Master of Architecture Design Studios, Monash Architecture

By Rachel Soebekti

The exhibition commences under the warmth of an orange canopy suspended above a line of foldable tables. Brightly coloured sticky notes are scattered across an aerial map of Clarence Valley in the Northern Rivers region of New South Wales on Bundjalung, Gumbaynggirr and Yaegl Country. Wooden stools invite you to sit down, take in the collection of thoughts, and respond to prompt cards asking “In this exhibition, I liked…” and “In this exhibition, I saw the opportunity for…”

Here, Mel Dodd, Nikhila Madabhushi, Kerry O’Neil, Robert Lees, and the nineteen students of Placemaking Clarence Valley’s design studio invite you to be a participant in the work. They ask you questions that mimic the empathetic approach to community consultation explored by the studio. Student proposals are found in the booklets placed among the scattered props on the tables. The presentation of the Master of Architecture and Master of Urban Planning and Design student work in thick booklets appears bureaucratic. While impressively consistent, it does make me wonder whether the unique perspectives of the students have been subsumed by the studio’s representation.

The raw grittiness of the exhibition spaces on level three in Building F—characterised by unpolished concrete floors, exposed ceilings and rough-sawn timber stud work—set the scene for a welcome attitude of sophisticated experimentation consistent with the thematics behind studios and projects.

Wasted, a design studio led by Frank Burridge, promotes a custodianship of landscape through the considered reuse of existing “waste” materials. The studio’s commitment to materiality is explored through a long ensemble of brick, concrete, and textile woven into the soft, red earth of the landscape. Nestled grassroots and dried gum leaves bring the atmosphere of hot, baking summers into the exhibition space. Juxtaposed against this, the playful experimentation of 1:1 playground models optimistically colours a serious conversation about climate change and material obsolescence, but there seems to be some disconnect between these objects and many of the exhibited student proposals.

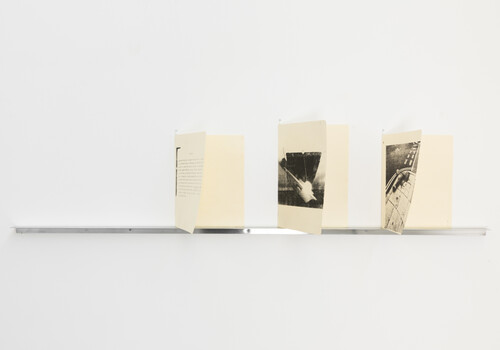

Towards the end of the corridor, you are met with the soft ambiguity of a curtained confessional space at the centre of an open studio. Anthony Clarke’s design studio Carceral Geography explores the role of architecture in relation to community re-entry after incarceration. As with other studios, such as Minus and Placemaking Clarence Valley, student work is packaged into minimal and restrained portfolios hidden within the belly of the exhibition. These booklets are used to communicate each student’s project as part of a body of research to complement a wider thematic investigation.

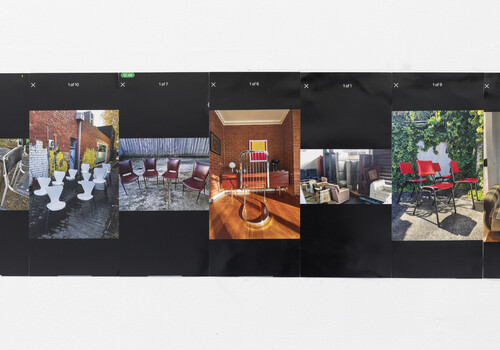

At large, Monash Architecture’s MADA Now 2023 exhibition is concise and considered. Thematics bounce from intense pragmatism to the speculative and theoretical, with enough negative space to hold the audience’s attention. This seems to be the outcome of a focus on creating a singular set that captures each design studio, respectively. However, this means student work is pushed to the fringes and often feels like a supporting act to a greater collective. In the case of Louise Wright’s design studio Minus, your first encounter with the exhibition is a pair of screens seated on office chairs playing video loops filmed by the architect and professor herself.

While there is much to commend in the way of exhibition atmosphere, one has to question if this comes at the sacrifice of student-led individuality. After all, the end-of-year exhibition is a chance for graduating students to set an agenda for their careers and plant a flag as to how they want to practise in the wider community.

This strikes a poignant nerve for wider consideration: how much should students be allowed to control their final projects? Or, in the context of Eduardo Kairuz’s design studio titled Fugitivity, where students donated the exhibition budget to various global crises, and invite you as the audience to do the same through neatly located QR code, is training a cohort of active social participants the change we need to see in architecture?

Rachel Soebekti has recently completed a Masters of Architecture from The University of Melbourne.