Master of Architecture, RMIT

By Safa El Samad

Descending into RMIT’s Design Hub Gallery, my first impression was, “is that it?” The gallery, shrouded in dim lighting, was lined with rows of uniformly sized panels, each approximately 900 by 1800 millimetres, evenly spaced across every wall. As an architecture student from Monash University, preparing our end of semester exhibition was a weeks-long affair involving intricate planning and execution. Why weren’t RMIT students also tasked with becoming temporary exhibition designers?

As I spent more time in the gallery, I realised the effectiveness of RMIT’s approach. This seemingly ubiquitous method of presentation not only brought the focus on the work itself but also ensured equitable space for each student to showcase their projects. Closer inspection revealed a nuanced aspect of these displays—what I would describe as a multiple narrative image. Two distinct sets of drawings are conveyed within each panel. In lieu of a plain background, a digital set design is constructed, which appears in the form of offices, studios, cabinets, and even an arcade machine. These set designs are used as the backdrop for students to present their projects in the form of architectural drawings, models, and renders. Within the confines of a single panel, these students created entire worlds without the need for an elaborate physical exhibition design.

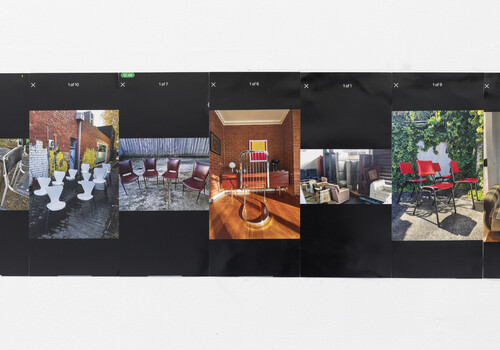

Take the work of Darcy MacCuspie titled Keep it Real. His project critiques the limited influence of architects in projects driven by economic interests and proposes a counterfactual project in Geelong, using architecture as a tool to redefine property and space autonomously. In this project, the viewer is immersed in a portable office, an atmosphere created by folding tables and chairs, and cardboard boxes along the floor. The view from the window situates us on a construction site. A bookshelf with a pinboard in front cleverly doubles as a narrative element and a secondary display of MacCuspie’s architectural drawings, maps, and ideas. Other details which enhance the panel include a construction helmet, ceiling tiles with fluorescent tube light, an exit sign, a fire extinguisher, a wall clock, and my favourite detail: a framed image of the docks at night illuminated by fireworks with text beneath the photograph that reads “KEEP IT REAL”—the title of MacCuspies’ project.

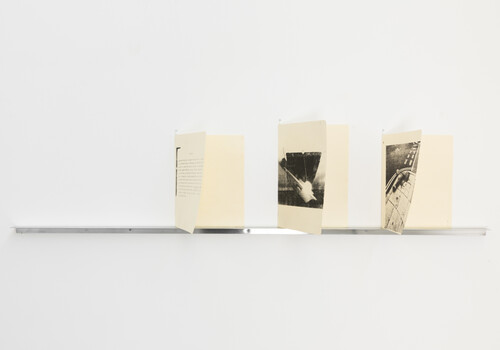

Artefacts Washed Along the Shore by Taylor Ristevski also used this visual storytelling technique of presenting multiple narratives in a single panel. Ristevski’s creation is a life-sized display cabinet, tinted in a mauve hue and adorned with decorative fish motifs, set against a backdrop of floral wallpaper and floorboards. Within this neat crevice, the glass doors stand open, and the lower drawer is extended, unveiling a unique collection of seaside artefacts. Additionally, the display features various renders and drawings that incorporate these seaside elements into the design of [The]{.underline} [Mission to Seafarers building]{.underline} in Docklands. This project delves into the theme of adaptive reuse, showcasing how 3D-scanned and altered family seaside artefacts can be integrated into urban landscapes.

