Bachelor of Art (Fine Art) (Honours), RMIT

By Uswa Qureshi

Like most words, “home” connotes a multiplicity of meanings. Unlike most words, these meanings are intensely personal, individual, sometimes conflicting, and as such can be hard to state or grasp. Some of the strongest works in the 2021 RMIT Honours cohort gave expression to the idea of home in wondrous ways, all while evading the pretension and esotericism that can plague a group of emerging artists with something to prove.

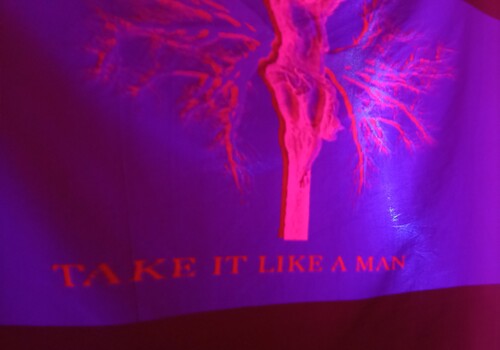

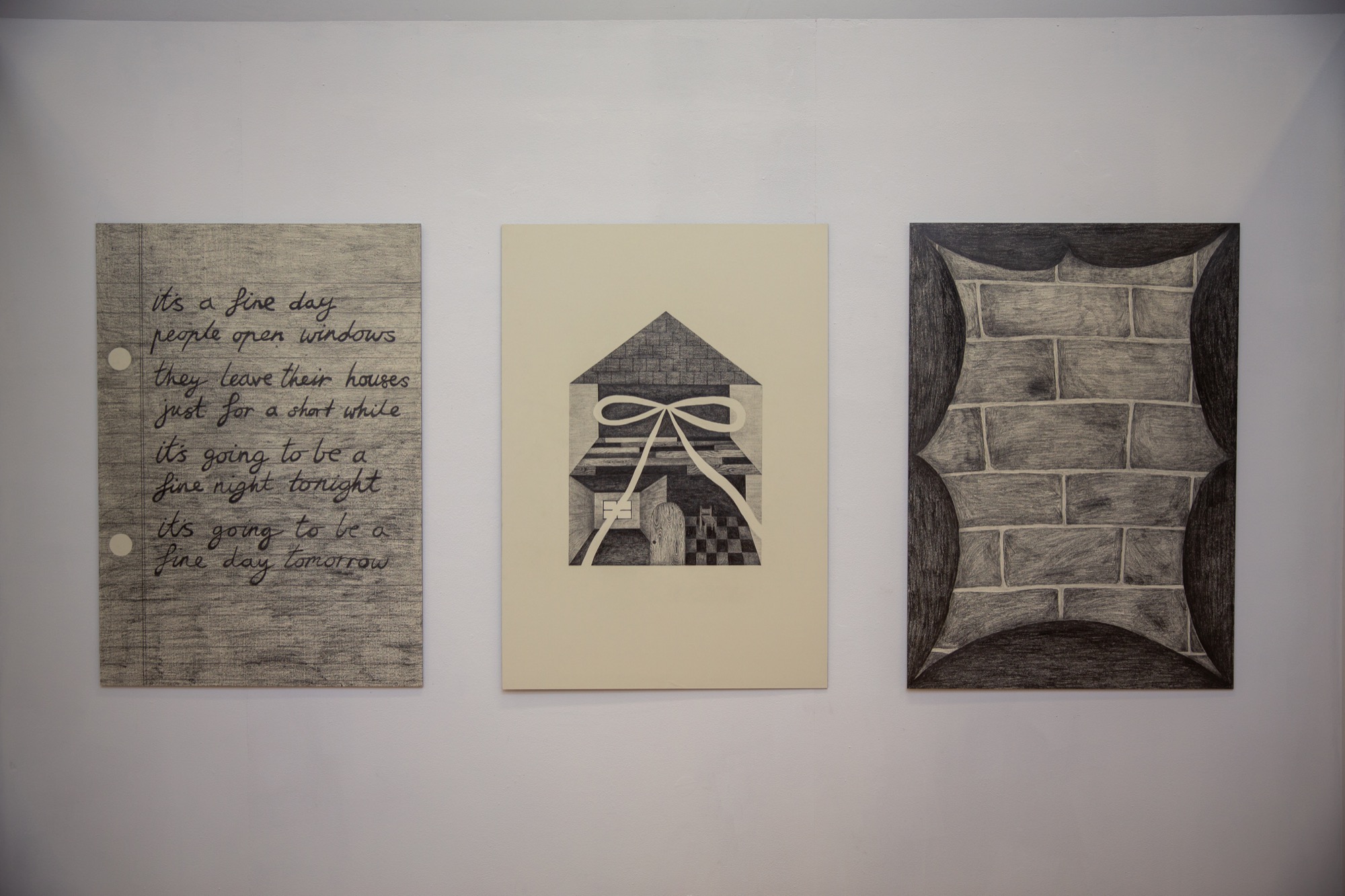

Over the past two years, most of us have sat with the idea of “home” perhaps more than we would’ve liked. Rumer Guario’s series of five drawings and a sculptural piece, entitled Poke Me Where It Hurts (2021), is a reflection on mark making, mysticism and the domestic. Though the work may not explicitly reference lockdown, it achieved a near impossible feat—it flipped my perspective on a genre of topical artmaking that I believed was no longer capable of being compelling. One drawing recalls the optimistic intermediary stage of exiting lockdown with an octet from Opus III’s 1992 song It’s A Fine Day.

The home is not represented as a place of loneliness or pain, as we are accustomed to viewing it recently, but instead as a source of solace and magic, a gift wrapped up in a negative space bow. Sparks, drawn curtains and meticulously rendered wood and brick textures hint at an alchemical elevation of the mundane. The bow motif is repeated on a life size fence grounded with pink stars. The sculpture is a delightfully cartoonish extension of the drawings’ thematic concerns but is awkwardly positioned in the centre of a walkway, spatially detached from the drawings, which seem at home against the walls. Nonetheless, Guario’s sweet drawings, made fuzzy with visible pencil strokes and the tooth of laid paper underneath, are a celebration of the quiet, magical joys that live with us in our homes.

