Bachelor of Fine Art (Honours), MADA

By Fern Cook

Naarm, late November. The weather is soupy. Allergens drift along the gutters. Laneway jasmine plants slowly rot. Long dusks follow you home. Around the city, blocks of art studios are patched, painted and—painstakingly—emptied, so that a brief, intoxicating event may take place: the university grad show.

On each of the days that I visit Monash’s show, I am faced with a fraught sky and tepid wind that has become familiar. These sticky days are troubling to the senses. A consciousness of my own form arises—of its surface and reactions. I pick at this feeling throughout the exhibition, becoming stuck in and around works whose relationship to the body is likewise complicated.

Annie Wallwork’s Tere (2023) seems to understand the damp feeling well. The room that holds the Honours student’s series is compact—each work doused in the glare of an overcast light coming in through the window. The minutes melt as I stare into the abyss-like fold of Interior Crack (2023), a framed piece that rests diagonally on the floor and whose jagged central crease conjures bathroom ceilings, earth fissures, an upturned palm. Though I am sure the soft distortions of a work like Rising Damp (2023) reflect mould or decay, the longer I look the more I become convinced of its corporeality. I see a face, a scratch, an imprint of bone. I am drawn to Wallwork’s process for the residues it creates, then obfuscates. She captures an uneasy interaction between body and environment. Intricate textures have become embedded in sheets of paper through a process of graphite rubbing. Pseudo-metallic surfaces bend and warp in response, in some places to the point of rupture.

