Master of Contemporary Art, Victorian College of the Arts

By Sirui Yang

Whispers in the audio are like mist, floating and spreading out along the spiral track on the floor. They are emanating from 12 questions for snail-man / 12 questions for snails (2023), an audio track that shares a conversation between a snail and a human.

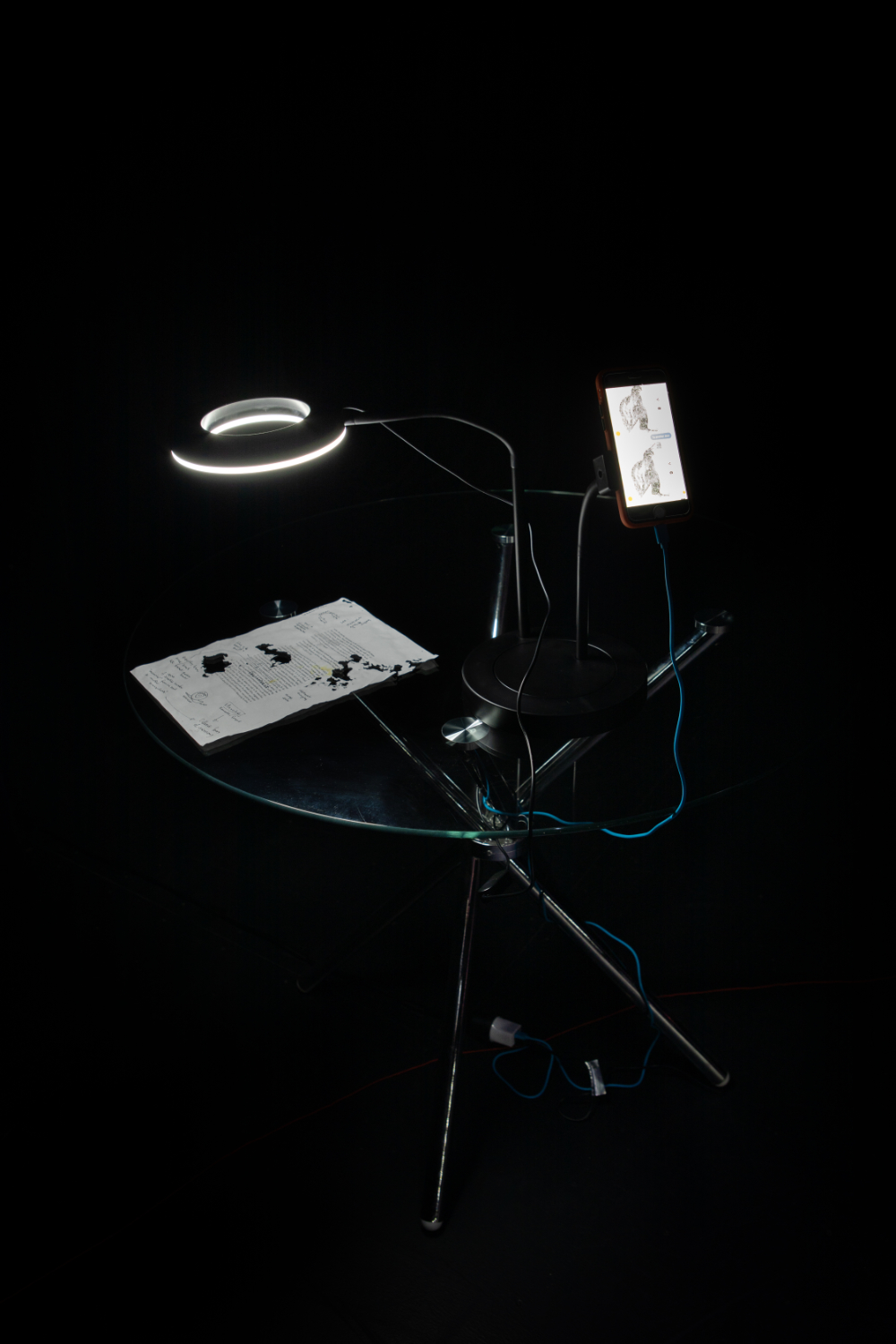

We are in a tranquil space created by the artist James Nunn, illuminated by a single beam of light at its centre. At the heart of Nunn’s installation This will be our amphalos, high on a pedestal, centre-stage, a translucent plastic lettuce container, placed upside-down, is like a sort of altar for a humble god.

Inspired by a niche obsession with snail racing in the 1970s in England, Nunn became very interested in interspecies intimacy. Nunn desired a more empathetic connection with this tiny creature. His installation seeks to rebuild the potential relationships between humans and snails.