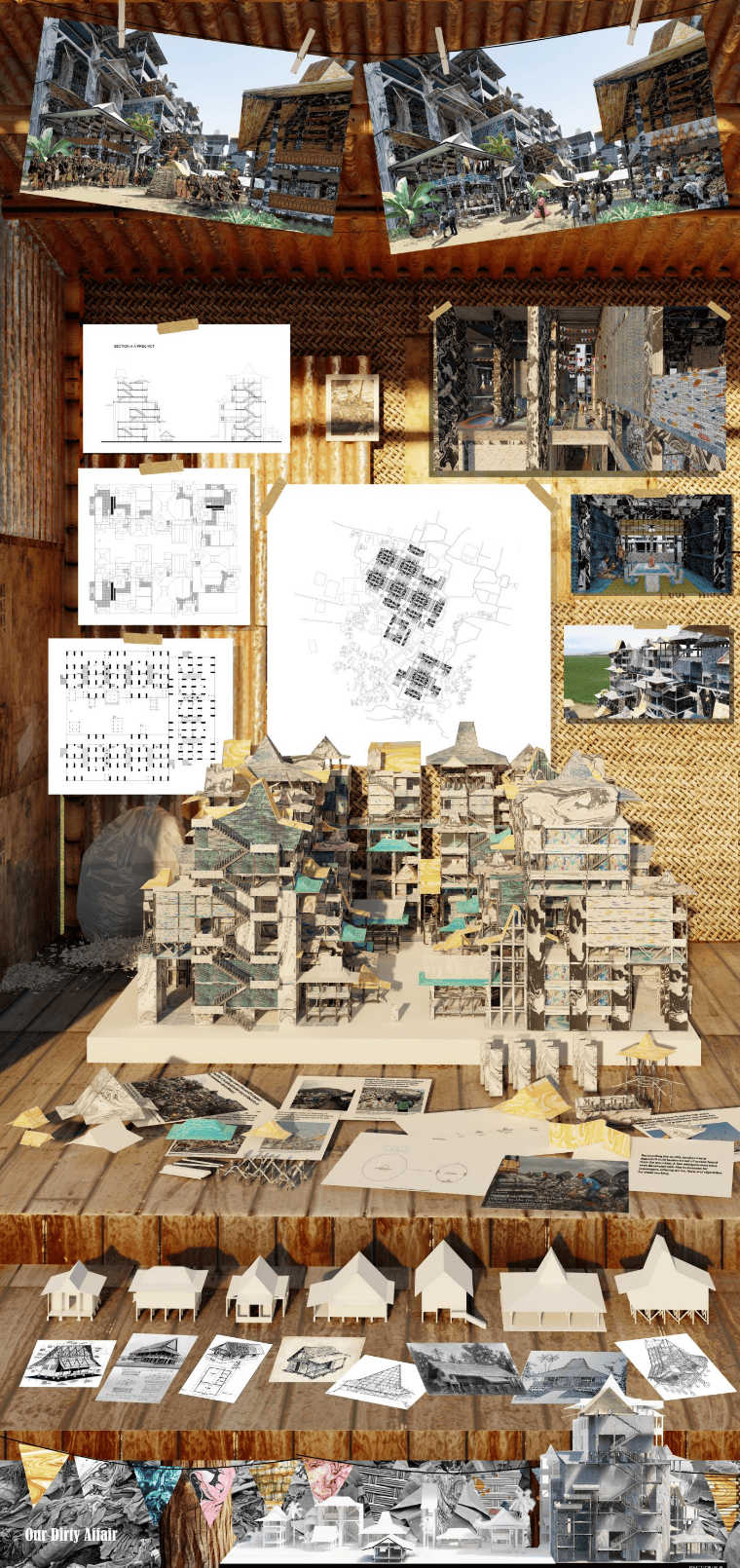

While Ristevski emphasises the narrative image, in Sherina Suhartanji’s project Our Dirty Affair, architectural drawings dominate the frame. Using a series of renders, drawings, and models in the foreground, Suhartanji communicates a project focused on Southeast Asia’s largest landfill site, “[Bantar Gebang]{.underline},” where locals and members of seven Indonesian tribes have relocated to earn a living, and reside in makeshift huts constructed from scraps found within the landfill itself. The project focuses on reimagining waste management by enabling these residents to construct their own culturally reflective homes from waste. As a backdrop for the project, Suhartanji replicates one of these huts constructed from rusty corrugated sheets and a rattan panel. In the foreground, smaller drawings are placed on a wooden deck, each drawing correlating with the models directly behind them. Positioned one step above are additional flat-laid drawings and a more prominent model situated in the centre of the panel. Above, are larger drawings adhered with sticky tape, while a couple of drawings hang from a line with pegs. Although Suhartanji showcases a larger quantity of the architectural project, and a compelling concept, the set dressing feels like a background addition rather than a cohesive framing device for the work.

