Fine Art, RMIT

By Cam Wu

It’s a Wednesday, so I wish to stop existing in this corporeal form. It’s probably just my midweek misery talking, but sometimes being a body occupying space is so exhaustingly complicated. Four artists at the RMIT graduate exhibition seem just as cognizant of this complexity, interrogating the physical and psychosocial spaces we inhabit.

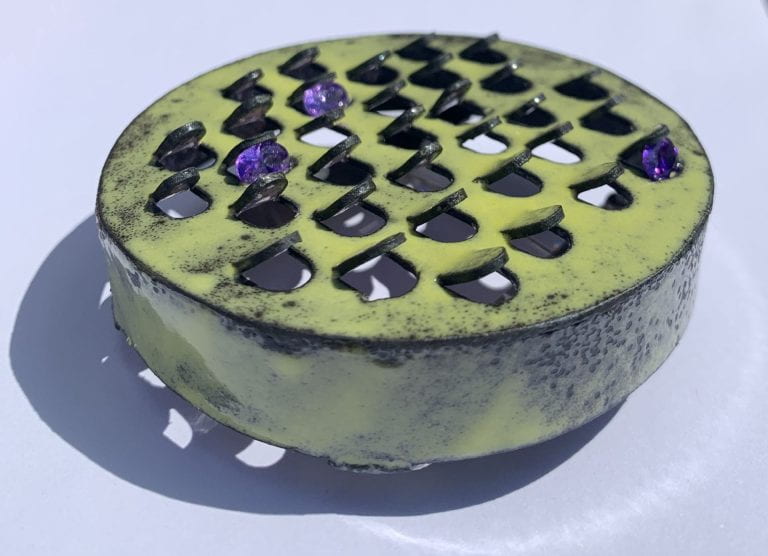

Forged from welded steel and enamel, Beth Sanderson’s wearable objects evoke the humble kitchen grater. The artist issues a conspicuous callout to the at-times suffocating labour of food preparation, but Sanderson’s wearable graters are undeniably beautiful in their precision and ornamental settings. And not for the sake of palliating domestic toil. They remind us that there is joy in the quotidian, beauty in the ordinary.

As I look over the grater-brooches before me, I have to smile at the absurd thought of shredding carrots using a shiny blue pearl-encrusted grater. From now on, the repetitive grind of preparing weeknight dinners need not be so uninspiringly dull.

Mia Harrison’s video installation Finally, I Wish to be at Peace, offers a different take on the entrapment of domesticity. In an enclosed room, Harrison presents a water-filled glass tank. Inside is a dioramic model of a bedroom and ensuite, its miniature floorboards already peeling away from the base, signalling their rapid decay in the aquatic encasement.

I’m struck with a low-level panic as I watch the video projected on the back wall. The artist is submerged underwater, her face filling the digital frame. Her dead fish gaze stares right through the camera, long red hair floating placidly around her head like some sort of morbid Ariel. How long can she stay under for? She’s completely sealed away by the confines of the video screen. Strangely, as Harrison’s expression slackens, she seems at peace. I find myself more helpless than she.