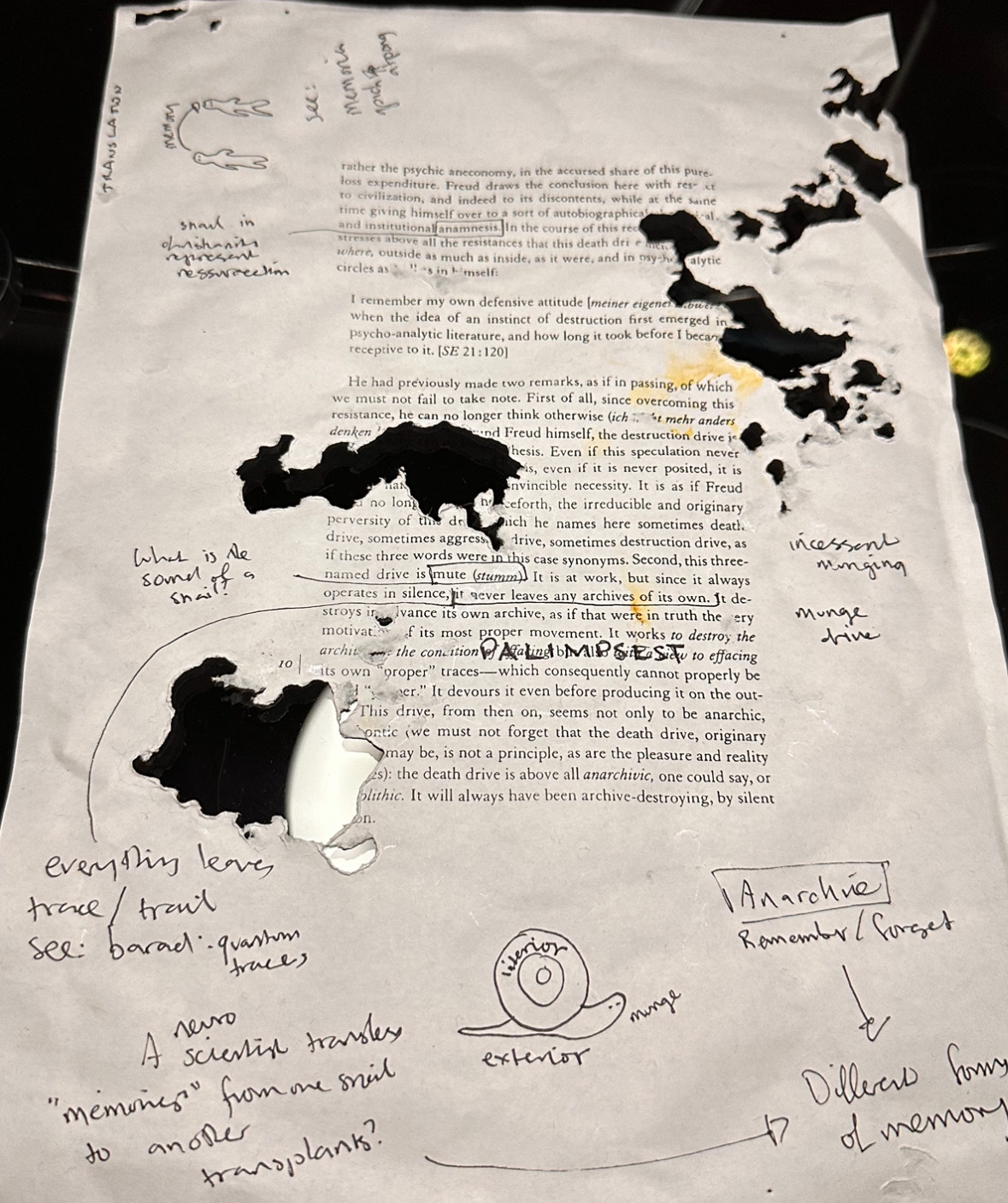

Resting on a table, Nunn offers a snail-chewed page of Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression by Jacques Derrida and Eric Prenowitz, indicating Nunn’s interest in the “anarchive”–what is missing from the archive. Nunn imagines the snail and its wet body as an anarchive. No one knows what goes on in the snail’s house, where the slug lives and carries all its mystery. Nunn envisions a fictional “snail man” who gives himself to his snails and becomes one with them, attempting to understand their ways.

On floor-level, at a snail’s eye-level, I noticed I munged it all up (2023), a video display that Nunn had placed there. Here, Nunn mimics the behaviours and psyche of a snail, “munging” the archive. “Munging” is a term derived from the French “manger”, meaning to engage something by chewing it like an animal. We watch as the artist eats the whole archive of newspaper articles about snail racing. Spitting them out to form small statues out of the wet mush. The artist is making a new archive: the archive of a fictional, anti-social man who lives with hundreds of snails. When I spoke with the artist, he told me that he was seeking a snail-like approach to archival engagement.