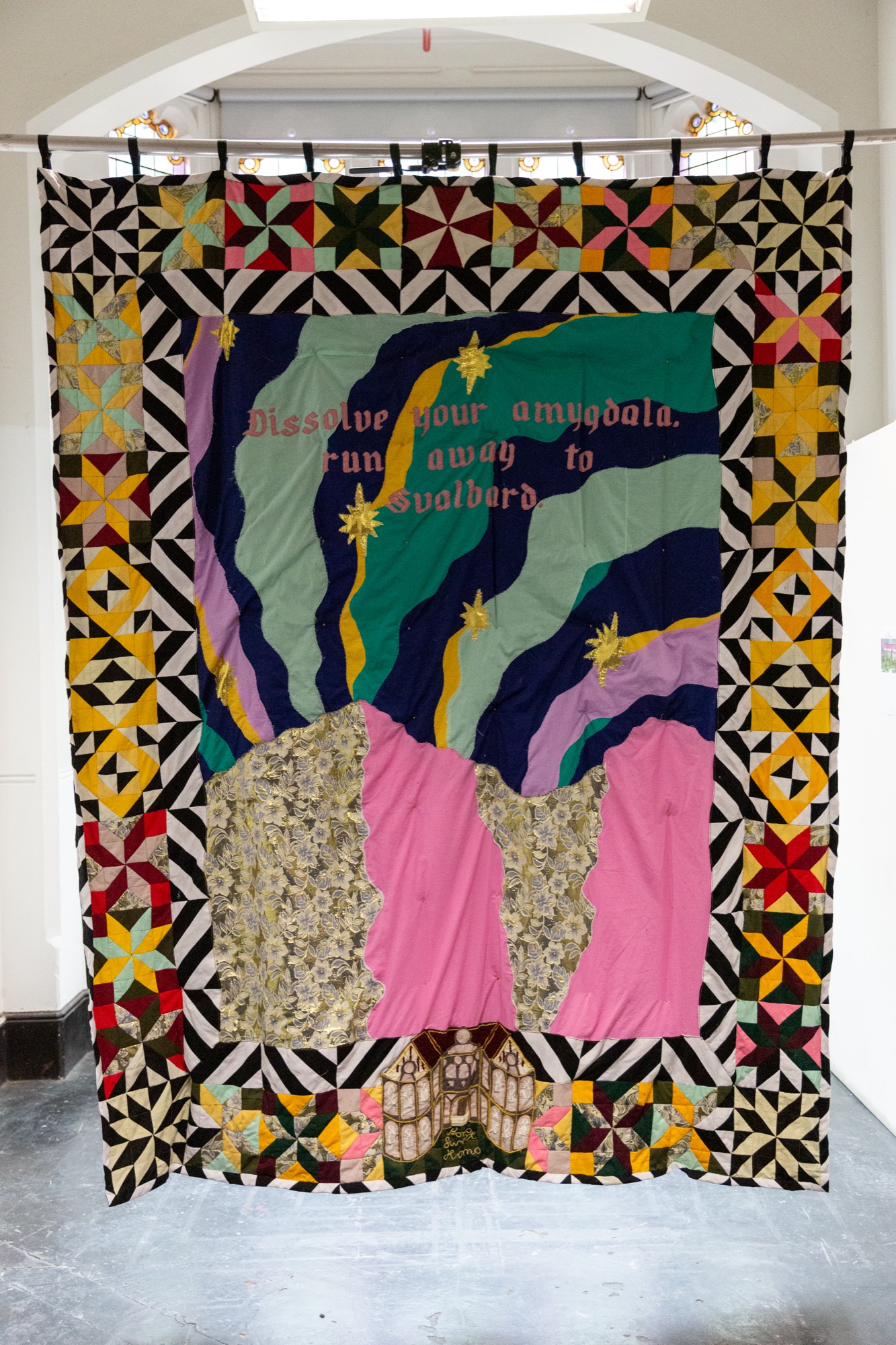

A sense of magic also seems to pervade Anselma Forlano’s work, Queer Shame as Method and Material (2021). A hanging quilt acts as a curtain sheltering the installation site’s stained-glass alcove. The centre panel of the quilt features a multicolour landscape gilt with stars and the words, “Dissolve your amygdala. run away to Svalbard” (a remote Norwegian archipelago). Beneath this centre panel is an ornate stitched scene of a house labelled “Homo Sweet Homo”. The quilt was designed and made collaboratively with the artist’s friend Jorja Timms, and it is easy to see the loving bond that infuses the fabric, the “sweet homo” a representation of the chosen family that is so intrinsic to the queer experience.

Behind the quilt is a plinth, the top of which is embedded with two silver knives, one of them a mezzaluna cheekily—or perhaps bitterly—declaring “WIFE MATERIAL” in an engraving above the blade. The movements of chopping are physicalised with marks, nicks and remnants of parsley juice on the surface of the plinth. The incorporation of text into the mezzaluna and the quilt is imbued with a sense of humour and fantasy. Both objects invoke seemingly antithetical queer longings: on one hand for domesticity and on the other for escape to a fantastical alternate reality—for becoming a Northern Light in the frigid reaches of Svalbard. Though queer shame may motivate the work, its outcome is an expression of the dazzling, mountainous desires that decorate a queer mind.

