Bachelor of Art (Fine Art) (Honours), RMIT

By Bianca Arthur-Hull

Do the labyrinthine corridors of RMIT inspire a search for lost gods? Or perhaps it is our precarious times (once again) that are to blame for the crisis of devotion on show at the RMIT Honours graduate exhibition at the city campus in late November. Explorations of religious reckoning will always be intensely personal. But in art they are not without precedent, and several works in this show explored spirituality by using—or subverting—the kind of pre-modern religious iconography that has a long tradition in art and devotion. References to gods, icons, religion and relics are wonderfully classic. Or perhaps they are a tired pretence. It’s hard to tell with holy mysteries, least of all when the only truism for the post-pandemic devotee is that iconoclasm reigns supreme. It’s iconoclasm of the sexy, blasphemous and perverse type, where you’re welcome to keep your shiny relics, but be sure to make them shocking.

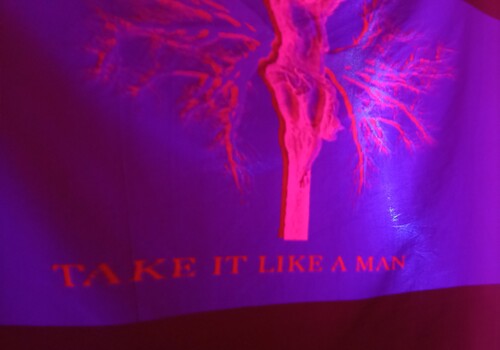

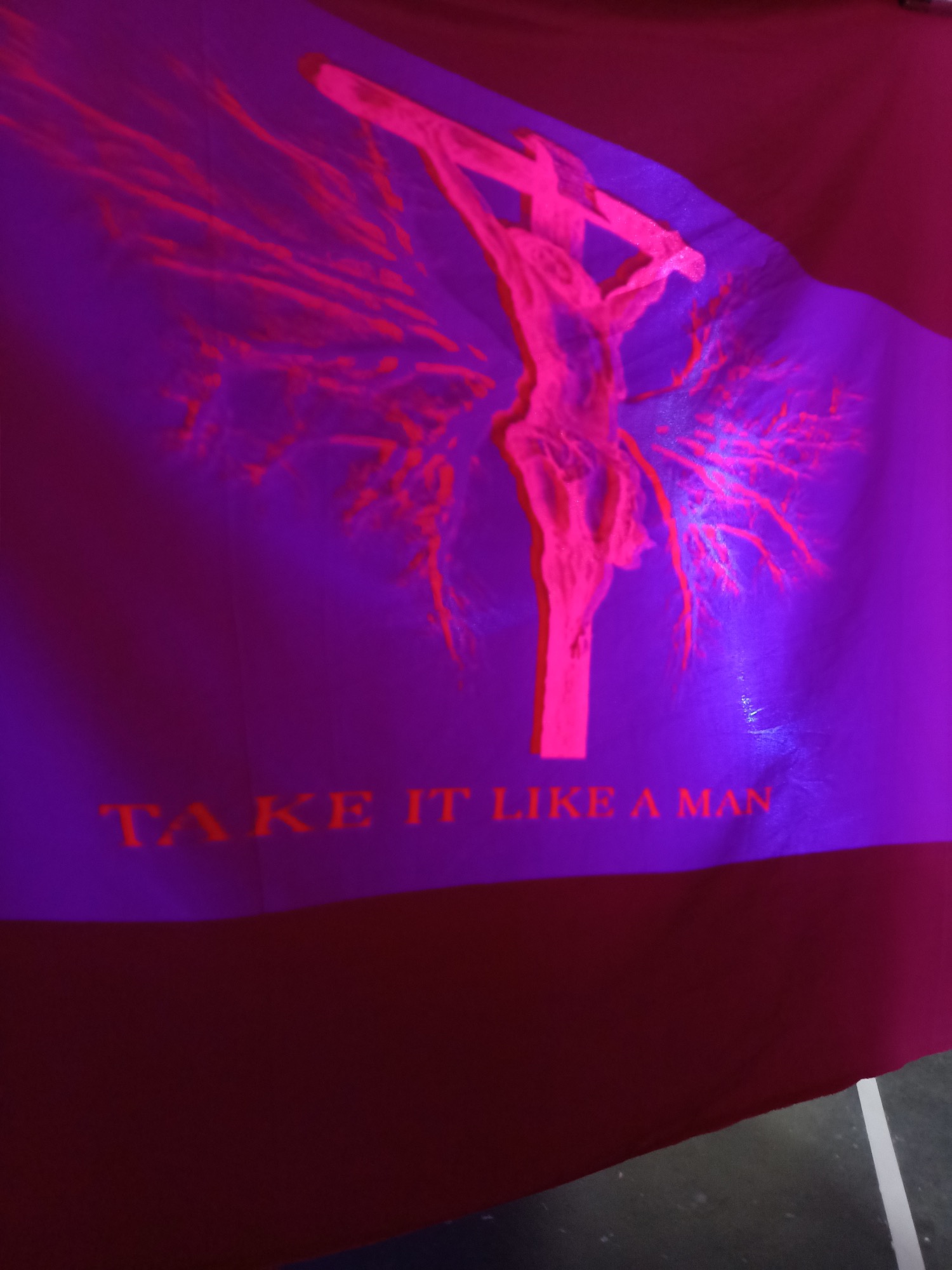

On a top floor, pulling back a pink satin curtain, I encounter Sam Kariotis’ Sideways Sacrament, one of the more clearly iconoclastic installations. The curtain is projected with an Andreas Serrano-esque crucified Christ, and behind it is a shrine of found objects, both pagan and Catholic, banal and valuable: rosaries, tarot cards, condoms, testosterone. The installation is raunchy Baroque excess for the 21st century: a ritual in pink taffeta. Candles illuminate the space and the diffused light is serene. But it’s also cramped and awkward to navigate, one of the pitfalls of RMIT’s erratic studio-cum-exhibition spaces. I almost step on The Hermit tarot card (unknown journey?) then a hip flask (happy resolution!)

The intimacy of this place is sacred. But I also feel that these sexually-and-devotionally-charged objects laid out on piles of pink amount to little if not by association and conflict, as if their esoteric and/or sexual cachet (and the irony therein) is doing most of the work. It’s just me, but I leave wanting more than allusions to erstwhile grandeur.

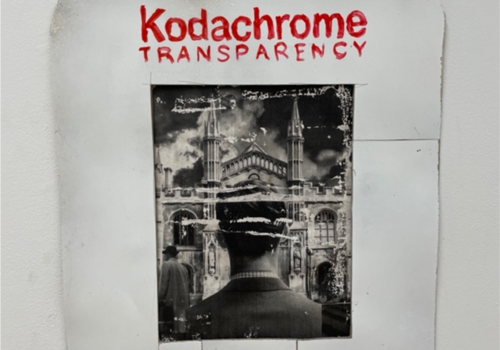

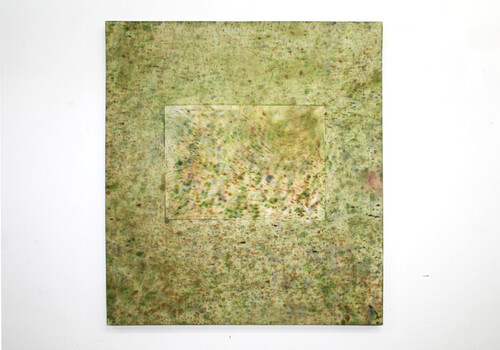