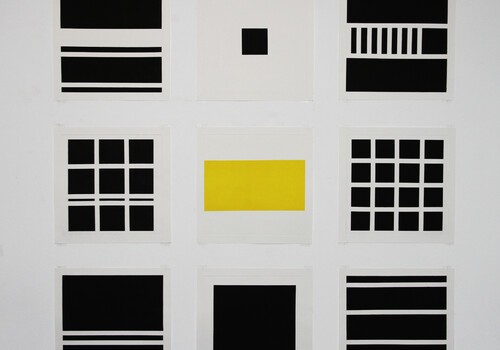

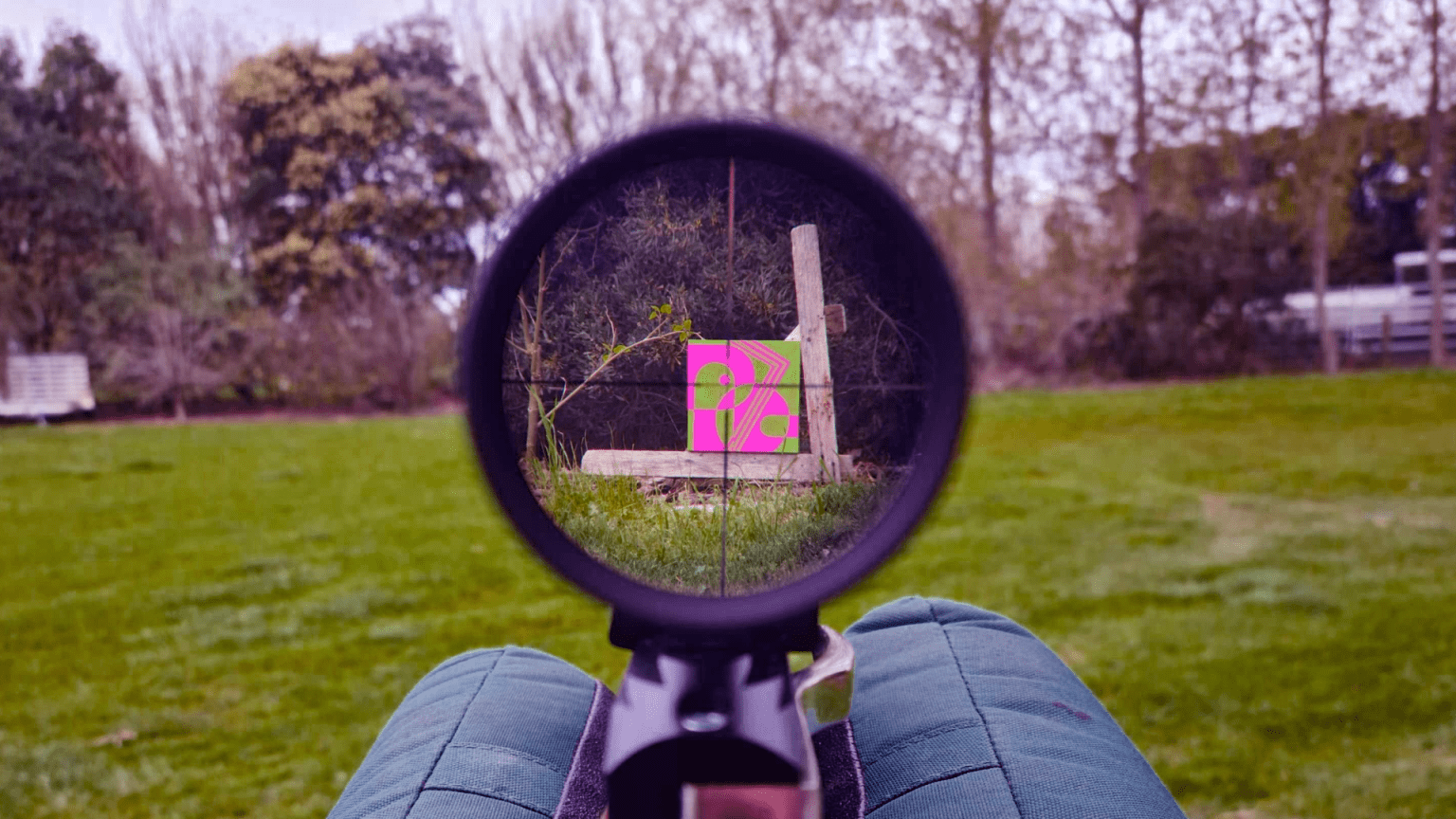

Conversely, Beth Kay opens up a window between the art object and the space around it. The artist-cum-markswoman’s abstract paintings are united by pink and green curvilinear shapes and precise angles. Most strikingly, each composition is punctured by three gunshots.

