-ine/ist Responses to Domestic Violence (2022) is comprised of white tablecloths and bedsheets that have been artfully embroidered with phrases such as “I can’t reduce my trauma to a fucking slogan”.

Within this work, Zeta’s employment of a domestic and traditionally feminine textile practice is starkly contrasted to her powerful use of language. The artist uses this dichotomy as a vehicle for expressing her own feminist rage. In a similar manner, Perry’s construction of plastic beaded necklace chains floating from a makeshift ceiling in Untitled installation (2022) references the craft activities of her childhood. The necklaces, whose arranged lettered beads spell sentences such as “child of divorce”, allude to the way that childhood nostalgia can obscure reality.

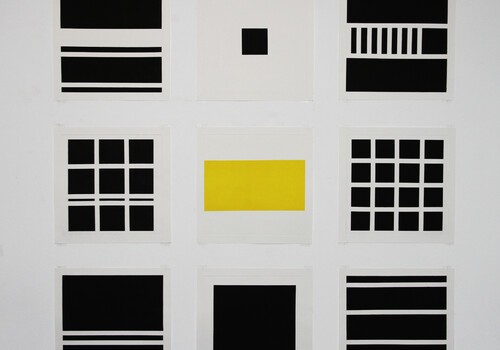

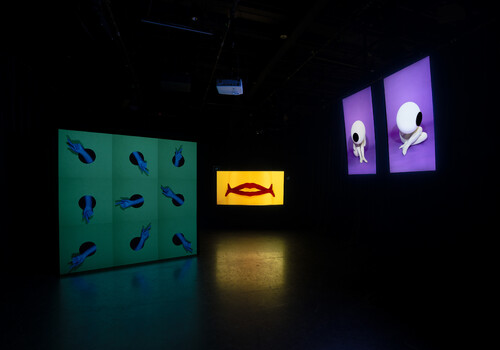

Through embracing these non-traditional approaches to art making, the artists of RMIT’s graduate class prove the depth of possibilities for art creation and presentation. Melissa Paul’s Enduring Self (2022), for example, is a video artwork that references digital behaviours in relation to self-representation. Presented on twelve RMIT computer monitors and supposedly using the monitors’ built-in cameras, Paul speaks to the democratising effects that widespread technologies have on art creation and exhibition. Ultimately, the artworks within RMIT’s graduate exhibition illustrate the infinite possibilities of what can be considered art, and how it can be created.

Sophie Lodge is a writer from Naarm (Melbourne) currently undertaking a Bachelor of Arts at the University of Melbourne.