Honours, Victorian College of the Arts

By Eliza Baker

Was the past as wonderful as we remember? Or are our memories shaped by our relation to the present? Do we make yesterday seem brighter and today gloomier? At the VCA honours exhibition, where cool ambiguous sculptures confronted me at every turn, I found myself drawn to art alluding to a quieter, simpler time. It is only natural that during a pandemic we find ourselves yearning for the beforetime, or to escape into an alternate world where “now” didn’t happen. And yet, our affinity for old media and retro aesthetics has always been strong. They allow us to pluck out our warmest memories, shelter from the fast-paced world for a while, and find something to complain about, to long for, in the present. But is this justified? Following this line of enquiry, I wrapped myself in the arms of the familiar, indulging in the nostalgic and memory-based works of a few ambitious artists.

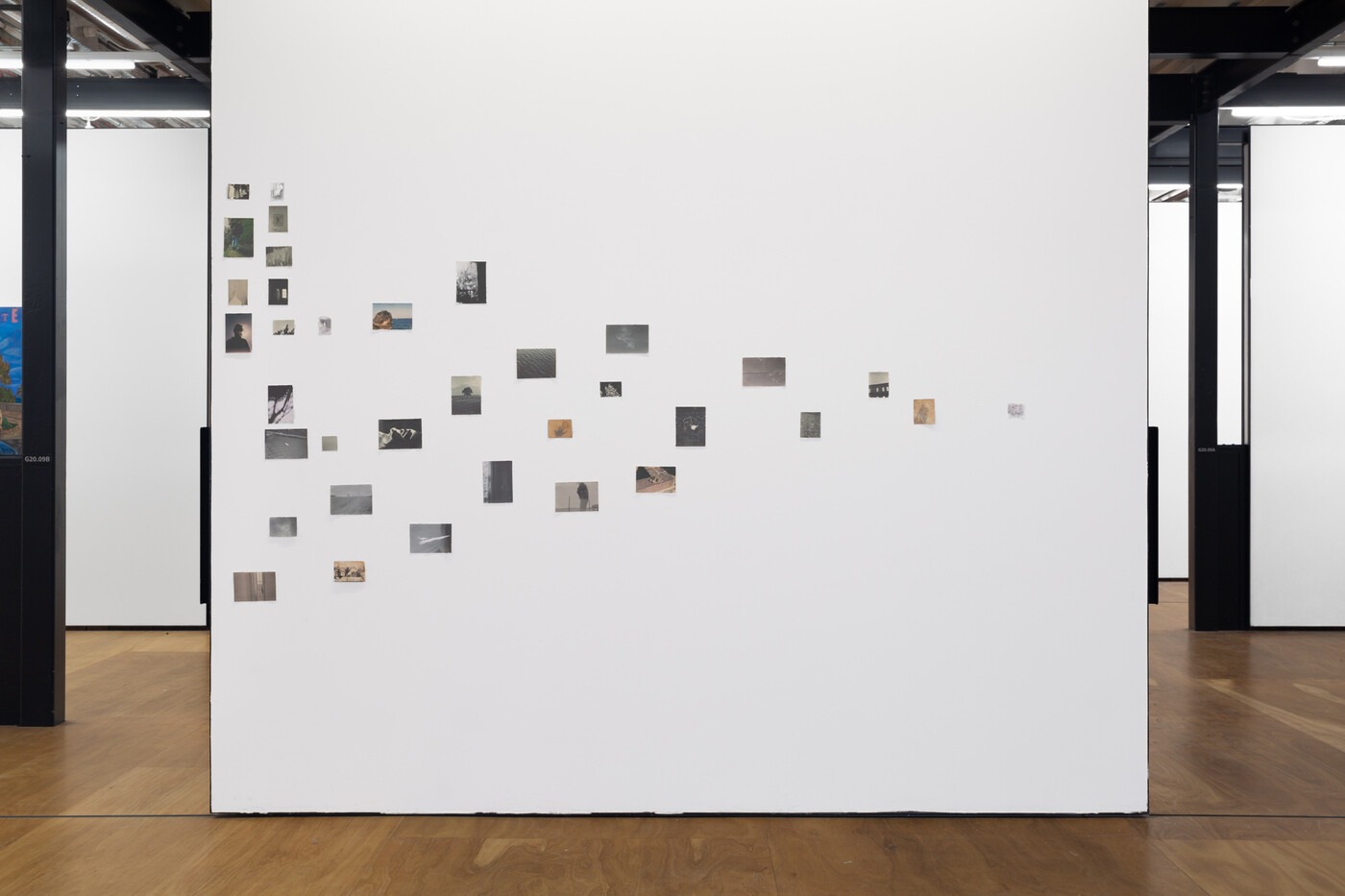

Grace Spence’s work Constellation unfolds laterally across the compartmented gallery spaces of The Stables. Through a wunderkammer of grainy photographs, thumbnail sketches, and sentimental objects, Spence transported me into a dreamy summer-land; one that was hers but that simultaneously taps into a collective ideal of youthful joy. The small images oblige you to draw close, entering their tiny sensory landscapes. Floating over them I heard the crashing of water on the beach, smelled gum leaves and country air, felt the warm bed linen of a Sunday morning. Across from these photos, assorted memorabilia are aligned on wooden shelves. A yellow, crumpled sticky note reading “Grace: I am at meeting, will be back around 12:20”, stood out to me. How perfectly it demonstrates our attachment to everyday objects. Why we keep them, we sometimes do not know, but they spark something within us that would else lie forgotten.