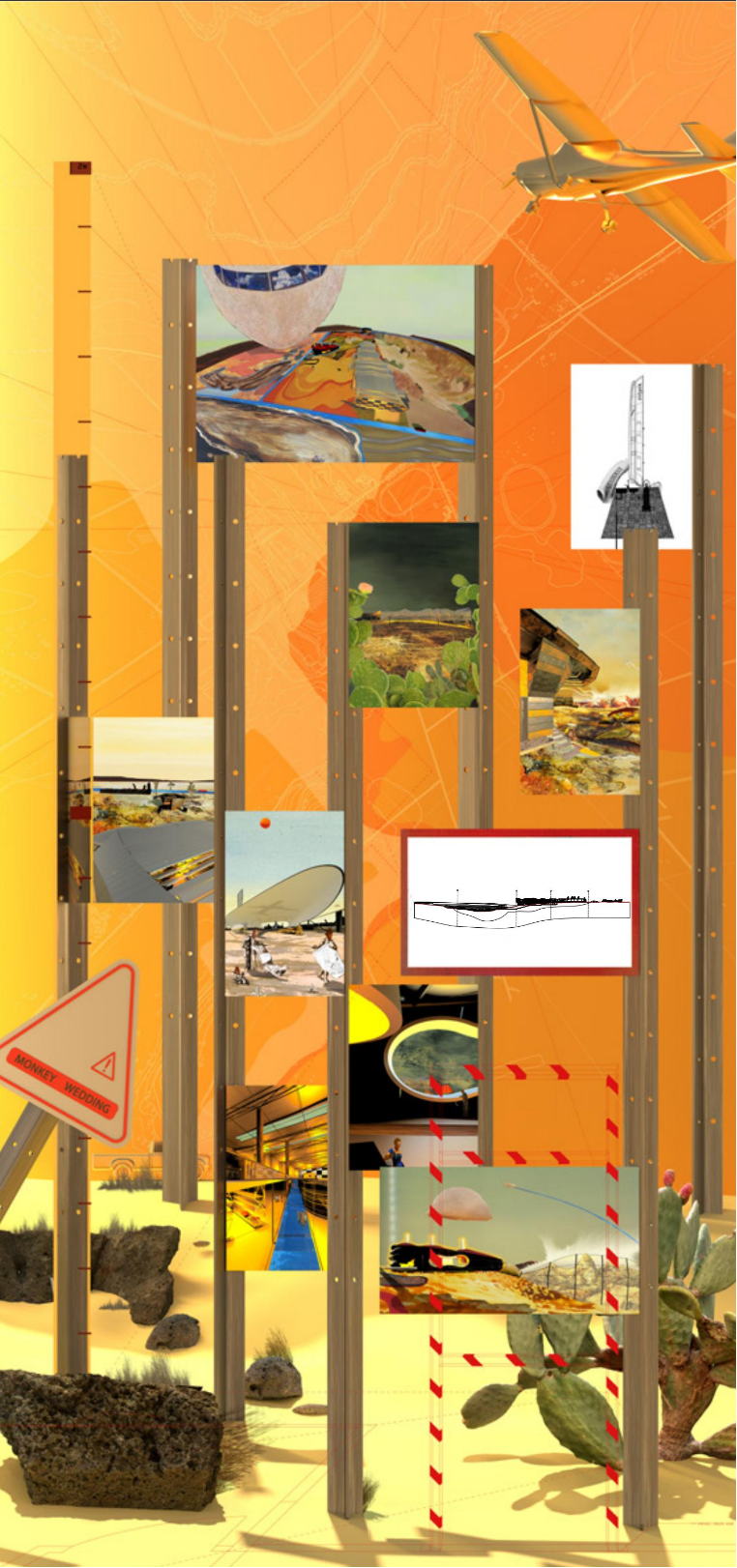

Stefan Spanopoulos’s work, titled Monkey Wedding: A View, adopts an imaginative yet more minimal approach. Spanopoulos’s project explored the relationship between a pet crematorium, a motocross track, and a landfill site. It’s an absurd concept that taps into its own strangeness to produce a compelling set of visuals. Unlike the familiar spaces of an office or display cabinet mentioned in the previous projects, the world Spanopoulos creates feels foreign. This panel was far less cluttered than others, with a vast freshness of an orange tinted sky. Rising from a sandy desert foreground, situated somewhere between Bacchus Marsh and Parwan, are various sized fence posts doubling as billboards for drawings and renders of Spanopoulos’s design proposal. The simplicity of a single-coloured background gives space to the architectural work, balancing the set dressing with technical drawings.

Finding a balance between these thesis projects while also being able to tell a narrative is not a simple feat. These projects are dense, and the summaries that accompany them are reduced to mere paragraphs. Within each student panel there can be ten, twenty, thirty, or more images that each deserving of its own wall space and text. Yet, in this limited format, these students have demonstrated the ability to distil complex ideas into potent visual stories.

Safa El Samad is a multidisciplinary artist, fashion designer and occasional writer. She is currently completing a Masters of Architecture at Monash University in Naarm/Melbourne.