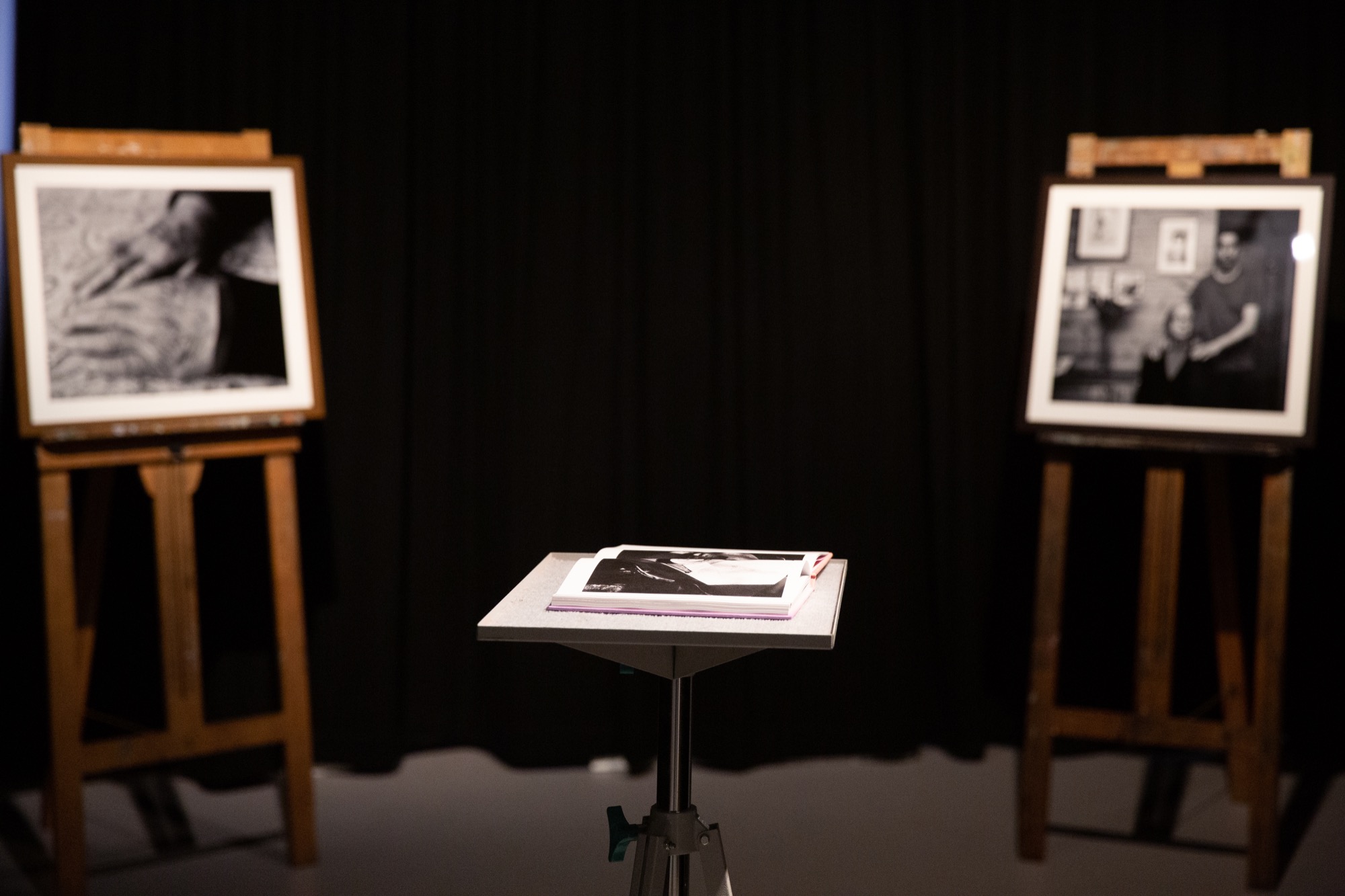

In contrast with the grandeur and spectacle of Forlano’s work, Panayiotis Kasseris’s photography, entitled I Am Looking for a Homeland (2021), focuses on the minutiae of his relationship with his mother. Three of the black and white prints zoom in on his mother’s wrinkled hands, and in one they clasp his own. Viewing such intimate vignettes of Kasseris and his mother could feel like watching a family of strangers through a window. The installation of the prints helps to avoids this. They are framed and placed on easels surrounding a table on which a book sits, a display that invites the viewer to step inside the circular arrangement. Looking at the photographs, I felt honoured to be let into this maternal relationship. Turning the pages of the book felt like flipping through a private photo album, an immigrant’s bridge between multiple lives.

One might assume that extended confinement might create conditions where artists are stifled, bereft of experiences worth translating into art. Instead, the RMIT Honours artists demonstrated the font of inspiration that home and the relationships within can be.

Uswa Qureshi is a writer and artist living in Naarm (Melbourne). They recently completed their Bachelor of Arts in Art History and Linguistics at the University of Melbourne.