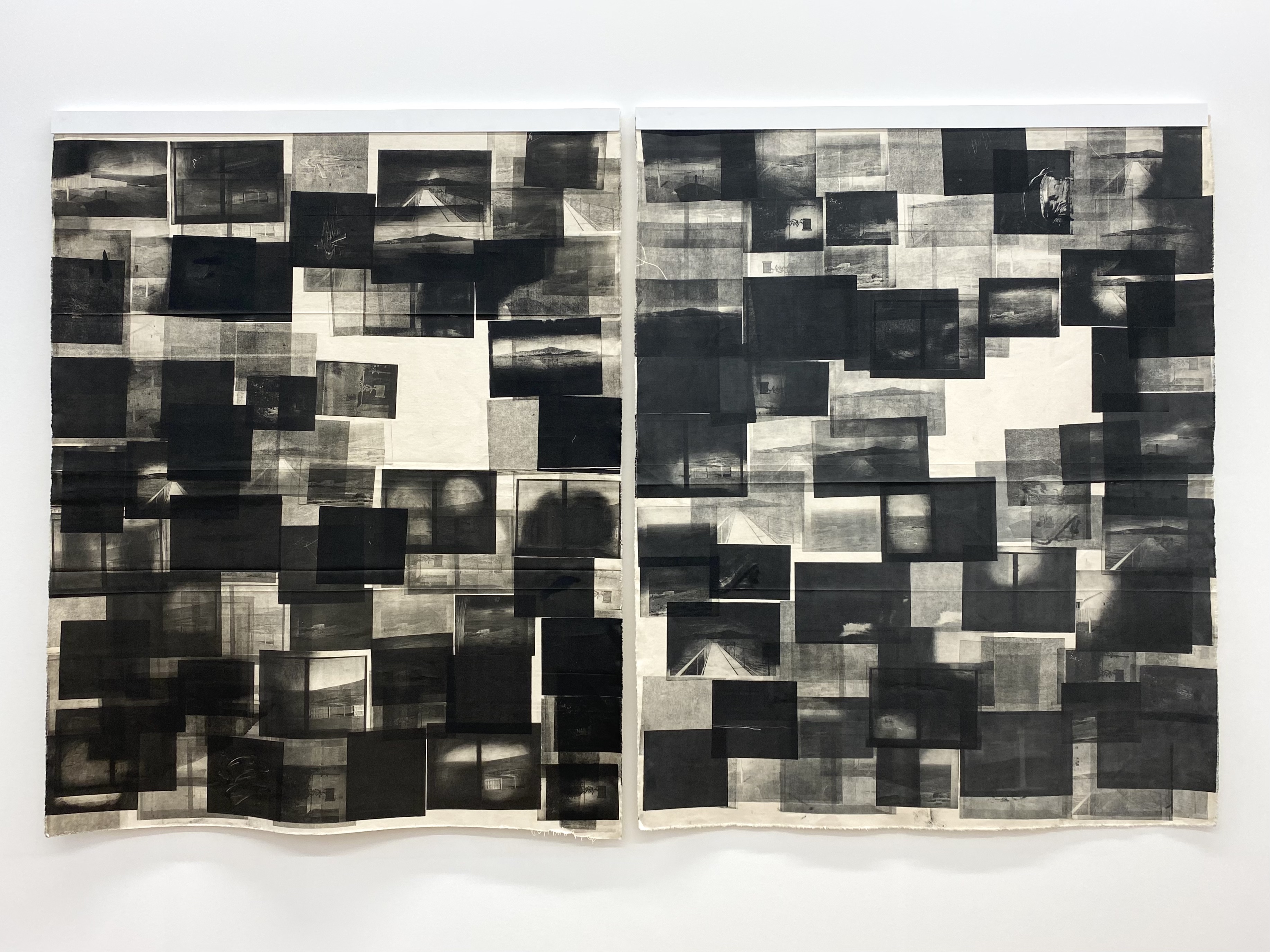

Meg F Evans is another artist whose work whisked me away from the present, this time into a series of gothic landscapes featured in A walk mimesis 1&2. Printed on two lengths of suspended canvas that dances in the breeze, Evans layers black-and-white photos taken on walks. In them, I imagined myself as a modern-day Catherine Earnshaw from Wuthering Heights, brooding over some terrible misfortune. Some versions are bleached, others almost black, others are obscured by textured markings that give them an aged, spectral quality. As with Spence’s work, I was called away to some quiet, wondrous place of imperfect memory, and was quite happy to shelter there.

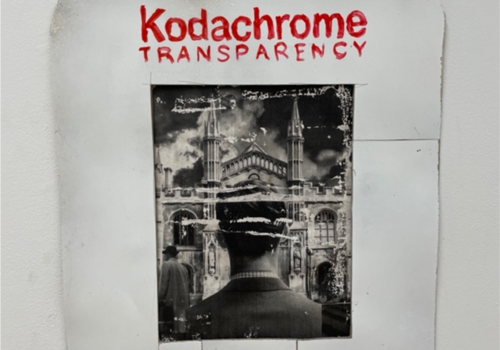

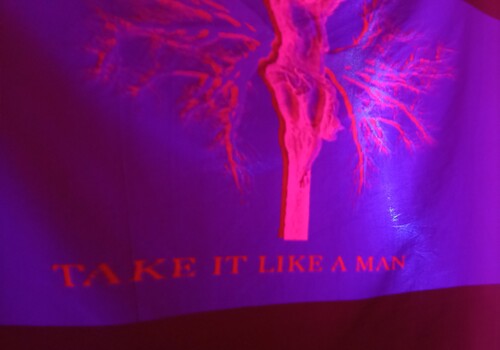

Nostalgia also has a strong presence in Camille Perry’s art, and her focus on technology and artifice cleverly shaped her interpretation of the theme. In Kodak Hill and Where the Merri meets Edgars Creek, crackly montages of landscapes and city scenes flash by on old, boxy tv sets, like the home videos your grandparents make you watch when you’re home for the holidays. The landscapes, however, are marred by the same crackles and spots that make them appear so romantic—Perry’s comment on the toxic processes of traditionally developed photographs. Regardless, I found myself yearning for the drowsy summers of times past, peppered with similar shots. How easily we can be led from the present. To Make Amends #1 & 2# certainly lured me away, only to yank me out again. Perry’s two, slightly crumpled landscape photographs give the impression of an Australia from centuries ago, thick with bush. Preoccupied as I was with their dreamy, sepia fade, which inspired imaginings of an undisturbed landscape, it took me an embarrassingly long time to recognise the rubbish choking the rivers in each of the photographs, betraying their recency. The works revealed my love of “old stuff” for what it is—an escape into times I did not really experience and can therefore idealise in my head. Perry reminded me that we’re not in the olden days, there is rubbish clogging the rivers, and the times we look back on are not as spotless as we make them out to be. Regardless, I can’t help but continue to be drawn to the aesthetic indulgences of the vintage, the obsolete—that romantic past that never was—a past that mesmerises artists and aesthetes alike.

Eliza is a writer working in Naarm/Melbourne. She recently completed a Bachelor of Arts in Art History at the University of Melbourne.