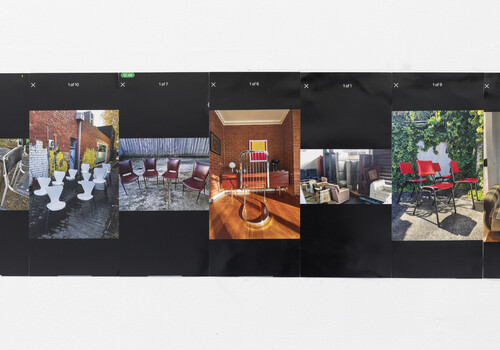

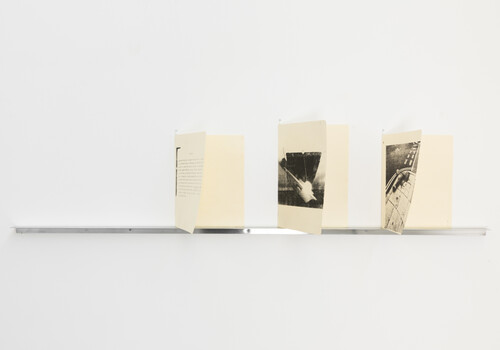

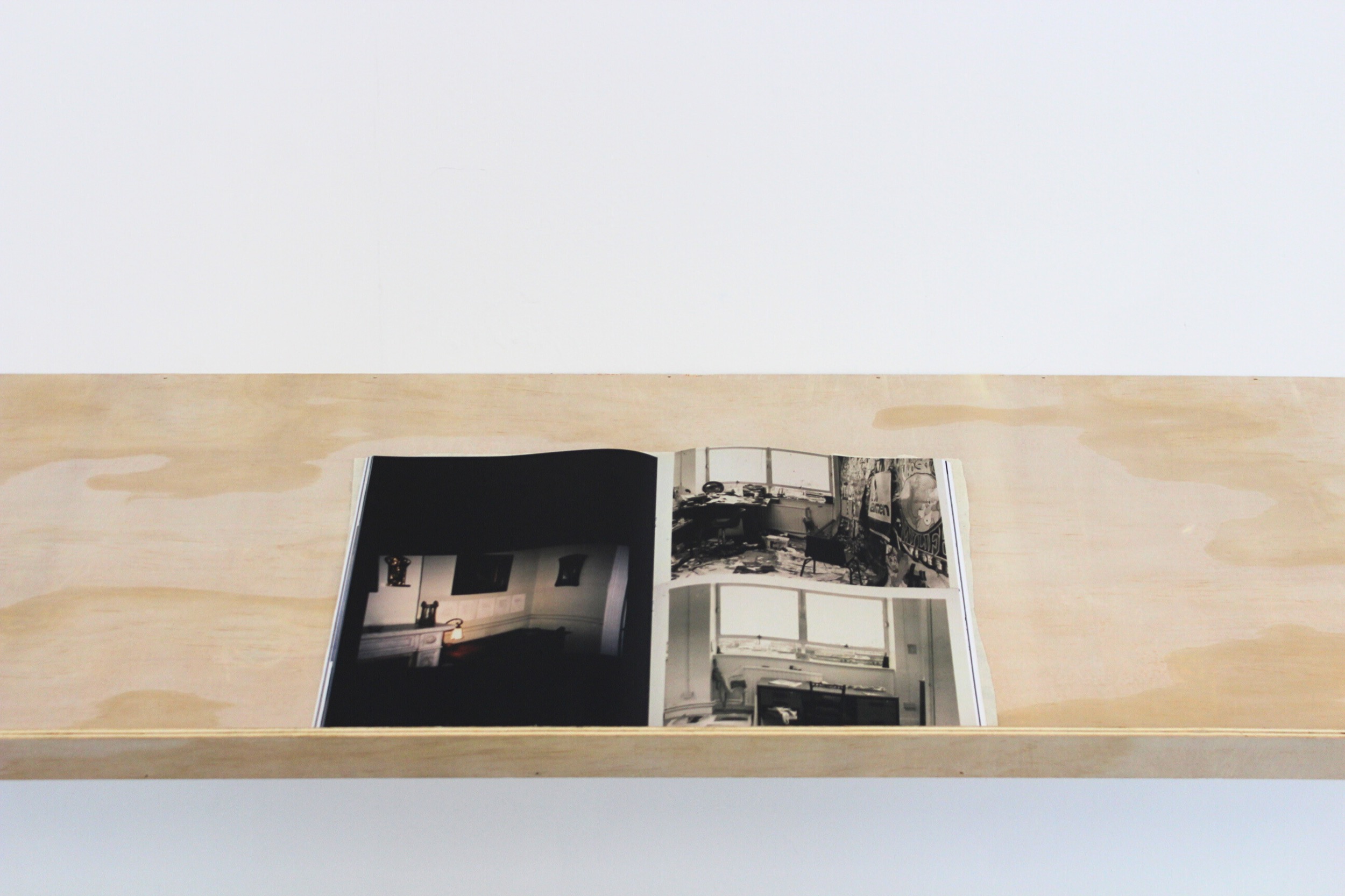

Upstairs, I linger over the glossed pages of I think early on everyone has a reason for (2023), the work of third year art history and curating student Camille Hassan. The bound form has a page that insists on falling open, where two photographs stand out. A studio desk is shown in extreme iterations of chaos and order. One cluttered, one clean—almost beyond recognition. A creative and cathartic process is reflected in the physical space, a trace of an artist at work. Hassan’s cloth-bound publication is a curated archive drawing upon the life and practice of her late mother, the artist Kate Daw. Here, Daw’s oeuvre manifests in photographs, letters, ephemera, and works dating back to her own student years. Hassan’s voice is a consistent thread throughout, a tether that situates the granular, non-chronological account in the present moment. Documenting a way of seeing, Hassan also gestures at “art’s capability to live on.” A creative form of biography, this tender, intergenerational portrait of the obsessions, spaces, and rituals that inform an artist’s life acknowledges the richness of speaking to the archive—of addressing it personally.

To encounter curator Jennifer Hunt’s Honours exhibition unearthing our requiem is to become ensnared in a web. A trail of footprints, the spectre of a hand, distorted angels, and strands of synthetic hair encircle the viewer’s body. I find myself looping, watching my step. In this project, Hunt acts as a conduit for the practices of artists Iona Mackenzie and Annie Wallwork, contemplating the purgatorial energies present in the practice of exhibition-making. She tests and questions the role of the curator in leveraging this power, a cerebral premise upheld by a suite of works that are visceral.

Mackenzie and Wallwork’s pieces are alternatingly abject and mythical, creating a macabre encounter. Mackenzie’s how his feet formed shallow craters in the muddy ground (2023) returns my bewildered gaze from its place on the wall. Layers of plaster, papier-mâché, and clay swirl into a pearlescent form. A rounded crater dips inwards, leaving an impression mark. Is that a reptilian eye gazing out from its centre? It follows me around the room. In Wired 1 and Wired 2 (2022), Wallwork entwines hair, chicken wire and muslin, emulating a deconstructed snakeskin texture that is both decorative and grotesque. I am thinking of my shower drain and its hairy concoctions. Beneath these works, the emerald surface of Reflections (2022) looks up from the floor. A skeletal hand reaches across the painting, emerging from the slick pond. Scum accumulates in two transparent bricks resting on top of each other in Wallwork’s Ash Foundation (2023), a work hidden in a stairwell nook. The flimsy bodies of insects are mired in resin. I think of itchy bites and sweaty weather. There is an outside world to get back to. I descend the stairs.

Fern is an artist, writer and arts worker living in Naarm.