Master of Architecture Design Studios, Melbourne School of Design

By Madeline Lo-Booth

As a student architect, it’s unlikely that any building you design will be constructed anytime soon, if at all. The end-of-year exhibition is the only real opportunity to prove your skills and express your ideas. At the Melbourne School of Design, these exhibitions have all the pageantry of a job fair, with student work accompanied by QR codes linking to online CVs or physical business cards and folios displayed on acrylic document holders.

It raises the question: Who is the audience of a student architecture exhibition? Is it other architecture students? Teaching staff? Industry professionals? Parents?

Could an exhibition like MSDx Summer 2023 ever be for a general audience? And does this apparent gap—between architecture students and the public—speak to a greater decline of the architect in public life today?

The volume of work in the Dulux Gallery and foyer of the Glyn Davis Building is incredible. Temporary walls covered in vertical strips summarising students’ independent thesis projects dissect the space into smaller galleries grouped by supervisor.

There is enough work on display to console parents after years of late nights and extensive investments in printing, model materials, and computer software. It also signals to potential employers that this cohort is certainly capable and ready to enter the workforce.

The display panels, however, are overwhelming. The near-uniform layouts comprising “hero” render, plans, sections, perspectives, and text suppress a sense of individuality between projects. Furthermore, the abundance of work contained in such a limited space isolates the layperson from engaging with the work, or sometimes even knowing where to look.

Nonetheless, moments of originality announce themselves confidently. Ione Cardoso’s thesis project incorporates hand-drawn watercolour perspectives reminiscent of botanical illustrations, and Mengping (Vicky) Huo’s lively axonometric section depicts a housing development for social recluses (hikikomori) on a horizontal scroll laid across a bench.

On the upper floors, the Masters studios are displayed in classrooms and hallways. Design Studio E 10 Offcuts, headed by William Cassell, presents a range of impressive models crafted from construction waste, displayed at knee-height atop cinder blocks, including work by Yeuk Kei (Stephanie) Chow, whose corresponding 1:50 and 1:1 scale models are executed with precision. There is an abstract beauty in the 1:1 scale models, which offer a fragment of students’ building proposals. But they are hard to appreciate when densely packed into one half of a classroom. It’s a reminder that architecture is not immune to real estate—and certain areas of the Glyn Davis Building sure are hot property.

The bottom floor of the Hansen Yuncken Suspended Studios, a space already impressive for its unusual hanging structure, is home to Design Studio E 04 – Spatial Gastronomies, led by Yui Uchimura.

Yellow cellophane strips cover the light tubes on the ceiling to render the room sallow. A neat row of material samples and models is presented on tables (some with tablecloths, others inexplicably without). Plans pinned to the wall depict propositions that consider the lifespan of ingredients from production to presentation, with design schemes for restaurants in domestic settings. This exhibit was awarded “Best Overall Exhibit.” It’s full of solid student work, with especially strong models, but it does make you wonder whether the space allotted elevates an exhibition’s reception.

Donald Bates and Anna Nervegna’s Design Studio B, part of the three-hundred-point Masters program, presents A3 sheets Blu Tacked to the red Lovell Chen Lounge area. Accompanying models on the central table make for a solid sight—but are we admiring a piece of architecture, its representations, or the exhibition?

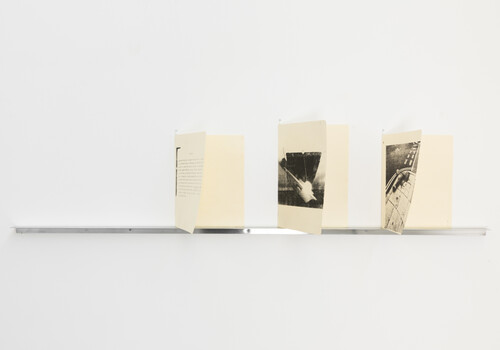

Design Studio D 01 – Just a house, an apartment … and maybe even some units, has a unified approach with booklets produced by groups of students and models sprawled across an offset rectangle crafted from butcher’s paper.

Led by Colby Vexler, trios of students propose minimal adjustments to suburban homes, signalled by orange pencil on fine line-weight plans. They are presented alongside renders that use overcast skies to recreate the washed-out photography style of Rory Gardiner. These images occupy the perimeter of the space on what are usually work benches.

Particularly strong are the renders and the accompanying model produced by Jiaji Shi, Yume Ebihara, and Yushan Shen, which exemplify the restrained style the studio aims for.

A vase and paper lamp help to convert the locker area into a homely space. These objects are likely to draw in the everyday person, perhaps someone who has watched the latest season of The Block and is now aware of the “Japandi” aesthetic pushed by Steph and Gian on the show.

At the same time, these seemingly random accoutrements are likely to be the exact thing someone with an intimate appreciation for the work of Isamu Noguchi might cringe at—mass-produced versions of design icons.

This tension precisely captures the exhibition, and the quandary of architecture today—who is its audience?

Madeline Lo-Booth is a writer from Naarm/Melbourne.