Bachelor of Fine Art, MADA

By Erin Hallyburton

To grieve in the presence of others is an expression of love. As we come to the end of our second year in a global pandemic, the work of graduates Nic Trifiletti, Lottie van Wijck and Carmel Ben-David shows us ways to connect with others while navigating grief. In the context of Melbourne, where multiple long periods of lockdown compounded the effects of sorrow and loss, these artists have reflected on other experiences of trauma and sought out ways to heal.

Nic Trifiletti’s installation A hairs breadth (2021) consists of a grid-like formation containing nine concrete slabs hovering just above the floor, appearing weightless and fragile. Their fragility is confirmed by a fractured slab that rests upon a stack of printed white paper in the back row. Amongst the concrete works are three reams of paper carrying short sections of text, and there is a poem mounted on the wall behind the slabs.

Playing on an adjacent wall is a video depicting Trifiletti’s grandfather walking around a tall fennel plant in bloom. The written text is key, as it connects the migration of sea birds to the experiences of the artist’s grandfather of migrating from Sicily to Australia, where he worked as a concreter. Trifiletti employs writing as a medium for exploring the messiness of relating to his ancestry. One text explains that, “In Italian, the word for fennel, finocchio, is a derogatory term for a gay man”. Prejudice born of a particular time and place can be passed down and disseminated through familial lineage. The four texts navigate inheritance and grief, prejudice and loss, displacement and creating a place for yourself. We witness the artist questioning what should be held on to and what must be left behind in the process of finding peace.

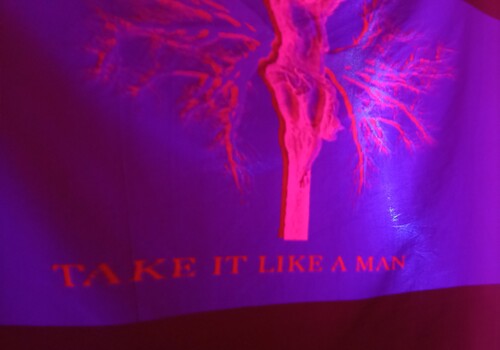

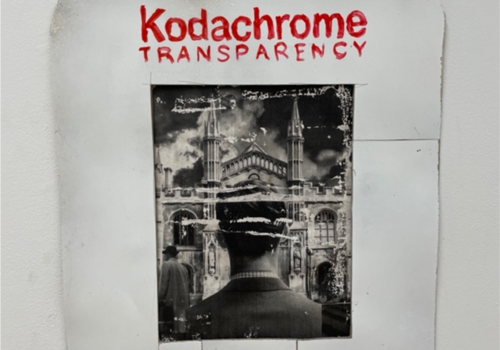

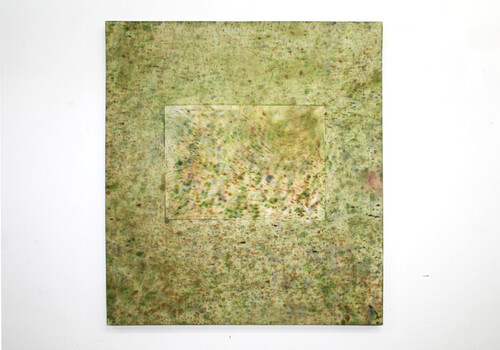

Like Trifiletti, Carmel Ben-David’s installation Inverted Image of a Cherry Tree (2021) draws on her grandfather’s ancestry. His experience as a Holocaust survivor and the effects of intergenerational trauma are examined through text and image. Ben-David’s text is written as though it was relayed to the artist by a parent. The story describes her grandfather’s upbringing as a young Jewish boy in Poland, his experiences during the war and immigration to Palestine. A cherry tree is a recurring motif in the text and photographic works, symbolising happy memories of life before the war. In the photographs, the tree is blurred, or distorted by lenses and liquids. Pocket-sized photographic prints, optical lenses and enamel-coated copper plates line the walls of the space, inviting us to look closely, but without ever being able to discern each image in their entirety: the cherry tree is always just outside of our grasp. Perhaps this suggests that we cannot escape trauma by chasing after the spectre of what came before. We can’t go back, but we can speak to each other about our loss. There is catharsis in sharing our grief with others. We let go to grieve and grieve to let go.

Grief and loss are also palpable in Lottie van Wijck’s installation Tracing Tarrawarra (2021), composed of three large, scorched fence posts propped against the white walls of the gallery. The posts were taken from the artist’s back garden, where they were charred in the 2009 Black Saturday bushfires. The fence posts are material manifestations of the trauma inflicted on the land and the community where the artist lived. Here, the repurposed posts are reimagined as sculptural forms resting dormant and cobwebbed. But sweeping charcoal marks on the walls from the posts and powdery residue on the floor imply movement. These drawing gestures embed traces of the fire’s scorched wood into the space. These marks narrate an outburst of energy, where the dormant vestiges of loss encapsulated in the posts are expressed through movement. Grief is expressed and witnessed by others in a process of healing.

Erin Hallyburton is an artist and writer who lives and works in Naarm (Melbourne). Her sculptural practice engages with fat studies and intersectional theory to examine the conceptual and material limits of the body, and how these limits manifest in certain sites. Hallyburton is a Bachelor of Fine Arts (Honours) graduate at Monash University.