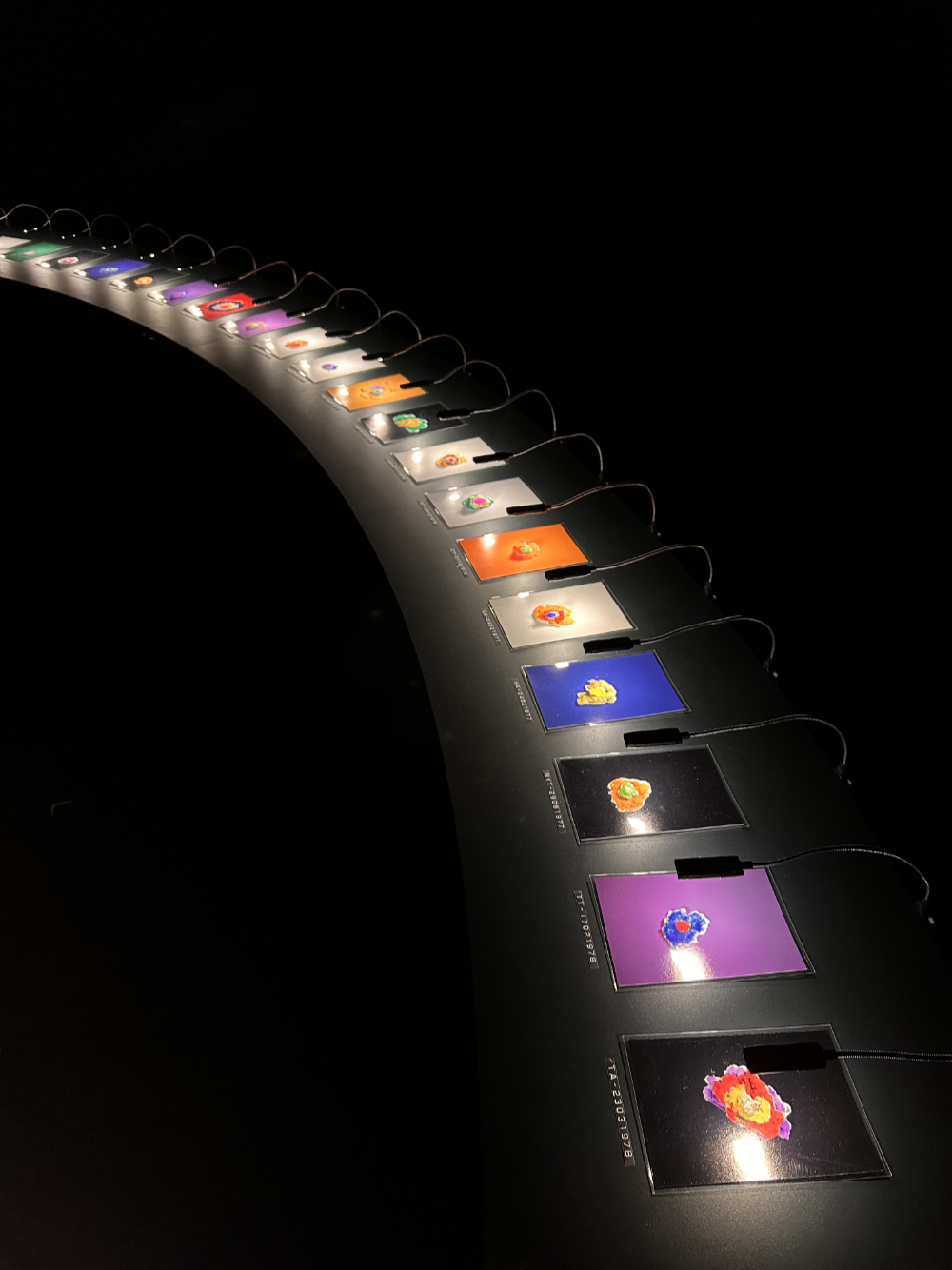

One of the most striking parts of Nunn’s display is 24 colourful archival prints lining a curved display bench, which form a tribute to Henri Matisse’s L’Escargot (1953). Nunn discovered that snails do not digest pigment if they eat coloured paper, they just leave vibrantly coloured trails. He wondered if Matisse had witnessed this curious snail phenomenon during his later years when he made L’Escargot.

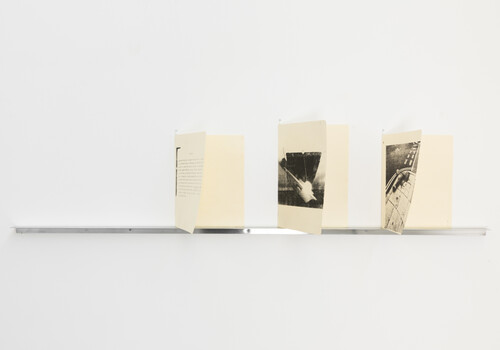

Nunn’s installation is laid out to reflect the spiral snail’s shell, while also articulating snail-like movement. In a different part of the VCA grad show, Honours Department, artist Rochelle Morris’s Plant-bombing (2023) uses natural materials to create a marshy, forest-like habitat, which is closer to the terrain that a snail may prefer. By contrast, Nunn’s display is exceedingly clean and crisp. Such a choice forms a performative response to archival study, offering a thoughtful, composed environment amid the chaotic and incomplete nature of archival material.

Altogether, Nunn’s installation, which incorporates generated chat, video, audio, digital prints and more, appears like a space-age diorama of orbiting planets and galaxies. In this big universe, the snail is such a tiny species that sticks to terrestrial nature, enjoying a perfect nearness. After all, the snail kisses the soil with its whole body, embracing it intimately with its entire being.

Sirui Yang is an emerging mixed media creative practitioner, writer and emerging art manager. She is continuing to evoke her unique feelings of vitality in nature through multidisciplinary practice.