It’s hard to forget what the gun represents in our culture–in any culture. To puncture a hole in something is to create a rupture. Here, Kay’s rifle has marked out entryways; each ballistic perforation is a peephole into another dimension. One work is suspended in front of a window, and through the three bullet holes, I can see out into the city. It’s peaceful. The irony is not lost on me.

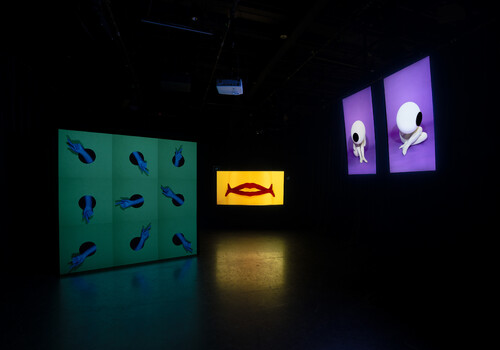

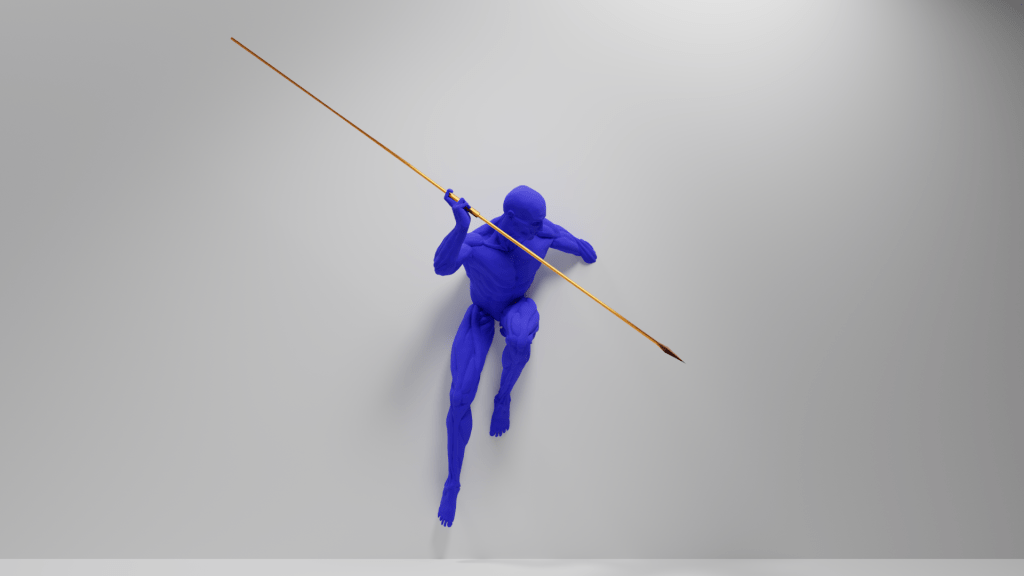

Across the road, another extradimensional intervention is taking place. In the far back corner of the Sculpture gallery, there’s a bald man on the wall. And his skin is blue. Jazz B Duncan’s life-sized, 3D-printed sculpture JAVELIN is materialising out of the wall, a metallic javelin gripped in his right hand.

The weapon’s pointed tip is aimed towards a white wall of the gallery. Maybe this is some kind of institutional critique, death to the white cube by blue man. No, it appears that the figure’s caught in an intergalactic tussle, having spawned in RMIT Building 37. Where Kay holds quite power, constructing an inviting entrance into the space around the work, Duncan’s sculpture wields brute force, carving out a fissure in the gallery. Punctuating this work is an acute awareness of the space that holds us, and its transformative potential. Anything could happen here, the cobalt man reminds me. That alone is powerful enough to fight even the most severe case of the weekday blues.

Cam Wu is an artist living and working on Wurundjeri and Boon Wurrung land. She is currently completing a Bachelor of Fine Art/Bachelor of Arts at Monash University.