Downstairs, Johanna van der Linden approaches religious symbolism in a way that differs from Kariotis. Her work Growing up my mother swept the floors of our Church, then our kitchen: Imprint, absence and the un-sacred object feels like a post-Minimalist church turned sour in the face of family histories. The work is a response to the female body, power and Christianity, and I welcome her pared-down confidence. Her transparent Shroud, made of a repurposed curtain, latex and other mixed media, is placed by a stained-glass window. Its filmy beige is intercepted with pink veins reminiscent—ghoulishly—of flayed skin. Both blood and beauty have been drained here. I look at her altarpiece Heirophanies and struggle to see what ever could have been beautiful, really, about a three-panelled painting. Here, only these shells remain.

I descend further into the bowels of the building and discover Shan Dante and their debauched pantheistic cabaret performance piece Temperamental Crossroads. Dante—infernal namesake apt—stands back to me on a plinth, flicking their metal talons as if sharpening a knife for slaughter. They turn, telling me “I am a puppet ruled by the agency of god-like creatures”. Later, they strip off to become a campy and unnerving Go-Go dancer reminiscent of Félix González-Torres’ 1991 work “Untitled” (Go-Go Dancing Platform)—complete with gold hotpants. After traipsing up and down staircases, Dante’s piece feels like the self-assured conclusion to a show of ritualistic crises. They continue to preach, and I am converted.

I need no evangelist to convince me of the appeal of religious iconography. Even the smallest reference is enough to envelope the work within a tradition with luxurious mystique. Too often, though, the reference does a lot of the heavy lifting. Subversion thus becomes the only route to finding personal stories in religious imagery: something sacred becomes something perverse. It amounts to a kind of modern iconography for the devotionally-intrigued. No longer do we subscribe to gilt martyrs or sincerity, but to their disillusion and decay. Corrupt those saints! And while you’re there make sure they’re sexy, stylish and oh so depraved.

Bianca Arthur-Hull is an arts writer and researcher living in Naarm/Melbourne. Her recent research examined preconceptions of early modern art and its reception in Australia.